The Progressive in Paris

IT WAS AN uninterrupted journey by sea, broken by the lapping waters, which was taken by SH Raza in September 1950 and which finally brought him to Marseilles. He was accompanied by Akbar Padamsee who had also decided to live and work in Paris for a while. Raza recalled, ‘When the ship left, I looked at the shores of Bombay with tremendous emotion in my heart. Slowly, the country receded and the boat took us over into the space of the ocean.’

Padamsee vividly remembers the journey which he undertook after speaking to Raza, ‘No. I didn’t know anybody and I was in the School of Art, so there was no one—I was 18. Raza was six years older than me.’ He mentioned, ‘We went by the same boat—SS Stetenham —an English boat. It was a wonderful trip with him. You know I was reading a lot of books and Raza didn’t know English. His English was poor or nil. And he was trying to study. So the books I read, I talked to him about them. He said, ‘Wonderful, when did you read them?’ I said, my brother Nuruddin has a big library.’ According to Akbar he also learnt how to knot a tie on the ship and would practise it for hours.

They reached Marseille eleven days later on October 2nd where a representative of the French Government met them and they were put up in a hotel. The next day they travelled by train to Paris and were received at Gare de Lyon by Ram Kumar at 8 am. A room had been fixed for Raza at Rue Delambre at Montparnasse where all the important painters, French and otherwise, lived and worked. Raza did not take long to freshen up and rush out to look at the city he had dreamt about for so long. ‘It was an extraordinary experience. I loved these boulevards and buildings and the look of the cafes and houses. I discovered at the crossroad of Boulevard Montparnasse and Raspail an enormous statue of the writer Balzac by the sculptor Rodin…Now, here was a great sculptor portraying a great writer. The city honouring these two artists was fantastic and the solidity and sculpturesque quality of the statue right in a public place was a revelation to me.’

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

On seeing a poster announcing an exhibition of Matisse at Maison de la Pensee Francaise, Akbar and Raza went to see it and this was the very first show that he saw in Paris. ‘It was extraordinary in the sense that it worked with two dimensions, nearer to the Indian concepts in which we were getting involved and interested. It was not the realism of the post-Renaissance period. It was solidly constructed, where colour prevailed…Around us there were beautiful men and women, well dressed. Musical concerts being announced, other art events. There was a poster which said in French, ‘Life begins tomorrow.’ I said, ‘No, Life begins today.’

Although Raza’s dream had come true and he was at last in Paris, the city after the war was a distilled place. It had been the metropolis of the 20th century where artists, writers and thinkers had congregated to realise their art and to lay the paradigms for modernity. As Gertrude Stein writes, ‘The reason why all of us naturally began to live in France is because France has scientific methods, machines and electricity, but does not really believe that these things have anything to do with the real business of living. ... And so in the beginning of the twentieth century when a new way had to be found naturally they needed France… But really what they do is to respect art and letters, if you are a writer you have privileges, if you are a painter you have privileges and it is pleasant having those privileges. … well that too is intelligent on the part of France and unsentimental, because after all the way everything is remembered is by the writers and painters of the period, nobody really lives who has not been well written about and in realising that the French show their usual sense of reality… .’

Despite the effervescence, the Paris that Raza saw had changed from the early part of the century, and suffered from a sense of exhaustion. The haunts of the artists and writers, like Café de Flore, wore a deserted look and the masters were present by their absence. The Ecole de Paris had run its course, leaving behind the last remnants of abstract art with painters like Pierre Soulage, Nicolas de Stael and Serge Poliakoff. The scene had shifted to New York even as Paris harboured a melancholy nostalgia for the masters of modern art. When one of the last of them Nicolas de Stael, at the age of forty-one committed suicide on March 16, 1955 by leaping from his eleventh storey studio terrace in Antibes, Paris mourned.

YET RAZA WAS fortunate to have his colleagues in Paris. Ram Kumar recalls, ‘When Raza first arrived in Paris in 1950, I was there at the station to welcome him. I still remember how, even as he alighted from the train, he was infused with enthusiasm for Paris, and how within minutes he was talking about the Louvre and Picasso. I attempted to introduce him to other dimensions of the city—the place, the people, the weather, the life—but he was lost in other dreams. He was already planning his schedule of study, when he would work and when he would visit other exhibitions and museums in the city. He valued time immensely and wanted to use it for work and work alone. He felt he might never get such a chance again, and wanted to experience this once in a lifetime opportunity to its fullest—little did he know at that time that he would be spending his life there.’

