The Rewarding State of Solitude in Pandemic Times

IF SOLITUDE COMES to you uninvited, even two days of it can seem like a hundred years.Or at least that's the conventional wisdom in a world held in thrall to the dogmas of connectivityand interactivity. Even at exhibitions where you might quite justifiably wish to commune quietly with a painting or a sculpture, you're often ambushed by a documentary video telling you all about how the artist went about her business. Or how the restorers saved a legendary canvas from fungus and flaking. And no one—not the airline, not the hotel, not the restaurant, not the bank—lets you go without demanding feedback. How would you rate your interaction with us today, on a scale of 1 to 10? What can we do to improve our service? How likely are you, on a scale of 1 to 10, to recommend us to your friends? We are, literally, never left alone by the vast machine of the world.

But this week, as plazas, piazzas, boulevards, stadia, airports and train stations around the planet have emptied out, we have all been assailed by the question of what to do with ourselves, as we come unplugged from the Matrix. In one way or another, whether we welcome it or are plagued by it, the prospect of solitude has obtruded itself on our consciousness as a species, united in a common predicament by the Covid-19 pandemic, on a scale previously experienced perhaps only during World War II.

Of course, we're all busy keeping in touch with one another and immersing ourselves in Netflix, Amazon Prime and the varied delights of social media. The airlines, hotels, restaurants and banks are still sending us lengthy messages, regretting the pandemic and assuring us of their attention at all times. But we are physically grounded, locked down, parked at home, under house arrest. To those of us who work from home and enjoy the comfort of the arrangement anyway, this poses no immediate challenge other than the curtailment of walks and other intermittent outings. To those programmed to seek the great outdoors, to be constantly up and about, to meet and be convivial, this is a judicial sentence.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

I do not exaggerate when I say that the pandemic has withdrawn from us a fundamental feature of our modernity: the liberty to sink our identity voluntarily in the larger collective and to retrieve it at will. Annotating Edgar Allan Poe's short story 'The Man of the Crowd' in his memorable essay, 'The Painter of Modern Life' (1863), the poet and critic Charles Baudelaire celebrated the quintessential modern, metropolitan personality: 'The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world… the lover of universal life enters into the crowd as though it were an immense reservoir of electrical energy. Or we might liken him to a mirror as vast as the crowd itself; or to a kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness, responding to each one of its movements and reproducing the multiplicity of life and the flickering grace of all the elements of life. He is an 'I' with an insatiable appetite for the 'non-I', at every instant rendering and explaining it in pictures more living than life itself, which is always unstable and fugitive.' What happens to this endlessly experimental, cosmopolitan subject, voraciously approaching the unpredictable banquet of metropolitan life, when the crowd is ordered indoors, the arcades are filled with vacancy and the city, switched off, falls silent?

By a cruel irony, Covid-19 attacks the most human of human instincts: the need to come together, to speak, gossip, celebrate, pray, grieve or feast together.The news from Italy is particularly heartbreaking. The strength of Italian society—manifested in its lively family gatherings, the warm affection robustly displayed, the bonds that connect old and young across generations—has become its weakness in this crisis. Here we are, all isolated from one another, like monks in our cells, divided by an invisible yet highly effective enemy.

OUR PRESENT STATE of self-siege would be a good time to think about the varieties of solitary experience, to adopt a William Jamesian turn of phrase. And we might draw on more than the title of his 1902 classic, The Varieties of Religious Experience. Discussing mysticism as an altered state of consciousness, transformed and transformative, James argues that mystical experiences carry authority and visceral significance only for the individuals who go through them. They cannot carry the same ring of conviction for those who have only heard or read of them second-hand. Despite this fundamental incommunicability and lack of scientifically provable repeatability, mystical experiences can make a claim to their own authenticity, parallel to that of rationality. In the same way, I would suggest, the uses of solitude cannot easily be communicated or demonstrated. They must be undertaken in the spirit of an empirical enquiry. As the ancient alchemists knew, as did Tagore, Ananda Coomaraswamy, J Krishnamurti and Mahatma Gandhi, the only possible laboratory for such an enquiry is the bodied, individual self.

A major reason for our discomfort with the experience of solitude lies in our social conditioning, which conflates solitude with loneliness, isolation, friendlessness. To be with others—to be recognised, accepted and included by others—is to achieve social validation. To be left out is to be without social validation, to be an illegal immigrant in the community. Worse, we've been trained to see solitude as a penal condition, a punitive imposition. We design solitudes that emphasise, by brutal contrast, the vital importance of sociality. As children, some of us may well have been ordered to stand in a corner or been locked in a room, perhaps a dark room. Solitary imprisonment is intended to remove people from the company of their peers, to stigmatise them as a burden on or a hazard to others, to twist their individuality from an enabling position of confidence into a condition of self-imperilment. The isolation ward is where individuals, exiled from the plural of social being and marooned in their singularity, are quarantined so that they may not infect others. Despite medical explanations, the blow cannot be softened. They're left with a soul-depleting sense of guilt and humiliation for company.

