The Seat of Power

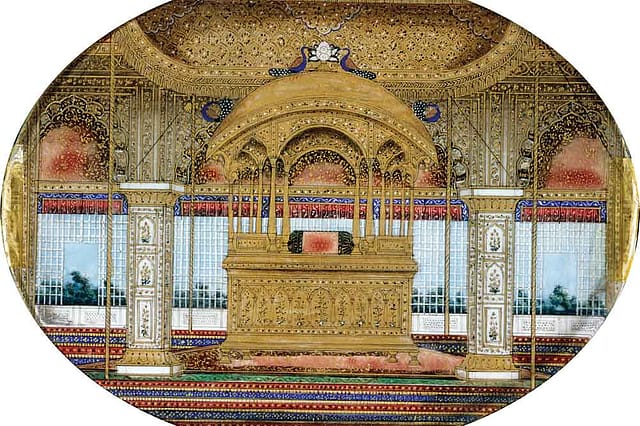

IT IS THE 18TH of April 1648, twenty years into the reign of Emperor Shah Jahan or ‘The King of the World’. The Emperor has just arrived at the Red Fort, to the newly built capital city Shahjahanabad. His is a divinely illuminated kingship that will herald a golden age for the Mughal Empire. The King enters the Diwan-e-Khaas, the Hall of Private Audiences, to ascend the Peacock Throne. Built in the likeness of Solomon’s throne, and perhaps to imbue this Emperor with powers akin to those of the mythical King, the dazzling seat with its sparkling trees and birds, finds its place in this magnificent room of walls and ceilings inlaid with fine stones, gilded silver, and gold.

This was not the first time that Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan had sat on the Takht-i-Ta’us or Jewelled Throne—as the Peacock Throne was initially called. Seven years into his reign, in 1635, he had consecrated the dazzling throne in a splendid ceremony in his other capital, Agra. It is said that the Peacock Throne took seven years to build at purportedly twice the cost of the Taj Mahal, that it had ‘a confusion of diamonds, as well as other jewels’, among them the infamous Kohinoor Diamond, the Timur Ruby and the Samarian Spinel. Most importantly, it was believed that it granted power, grandeur and spiritual authority to the succession of Mughal kings who ruled from it. Miniature paintings of the time—as much documentation as art form— depict spectacles of glory and supremacy.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Subsequent reigns, weakened by years of political intrigue and military instability, saw Nadir Shah of Persia attack the crumbling Mughal Empire in 1739 and the city of Delhi plundered by his marauding army. Legend has it that the takings from the city and its treasury, among them the fabled Peacock Throne, were whisked away to Persia. Once again, much like it had for the Mughals, the throne become symbolic of imperial privilege and prerogative, granting he who assumed it, great power. In 1747, Nadir Shah was assassinated. The Peacock Throne was taken apart; each part became its own treasured object. The most renowned—the Kohinoor diamond—has had its own colourful history; travelling to Lahore where it was briefly amongst Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s treasures, until it became part of the Commonwealth’s Crown jewels in the mid-19th century.

Historians are reliant on inconsistent accounts to stitch together narratives that speak of one, two, or twenty-four peacocks on the original Peacock Throne; of value ranging from one to four to twelve crores of rupees; of Mughal goldsmiths, Persian poets and calligraphers, and of French or English jewellers credited with design. For all the many inconsistencies in paintings and records, the allure, the aura, and power of the throne have endured. By the late 18th century, the Mughal Empire had shrunk significantly from its glory in the 1600s, where it stretched over a large part of a heterogenous continent, to very little beyond the capital of Delhi; the Emperor Shah Alam II, was, as recorded by a British official towards the end of the emperor’s reign, “…the descendant of the great Akbar, and the victorious Aurangzeb, was found an object of pity, blinded and aged, stripped of authority, and reduced to poverty, seated under a small tattered canopy, the fragment of regal state, and the mockery of human pride”. Yet, in portraits of Shah Alam II, we find him seated on the gilded and bejewelled structure of a re-created Peacock Throne—a simulacrum with exiguous regard for the reality that existed outside the frame of the image.