The artist was to visit the museums in a systematic manner to look at the original works which he had wanted to, for so long. He could hardly wait to go to Jeu de Paume the next day where he stood transfixed before a portrait of Vincent Van Gogh and tears came to his eyes. Next to this was a highly orchestrated works of Cezanne and he studied these with great interest for they consisted of great depth and complexity. He also found Gaugin extraordinary and closer to the oriental aesthetics he was familiar with.

Raza was to join the Alliance Francaise to improve his French. Soon after he was to get admission to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and was allotted to the Atelier of Heuze, a fairly well-known portrait painter. In the course of time he got to know Edmond Heuzé who said to him, ‘Look, Raza, ultimately you have nothing to learn at this school. Of course, you can practise, which is good. Art expression is practical work: paint and study. I would give you every possible instruction ideas that you would like to know. Ask me questions, but work. At home you are already a mature painter. You come from a great civilisation and culture. I will give you all the papers that would be necessary but come and see me once a week at least.’

Raza found that he was right and that the training did not happen in the school where the students were rather immature but for three or four friends who had talent. But amongst the students was a young girl who was not just very pretty but very talented and Raza became very friendly with her. This was Janine Mongillat.

In these early years, life was very busy for Raza. As he wrote to Mr. Journot, his friend and the French Councillor in Bombay some years later, ‘Please forgive me for the delay in writing to you. Often and again I thought of doing so informing you about me and my work, my happiness and my problem…. My first attempt was to acquaint myself with the art treasures of Paris and to have a general knowledge of the history of Art in Europe—both ancient and modern….My approach has been, of course like that of a student of ‘aesthetics’ rather than that of an archaeologist or a historian. The Ecole des Beaux-Arts opened in the middle of October and I joined it as ‘Etudiant Libre’ (that so because I am over-age). I have taken the painting course of the morning and the drawing classes in the evening. As I told you in Bombay, I wanted to do a lot of drawing and painting from life and I am as convinced now as before of the importance of drawing as the fundamental basis of a good painting. I have of course, the afternoons and holidays for my experimental work and for studies in museums and libraries.’

Raza was working harder than ever and seemed barely to have any time on his hands. He was driven because it was a make-or-break situation. But there was a sea change in his work as well. He mentions to his younger brother Mohsin who had asked for financial help, ‘It’s not asking too much from a brother (who himself feels morally bound to help you) for assistance. I even like the confident tone of your letter. But dear one, do you know that this one is not the healthy young man of 1940s, proud and confident who could work 16 hours a day and whose work brought back money surer than the surest trade? All has changed with me now. I have undergone a period of study and evolution for which I had to pay with my blood and the realisation has cost me my life. This is no mystic statement—actually I refer to the skeleton I am reduced to now—my physical being which cannot now stand four hours work—my frail hands which at the age of 30 tremble constantly. Nor do I wish that the above statement should give impression of complaint. I am, on the contrary, happy indeed to have lived and lived fully and my way, according to my own values and to have worked for the sheer joy of working…Now some facts about my life. My work has completely changed. The pictorial conception I am developing is totally different—which I will not deal with, since it will take me pages to explain. I will only show one difference which is very significant and which at the moment concerns us. This is that I need now at least four to six weeks for a painting—if I work regularly—whereas in Bombay I used to leave home with six papers tucked under my arms—and by the evening I will come back with at least four paintings—sometimes all the papers were covered. Now this one painting for which I give more than a month [of] hard work is sold for about 300 rupees—which is hardly sufficient for a month’s expenses for one person in Paris. The only fortunate thing is I sell almost everything I do and so far I haven’t starved.’

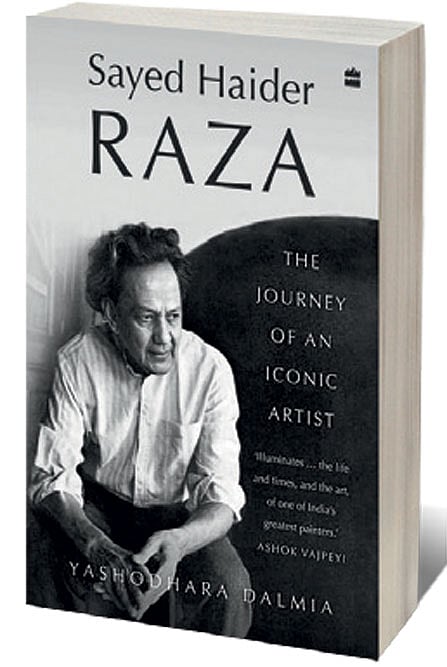

(This is an edited excerpt from Sayed Haider Raza: The Journey of an Iconic Artist by Yashodhara Dalmia | HarperCollins | 264 pages | Rs 899)