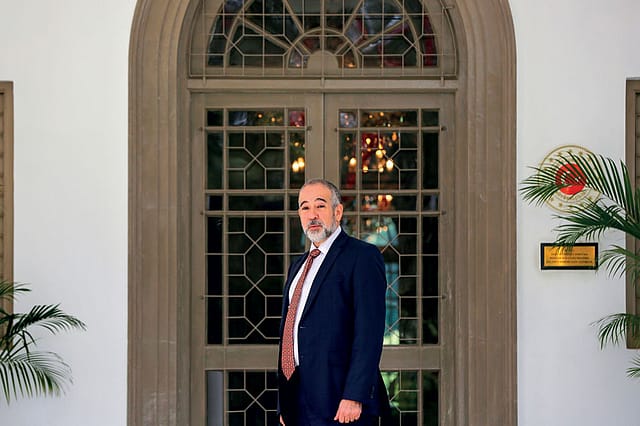

‘The trauma of forced migration is in our genes,’ says Firat Sunel

THERE MAY OR may not be any solidarity among victims but trauma changes people and nations—and it doesn’t go away. For the Republic of Türkiye, or Turkey, loss of empire, the war with Greece and exchange of population, and the post-Ottoman national reinvention, all of it through a decade (1911-22) of continuous conflict, had hardly receded into the past when another global conflagration landed on its shores. President İsmet İnönü’s diplomatic balancing between the Allies and the Axis kept the young republic out of World War II till near the very end in February 1945. What it could not preclude was the suffering of the Turkish people.

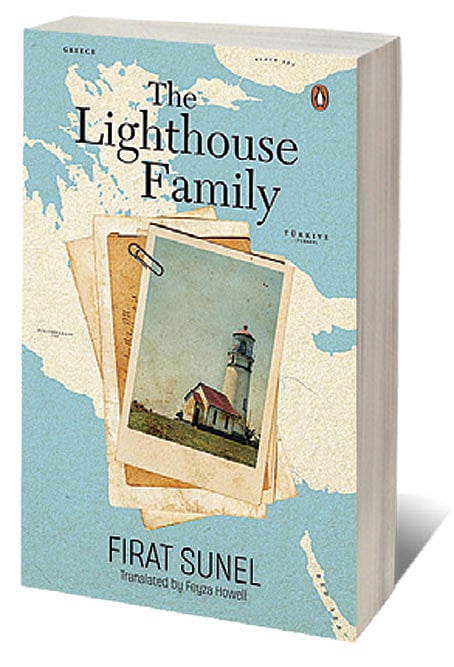

The Lighthouse Family (translated by Feyza Howell; Penguin; 178 pages; ₹399), the third novel by Firat Sunel, ambassador of the Republic of Türkiye to India, begins in the summer of 1942 “somewhere the world forgot, somewhere fated for desolation.” That somewhere is the village of Sarpıncık on the Karaburun Peninsula near İzmir and its isolated lighthouse, the Sarpıncık Feneri, clinging to the hills jutting into the Aegean Sea, facing the Greek islands of Chios in one direction and Lesbos in another. This desolate place, “far from everything, everyone, and everywhere,” as Sunel tells Open, is the backdrop for the coming-of-age of the unnamed protagonist whose family of father, mother, paternal aunt (Hanım Hala), and three siblings (sister Feriha, the eldest; brother İlyas, the middle child; and the narrator) live in a small house next to the lighthouse the father had helped build and of which he is the keeper. “None of us knew it then: isolation and poverty may have been our fate, yet that final period of our childhood was the best time of our lives,” recalls the narrator of the summer of 1942, the last time they are together as a family.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The trigger for the telling of the tale is a lost photograph the narrator discovers in a flea market in a German coastal town in the 1980s. This photograph—taken by a mysterious European, possibly a German agent; “or even Dutch,” as Sunel warns, who had appeared at Sarpıncık Feneri in 1942—“is the only frame where my whole family are present,” says the narrator. “That little kid in the front, the one in shorts giving a military salute: that’s me… Blissfully unaware that a military junta would later change my life… Dad’s hands on my shoulders, like he wanted to restrain me… Mum to his right, silent and docile as ever… the grim-faced woman sitting in a chair bang in the middle is our hanım hala, madam paternal aunt… My big brother İlyas to her right. Two years my senior, but we look like we’re the same age. He seemed to be growing younger as I grew up; I always thought we’d end up the same age one day. Which is not what happened… Standing next to me in a patched pair of trousers… is my big sister Feriha… The wildest of us all, obstinate and a daredevil bold enough to stand up to our dad. She lived in a world I could never enter, probably because I was a child… I never told her; but she was pretty, despite the shabby clothes and the short hair she had cut herself…” (Sunel happens to be an amateur photographer and had taken the photograph of the actual Sarpıncık lighthouse featured on the Turkish cover.)