OBJECTS, IMAGES AND tales have long been used to capture and manipulate people’s imaginations and to perpetuate power. And so it was in Mughal times too. Miniature paintings were not created to be framed and hung on walls or to be viewed in galleries, but served most often as supplements to biographies or to eulogise rulers. If the replacement Peacock Throne was an attempt to carry forward the power associated with the original, persistent images of the throne in art attempted to represent grandeur in the face of declining power and control. All elements—from the elevation of the throne towards heaven to the relative position of the various figures in the painting, right down to the decorative patterns—played to the belief that he who ruled from it was supreme, almighty, invincible. Then as now, it would appear that politics moves forward not just through realities, but also through images.

Spanning the ages, from courts and palaces and villages in ancient India, to modern-day boardrooms and living rooms, the evolution and the practice of seating grants fundamental insight into hierarchies determined by gender, class, caste and race, the lives of oppressors and their oppressed, and how the very arrangement of seating helped—and continues to help—accentuate power structures. And it has come to pass that seats themselves have assumed agency, embody sovereignty, and manifest privilege; the politics of posture and position are inherent in communicating an individual’s footing in social hierarchy.

Seats with the same shape and form can be distinguished by material or ornamentation. An ornate seat more lavishly appointed with finer fabric or deeper plush or more intricate carving, is automatically elevated to a higher status than its plainer cousin. A sybaritic seat dressed in velvet and with gold trimmings solicits boldness and reticence, awe and aversion. Chairs at the head of a table—conference or dining—often distinguished simply by armrests or a slightly higher back, confer prominence on the person who assumes it, as does the silk-lined platform upon which the monk sits across from devotees seated on the floor, and the charpai for the head of the village as they address villagers who stand or sit before them. Cultural context and historical influences have had manifest impact on the tradition of seating. The legacy of reverence and distinction afforded to a person sitting cross-legged in padmasana on the floor or on the chair in the middle of the room remains mostly unquestioned.

During the colonial era, chairs were emblematic of authority and privilege—the British believed the chair to be a herald of modernity and culture, civility even—in the face of which traditional Indian postures were scorned as being barbaric and animalistic. Gandhi’s refusal to ascribe to the ideal of elevation as evidence of progress, saw him choosing simply and quietly to sit on the floor. The politics of Gandhi’s seat of choice was deliberate and subversive, calculated not only to make his European visitors physically uncomfortable as they sat in Western clothes on the floor, at the same level as others in the room, but also— one imagines—forcing upon them an uneasy enquiry into inherited notions of Western civility. The baithak, or floor seat, his working space, his low writing table, and especially his switch to traditional attire, were all part of a deliberate image-building exercise. Gandhi’s were carefully considered, politically motivated moves and can be interpreted as metaphors for unity, empowerment, and liberation from colonial subjugation.

No other chair reveals the hierarchies and gendered disparity in practices of comfort in British colonialism as much as the Planter’s Chair. Mid-19th century paintings and advertisements, such as those in the ‘Barrack Furniture and Camp Equipment’ sections in Army and Navy catalogues, suggest that these chairs were initially used in spaces reserved exclusively for men. However, later in the century, they were considered requisite for most colonial homes in India, principally for use on verandahs. Long flat arms, extended by means of a second flat plank that swivelled outward to form a footrest of sorts upon which legs could be raised and spread apart, afforded the user repose and relief from the tropical heat. A Victorian lady could hardly be seen seated in this indecorous manner with its attendant potential for embarrassing indiscretions. Reclining on a Planter’s Chair was therefore mostly the reserve of men: particularly those with privilege, often the head of the house. It was an ideal seat from which to authoritatively pontificate on the topic of the day with those seated close by, on the edges of their upright seats, listening attentively. A reclining seat’s very form suggests a wanton lack of self-restraint; the Planter’s Chair went one further, earning itself the colloquial moniker of the Bombay Fornicator.

