KR Meera: The Verdict

KR MEERA’S FICTION plays witness to the world. It is strongly political, at diverse levels of themes and narration. Her work interrogates patriarchal norms that subjugate women; hard-hitting subjects mirroring contemporary life is her canvas.

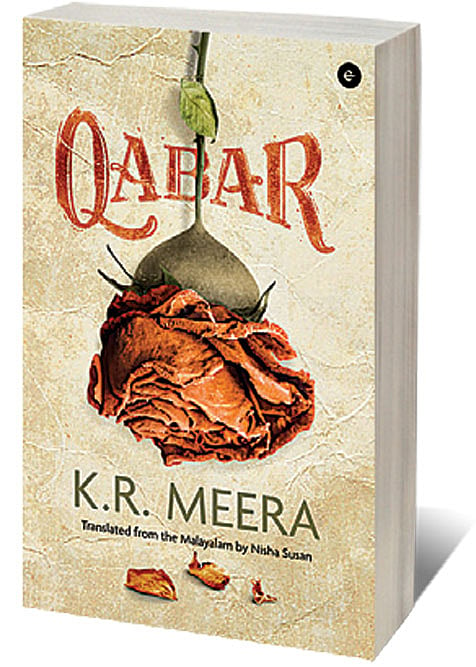

Meera’s latest novella Qabar, published in Malayalam in 2020, and now translated into the English, opens myriad questions on law, land and patriarchy, as practiced in the country. The opening line hints at what lies ahead, “The demolition of his ancestor’s qabar—that was what his civil suit was about,” but the narrative is not just about a lawsuit. It’s equally about the ceaseless power politics of gender privilege, about destructive attitudes embedded deep within matrimony. All this is etched in about 110 pages, the narrative paces furiously between past and present, fantasy and reality, and connects a number of storylines.

As the foundations are laid for a temple to rise on the site of Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, Bhavana Sachidanandan, an additional district judge around whose life and work Qabar commences and concludes, is flanked by a male protagonist duo; the petitioner in the case, the architect Kaakkasseri Khayaluddin Thangal and Bhavana’s ancestor Yogishwaran Ammavan, both men of the occult. The novelist uses their sorcery to weave magic realism into our reading experience.

In Qabar, there is this incredible character, one of those invisible working women, ceaselessly ploughing through her household duties round the clock, stoic about an unequal marriage, and commuting four hours daily to work and back. Yet, she is a voracious reader. “Sitting when I had a seat. Standing when I didn’t have one. That’s how I read all that I read.” When we meet her the first time, she is reading the South Korean writer Han Kang. She teases her daughter, “With this judge job of yours, you have no time to read novels. I suppose.”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The strongest woman in the book, the mother, curiously, is nameless. Yet, it’s she who has the most quotable lines. She justifies starting her life anew after retirement with a canine family, with the line, “Love isn’t a service charge. It is a sense of completeness that one finds in another person.” She once tells her daughter, “When I was your age, I thought family was heaven. After a while, I understood that this too is a workplace.” When Bhavana approaches her after a failed marriage, she quotes Tagore to her; how a bird has a perch in the cage but no space there to spread her wings.

Reality can often limit a woman’s experience and dreams. Meera has therefore created a fantasy space in which exists that rare breed. Thangal is the man who listens to and respects women, he can and does read their minds, and he sends the fragrance of the Edward rose into their shared spaces. It’s the patriarchal man who is portrayed in Qabar as the weak link, insecure at the loss of privileges he was born into.

Qabar holds a mirror to contemporary Kerala, busting the myth of liberty and democracy in the life of the educated Keralan woman. The parallel narratives—the need for the birth of the scholar Brahmin, the camouflaged story of the death of the ancestor with occult powers, the two young divine girls who merge into one like vanishing twins—seamlessly woven into the story fabric create the layers that hold the story intact.

There are a number of questions thrown at the reader. Is the family the qabar (grave) here, where the woman buries her dreams and her identity after marriage? Is justice buried for want of proof? Or is it the attitudes in our minds that we wish to conserve in coffins? The writer leaves only hints. The reader anxiously hunts out other inquiries. The discerning reader hears a clarion call to rise above the ordinary and find the questions first. The resolutions are perhaps not in our hands. How can one deal with such beauty and craft? Perhaps only by reading it again and again.