“The lighthouse is not just a venue or a building. It symbolises loneliness and desolation. It is in a very, very remote area. That’s why the three siblings have no one else to play with, they are playmates and also best friends. And that’s why I emphasise their unwavering sibling bond. They are so isolated in this lighthouse that even Feriha doesn’t understand that she’s a young woman. She thinks she’s like her brothers,” says Sunel, echoing the words of the narrator: “We always wore the same things; utterly unaware that she was a young maiden, she wandered around barefoot in summer and winter in a pair of long trousers with patched knees and an elasticated waist… It’s not as if we’d feel self-conscious before anyone—so rarely did we have company.” It wasn’t an idyll but there was plenty of the idyllic: swimming in the sea in summer, watching the Chios-Lesbos ferry as its captain (a Greek who grew up in the now abandoned town of Sazak nearby in Karaburun) hooted in acknowledgement of the children watching the ship from the lighthouse, spending nights up on the lighthouse gallery. Not even the hard work on the land could spoil such pleasures. It lasts till war tears apart their little world. The ferry stops, the Chios lighthouse opposite goes dark, and one night the Germans light up the sky with their bombs as they destroy Lesbos. Turkey would remain at risk of being pulled in. Rationing coupled with the men being called up meant little to eat, a predicament that doesn’t befall the lighthouse family till later, protected by its isolation as it was.

If war comes to the Aegean as an intruder, the lighthouse family is already marked by a past scripted by realpolitik and the determinism of history. The father and his aunt are immigrants from Chios where their family, like millions of Turks in Ottoman Greece, had lived for generations. The mother and maternal grandmother, living in Sarpıncık village, hailed from the predominantly Greek town of Sazak, abandoned when the Rums (from Roman, as the Greek population of Anatolia and European Turkey were called) were forced to leave just about 20 years ago. The Treaty of Lausanne (January 1923), to which is attributed the largest mutual expulsion or exchange of population in history, merely concluded a process that had begun before World War I with the massacres. This uprooting and loss of home for Greeks and Turks “had a big impact on the demography of Anatolia,” says Sunel. “The psychological impact was huge. I wanted to write about this in a humanistic way. Take the father, he hates the Greeks (‘It never occurred to us then that one day we’d be kicked out of the island, cram into boats to seek refuge on the shores opposite, leaving everything we owned behind… Whoever is living in our home in the inner keep now: may he never enjoy it!’). The trauma is there in him, it hasn’t gone away. But Hanım Hala is more mature (‘On the day we left the island for good, many of our neighbours came to see us off, their hands and arms full of baskets and sacks of provisions.’). Such events are always traumatic, not just for the people forced to leave but also for those left behind. Everybody living in Türkiye and Greece had to suffer. I’m not criticising the decision [of exchanging the populations] but that was the reality.” Sunel knows it only too well: “The trauma of migration, and forced migration, is in our genes. My grandfather and grandmother came from the Greek mainland and Bulgaria. They settled in Türkiye. Then, when I was five, my parents went to Germany as Gastarbeiter (guest workers). That was a new immigration for me. As if that weren’t enough, I have chosen an occupation where I settled all over the world. It’s a tradition I’m following (laughs) and we diplomats are the nomads of the modern world.”