POWER TRANSCENDS politics. As Michel Foucault states, it is all pervasive, dispersed and diffused through various mechanisms. It is an everyday, socialised, embodied phenomenon. And, as a consequence, the offer, the refusal, the presence, the absence, the height, the shape, the size, and the detail, of as quotidian an object as a seat can be viewed as an everyday means to situate power. To be afforded or assigned a seat is a display of respect and power, while the absence of a seat implies the denial of authority and privilege. Even in the 21st century across India, when and if given a choice, women are more likely to opt to sit on upright chairs that force a posture. It can be argued that simply standing or sitting on the edge of an upright seat, they can easily spring into attendance. To sink into a plush sofa, to recline on a chaise lounge, to lay on an opium bed, are still deemed privilege even by the most emancipated. To recline is to have earned concession; when no one else present deserves it more, when the important work of the day is done, when no one is watching.

Industrialisation quickly followed Independence in India. The introduction of mass-produced chairs dramatically altered perceptions of the seat. Chairs crafted of cheaper materials granted greater access: the domain of the powerful and privileged was ceded. Designs dictated by models from the West had their drawbacks. Industrial materials were rigid and restrictive; dominant styles imposed straightjacketed postures that hindered movements of the spine. Almost as swiftly as access to the chair was granted, ways were sought to improve, improvise and even escape the restrictions imposed. However, it was only in the late 1980s, that ergonomics as a discipline was introduced at the India Design Centre in the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Bombay, at the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad and the design centres in furniture manufacturing companies such as Godrej. Experts were called upon to proffer advice on how humans should sit and for how long. Designers, in consultation with doctors, modelled chairs that were ergonomically sound, chairs that moved, chairs that forced you to move. Sitting was redefined as an animated, not static activity.

As the masses embraced the privilege of being allowed to sit in and upon chairs, the traditional baithak—a means of meeting and of seating—was less frequented across the country. Has the act of elevation, the assumption of singular seats taken away from the communal meeting where all attendees were at the same level and in similar postures? Are new-age offices with open plans and hot desks inadvertent or deliberate ways of addressing the strictures brought about by the evolution of seating?

If there is one chair that stands out from all others post industrialisation, it is the egalitarian Monobloc Plastic Chair. Found on the street, in waiting rooms, in party halls and in museums, no other seat is as commonplace and ubiquitous. Its nondescript character, its very invisibility, belies its power. Scorned by formally schooled designers for its fickle nature as it adopts motifs, mimics wood or fibre finishes, its role in fulfilling everyday needs cannot be ignored or overstated. Often, a roomful of the Monobloc, neatly lined up in rows are seats for guests at a wedding reception as they wait to meet and wish the newlywed couple who sit upon a kitschy ‘Wedding Throne’. The ‘Throne’—plush and lined with shiny fabric, set against a backdrop of real or fake flowers—grants the couple temporary elevated status of king and queen on their wedding day. It is a prop here, as it is when dignitaries come to visit or when special guests grace occasions, and time on it will be recorded for posterity by means of portraits and photographs. The special seat grants the privilege of darshan, of being seen and accessed, in a manner otherwise only afforded to the venerated.

A chair or a seat does so much more than merely serve the function of seating. It situates power and grants privilege. The seat—through history and across the globe—operates as an instrument of manipulation; to elevate people, to keep others in their place, to grant distinction or deny prerogative. As a means to differentiate; the denial of a chair highlights social exclusion sanctioned in feudal societies, penalisation in prison cells, or deliberate austerity in yoga retreats. In the politics of prominence between men and women, young and old, master and servant, boss and employee, the seat assumes agency. As regulators of posture, chairs define how we sit, and who can sit. The organisation of power and privilege through varied means of governance and social structures employing the seat follow certain common norms in vernacular, colonial and contemporary expressions: elevation, adornment, extravagance are recurrent elements. However, it is the maverick, non-typical seat that we are compelled to appraise more closely; Gandhi’s seat on the floor, the humble Monobloc Chair, and the legendary Peacock Throne. Seats that break through their place in time and space, defy typecasts, and yet command great power, the ones that inspire awe and also discomfort, must be examined for what they tell us about ourselves, our behaviours and our conventions. It is to these that we must look for inspiration, to transcend the typical, and to create new possibilities.

(This is an edited excerpt from Sarita Sundar’s The Frugal to the Ornate: Stories of the Seat in India)