The Missing Frame

The life of Minnette de Silva is apt for excavation. The groundbreaking contributions of Sri Lanka’s first woman architect towards modernist urban aesthetics in a newly independent Sri Lanka that was configuring its identity and recalibrating its precarious ethnic balance are often overlooked. De Silva is a historical figure worthy of mythologising. She belonged to a patrician political family—they hosted everyone from the likes of Nehru to Gandhi—yet died penniless. Choosing to never marry through her life, she had romantic trysts with Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, the celebrated Swiss-French architect better known as Le Corbusier, and David Lean, the Oscar-winning director of Lawrence of Arabia. She was a trailblazer, taking after her suffragette mother in fearlessly occupying the public realm.

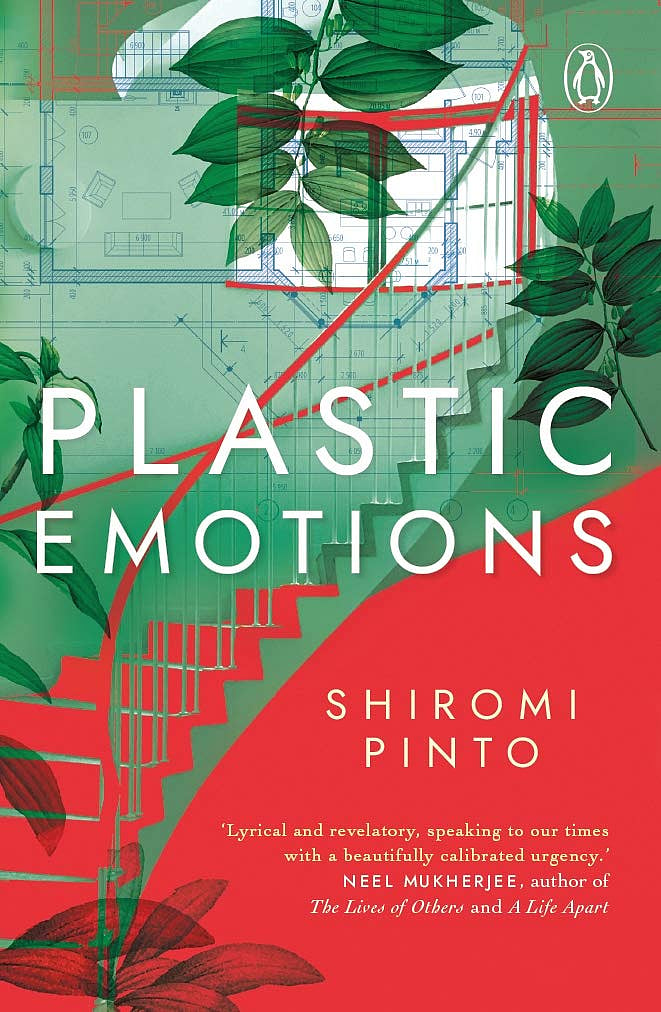

Plastic Emotions, Shiromi Pinto’s second novel is a fictionalised account of de Silva’s life between 1949 and 1965 pouring novelistic concoctions into its historical foundation. The book begins with a series of lovelorn letters sent by de Silva to Le Corbusier. She’s in the process of moving back from London to erstwhile Ceylon on the insistence of her father. Their messages to each other are as full of yearning as can be expected on a sedate BBC drama. He refers to her as his oiseau (bird) and she refers to him as Corbu. ‘Each step takes me back to Bridgwater, back to that moth’s wing of a moment that swept fortune into my hungry mouth,’ she writes. The novel mercifully moves away (at least partially) from this stilted epistolary framework and flips back and forth between Le Corbusier, as he embarks on his biggest challenge, designing the city of Chandigarh, and de Silva, as she attempts to make a name for herself in Ceylon. Meanwhile their correspondence with each other continues.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Reassembling de Silva’s life without losing the verve that powered her work is a mighty task. Unfortunately, Plastic Emotions is malformed, like that infamous botched fresco of Christ in Spain. The novel is strongest when we are privy to de Silva’s ingenuity particularly her synthesis of Western and Eastern styles in her architectural practice. ‘…the Ariyapala Lodge is more than a house; it is the culmination of an architectural tradition that goes right back to Anuradhapura itself.’ Pinto also has a poetic ear for sentence construction. ‘It is that night that I inscribe your name in my diary three times, as if forging your signature in that intimate space will bring you closer to me. It is an incantation—a mantram—the repetition of which should draw you into my orbit, or me into yours.’ Yet, do these occasional coruscating building blocks serve any purpose in a crumbling edifice?

Pinto makes the imposing Le Corbusier an equal part of the narrative and as a result de Silva recedes into the background of her own story. Pinto no doubt nobly attempted to reframe the power balance between this young, brilliant Sri Lankan woman and the much older, pre-eminent figure into one of equals. Le Corbusier wasn’t just a generous mentor to de Silva, he was equally inspired by her vitality and brilliance, Pinto seems to signpost. Yet by relegating the novel’s proceedings to the 16 years in which de Silva and Le Corbusier exchanged letters, Pinto keeps de Silva at an arm’s length from us. We understand little of her outside the performative mode of her words. Who was the de Silva who finally decided to turn her back on Sri Lanka in her later years, or the de Silva who made a life in Bombay before she moved to London in her twenties?

While it’s Pinto’s prerogative as a novelist to take liberties with de Silva’s story, some of her choices for fictionalisation seem gratuitous. The characters who exist outside de Silva’s orbit, are one-dimensional, poorly integrated placeholders for political commentary. De Silva’s own family is flattened too. Her sister, Anil ‘Marcia’ de Silva, who was a journalist, communist, and pioneer herself, is more domesticated on page than she was in real life, saddled with a loving husband and child. Agnes, her mother, one of the prominent female faces in the Sri Lankan independence movement and voting rights for women is largely depicted withering away due to cancer. Her brother Frederick has been excised from the story. How can the novel attempt to understand Minnette de Silva, if it rearranges the pivotal figures in her life?

Much like the substance it refers to in its title, Plastic Emotions leaves readers cold.