It’s at the lighthouse that Hanım Hala, Sunel’s “symbol of wisdom”, finally plants the mastic tree she has carried around in a wooden barrel, grown from a twig she had snapped off the tree in their courtyard in Chios, knowing instinctively that the lighthouse is where her journey would end. The transplanted mastic tree, which doesn’t bleed till tragedy hits the family, is more than a memory. It’s the tangible line of continuity just like Hanım Hala. She never recovers from the death of İlyas, of a heart of gold and brittle bones, the weak sibling who reads the narrator’s textbooks by day (while he works the fields with Feriha) and passes on the lessons to his brother by night. But İlyas dies in an avoidable accident, falling down a slope while helping carry gas tanks for the lighthouse which had been held up by the logistical disruption.

If İlyas’ death ends the summer, at the heart of the narrative is the figure of Feriha. When a Greek war refugee named Elias washes up in the cave below the lighthouse, she helps hide and feed him. Feriha, who had answered their father’s dismissal of her as incapable of running the lighthouse because she was a girl by shouting that she knew how, would indeed become the lighthouse keeper— the very last. But helpless Elias is competition for her affection and in a child’s ignorance the narrator commits an act of betrayal that will haunt him for the rest of his life. The same ignorance that made him retort “How would I know!” when she asked him if he thought she was beautiful. “Her love [for her brother] hasn’t changed but her condition later is indeed pathetic. She is the core of the story. We don’t know if her feelings for Elias were the result of attraction or because she saw in Elias her brother İlyas. Even when she puts on the flowered dress for Elias, we don’t know whether it’s because she likes him or because İlyas liked her to wear it. Some readers said that she finally realises she’s a young woman and falls in love. But we don’t know if it’s love. And yet, the affection is very strong,” contends Sunel.

Guilt, however, doesn’t put the narrator beyond redemption. Political rebel, writer and survivor, he flees Turkey after the coup of September 1980 with Feriha’s help in a little boat over the Aegean, just as his father had sent Elias to his likely death. One of the Heimatlos (homeless exile) in Germany, he finds Delphina, who turns out to be the 12-year-old scared girl in her grandfather’s barber shop in Istanbul, both of whom the narrator had saved during the anti-Greek riots of September 1955. Chance is a risky instrument in a novel, unless cleverly used, and twice it proves a turning point in the narrative—meeting Delphina and finding the photograph. His dead father might have been mortified when he marries a Rum but Delphina is not the fleeting vision of the face of innocence in Fellini. She saves him, even embarking on a tour of lighthouse towns when she comes to share his obsession. Feriha preserves the souvenirs and gifts her brother sends her, but by the time he finally comes home after being cleared of all charges, it is too late.

“Once I was travelling by car in a desolate place and saw a sign that said ‘Sarpıncık Feneri’, the lighthouse. No one knew about it, there was no road, and I just walked. The location was so far from everything, I thought this could be a great story, or not,” says Sunel. He met the last keeper of the lighthouse who was then 85 but had a very clear memory. He was the keeper for 28 of the 60 years he had lived in the lighthouse: “He explained it all to me—not only how to operate a lighthouse (today it’s all automated) but also what happened during the war, how they lived, what they ate, and so on. When I visited 10 years ago, there was no one there. But today you’ll see tens of cars and tourists taking selfies.”

India, of course, has had the good fortune of hosting one of the greatest diplomat-poets in Octavio Paz. “Diplomats like writing,” says Sunel, “but writing fiction is rare for them, and in Türkiye it’s rarer than it is in India. But with non-fiction you get only a readership of the interested. With a novel, you reach a wider audience.” What about India (incidentally, his works have been translated into Tamil, Malayalam and Kannada)? “I have plans to write about India. It’s such a colourful country that really feeds my soul. But it will be a novel with a human at the centre of it.”

It’s the very interconnectedness of war that produces the solidarity of sufferers. Barely 20 years since they fought a war, fleeing Greeks, mostly those with roots in Anatolia, would find refuge in Turkey even as it sent aid to Nazi-occupied Greece. The story of SS Kurtuluş that sank in the Sea of Marmara in February 1942 is not fiction. Sunel insists, “When I was at university in Germany, my best friends were Greeks. We were like brothers!”