Social and political tyrannies design the worst solitudes. Consider the dread words: 'solitary confinement'. During the early phase of his incarceration in Reading Gaol, Oscar Wilde was forbidden access to books and writing materials. A rule forbidding prisoners from speaking to one another was strictly enforced. This spelt death to a poet and playwright, especially one such as Wilde, whose art was based on the interplay of call and response, provocation and repartee. Writing in desperation to the home secretary, asking for these restrictions to be lifted, Wilde wrote: 'Horrible as all the physical privations of modern prison life are, they are as nothing compared to the entire privation of literature to one to whom Literature was once the first thing of life, the mode by which perfection could be realised, by which, and by which alone, the intellect could feel itself alive.' True, sterner souls have withstood far worse periods of imprisonment, but Wilde's cry for help reminds us that, however idiosyncratic a writer might be, language is first and foremost a social medium, a medium intended to bridge minds and worlds. As Wittgenstein observed, there can be no such thing as a private language, in the sense of a language that makes sense only to one person and is unlearnable and untranslatable by anyone else.

States of lockdown can produce, also, forms of solitude that are traps. Forced seclusion, without access to medication and therapy, can be lethal to individuals wrestling with mental health issues or behavioural syndromes. Already at risk, such individuals are placed—as we have seen in the long-running and inhuman lockdown in Kashmir—in situations of extreme vulnerability. They embody, in ways unimaginable to those who do not share their condition, the horror that many of us are beginning to confront in a gradual manner: the way in which a lockdown can alienate us from others, and from ourselves. In the war with the pandemic, the enemy is invisible, is everywhere, could be anyone and could even be the person standing in front of you in the mirror.

For two years, two months and two days in the late 1840s, the philosopher Henry David Thoreau retreated to a 'tightly shingled and plastered' cabin on Walden Pond, set in a wooded area near Concord, Massachusetts in the US, that belonged to his friend, the writer and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson. Walden Pond was not far from urban habitation. Thoreau's mother kept him supplied with food, the Emersons were close at hand and other friends dropped by from time to time. This was no trek into an uncharted wilderness, no demon-haunted struggle to survive against all odds. Nor was that Thoreau's ambition. What he intended was an experiment in living close to the land, at the least possible cost to the ecology, balancing the need to delve deep into the self with the need to evolve warm relations of mutuality with friends and neighbours. Walden; or, Life in the Woods, published in 1854, was an account of this experiment. Part memoir, part meditation, it records how he spent hours in quiet contemplation yet also welcomed more visitors than he had done as a townsman. He grew keenly attentive to animal and plant life, to nature's rhythms and cycles. Walden is an account of the gifts of this calibrated solitude: lucid and realistic self-awareness, the adoption of a measured economy in all things, a diminution of the demands to be made on the planet. Above all, a life led consciously, not sleepwalked through. Towards the end of Walden, Thoreau remarks, 'Only that day dawns to which we are awake.'

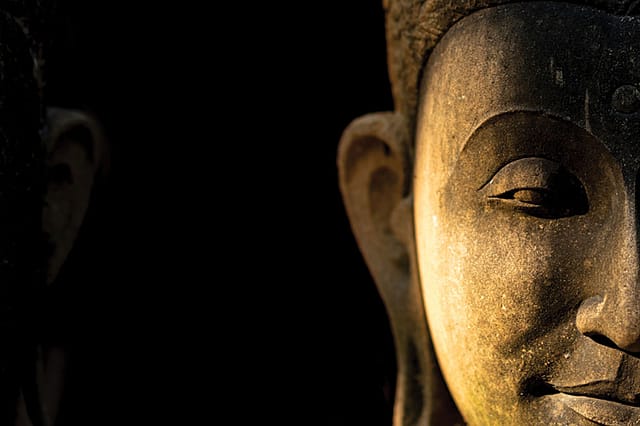

Traditionally, the achievement of such a constant, centred, stereoscopic awareness has been—along with tranquility—one of the aims of monastic or meditative seclusion. In the contemplative life as it has historically unfolded, let us say, at Sri Ramana's ashram, the Greek Orthodox monastery of Mount Athos or a Buddhist vipassana centre, the practice of mindfulness coupled with a voluntary spell of silence can bring about—unlike for Wilde in his first years at Reading Gaol—a regeneration of speech. A true solitude allows us to renew the resources of the self. It may well offer us visions and revelations. Less dramatically, yet no less efficaciously, it can quieten what practitioners of meditation call our 'monkey mind', so that we may reflect on recurrent patterns in our lives and discover possibilities of liberating ourselves from habit,seeding a harvest of creative self-disruption. Instead of a validation granted by others, solitude gives us the space and time to achieve autonomy. To revive the terminology first presented by David Riesman, Nathan Glazer and Reuel Denney in their now-forgotten classic of sociological analysis, The Lonely Crowd (1950), solitude can lead us from being 'outer-directed' to being 'inner-directed'.

IN A THOREAUVIAN spirit, the beat poet Gary Snyder spent two summers working as a lookout or firespotter with the US Forest Service in Washington state. In 1952, at age 22, he served at the 8,132-ft-high Crater Mountain and, the following year, at the 6,112-ft-high Sourdough Mountain nature reserve. Snyder's experience of these two seasons spent in solitude in a high watchtower set him on a lifelong journey of meditation and ecologically sensitive practice. He turned, soon enough, to Zen Buddhism as a key source of inspiration. In 'Mid-August at Sourdough Mountain Lookout', which I quote here in its entirety, Snyder conveys something of the incommunicable expansion of consciousness that he had experienced:

Down valley a smoke haze

Three days heat, after five days rain

Pitch glows on the fir-cones

Across rocks and meadows

Swarms of new flies.

I cannot remember things I once read

A few friends, but they are in cities.

Drinking cold snow-water from a tin cup

Looking down for miles

Through high still air.

If we seek solitude out and make it our own, it can reward us with the repose to imagine into being a new, more productive and equitable relationship with ourselves, others, and the world.