The Renaissance Physicist

IN THE DECISIVE years after India gained independence, Homi J Bhabha argued persuasively for a stand-alone organisation, reporting directly to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, to oversee the development of atomic energy. In a note to Nehru on April 26, 1948, Bhabha stressed the need for India’s atomic programme to be conducted in absolute secrecy and to be directly answerable to the Prime Minister. His access to Nehru no doubt helped him have his way, though Nehru did not require much convincing about setting up an Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) on a footing completely different from any other wing of the government.

Was Bhabha motivated, at least to some extent, by a desire to set up his own fiefdom? The criticism from another eminent scientist Meghnad Saha might suggest so. Saha opposed every aspect of Bhabha’s plans, saying the AEC could not precede measures to encourage industrial growth and availability of trained nuclear physicists. Saha, who became an independent MP from Calcutta in 1952 with the help of Left parties, often attacked India’s nuclear policy in Parliament. Sadly for Saha, who had risen from humble roots, not only lost to his more privileged rival, the passage of time has only proved Bhabha right. It is no coincidence that since Nehru, the department of atomic energy has been under the prime minister.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

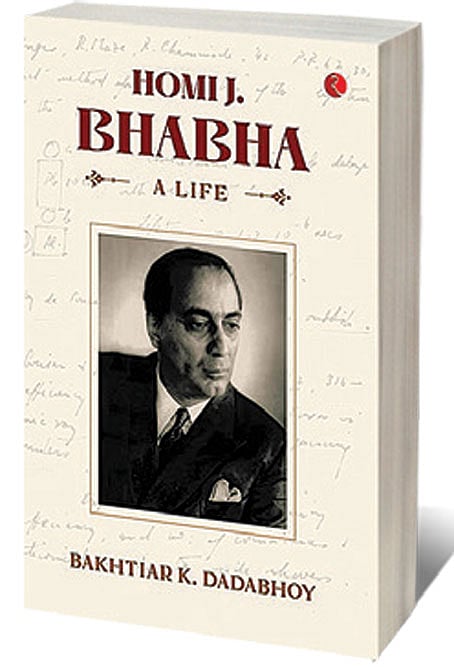

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

The details of the fascinating journey of India’s nuclear programme are set out with care and precision in Homi J Bhabha: A Life by Bakhtiar K Dadabhoy, who has previously written on other renowned Parsi figures like JRD Tata and Zubin Mehta and also on Parsi communities in India. Currently an additional member of the Railway Board, Dadabhoy was a keen debater at school and showed early promise as a diligent scholar. His homage to Bhabha, which does not skip the warts, can be dense and tests the reader but rewards endurance. Its initial chapters tell the story of Indian science through towering personalities such as CV Raman, Jagadish Chandra Bose, Asutosh Mookerjee and later S Chandrasekhar and Saha. The introduction of Bhabha, replete with personality clashes, is a much-needed 360-degree appreciation of the great physicist and father of India’s nuclear programme.

Dadabhoy’s early chapters and the final ones dealing with Bhabha taking charge of the AEC, are the best parts though the book also deals with the physicist’s personal relations and artistic talents. While no doubt of interest, the nitty-gritty can get a bit burdensome. But the book comes into its own as it reveals the early challenges to India’s atomic ambitions that serve to underline how vital the autonomy and resources, not to mention the talented and dedicated work force, were to developing India’s ability to deal with hostile, nuclear armed neighbours. In doing so, it also reveals missed opportunities that might have helped India to prepare for—even deter—the Chinese aggression in 1962. The story is worth retelling.

Briefed by US intelligence that China might be able to conduct a nuclear test by 1963 (it happened in 1964) President John F Kennedy offered to help India carry out a test of its own. While no doubt keen to counter China, Kennedy noted that a Chinese test poses a “political and military threat to India’s security.” Nehru shared the letter with diplomat G Parthasarathy who discussed it with Bhabha and intelligence bureau chief BN Mullick—both said the offer should be accepted. Parthasarathy told Nehru to do the opposite. He was possibly aware that Nehru was heavily invested in the non-aligned movement and accepting US help would hurt his effort to emerge as an advocate of global disarmament. Had Nehru accepted the offer, it might have made China think twice and deterred Pakistan’s adventurism in 1965.

Yet, Nehru did understand that peaceful nuclear energy and security are twinned. To India’s good fortune, Bhabha’s legacy has proved enduring and made India’s nuclear programme self-reliant.