The Man Who Did Not Bend

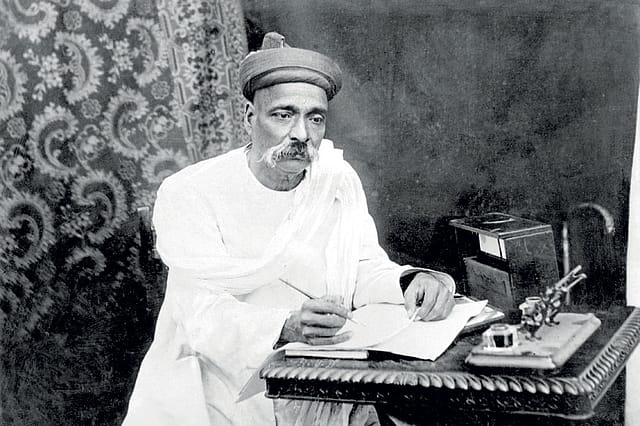

BAL GANGADHAR TILAK (1856-1920) is perhaps most famous for thundering, “Swaraj is my birth right, and I shall have it,” in defiance of the British Raj. In fact, were I to resurrect my school textbooks, this remark would appear as their main highlight on Tilak. The other popular detail concerning him is that he was the leader of the “Extremist” wing of the Indian National Congress. Simply put, until he came along, the nationalist movement was moderate, committed to non-provocative means, and, therefore, limited in potential and its impact. Tilak, however, urged “militancy, not mendicancy,” a call that made him enemies within the party, eventually even splitting the Congress during its 1907 session. It was not a pretty turn: Tilak was barred from speaking, and our esteemed freedom fighters flung chairs and shoes at one another.

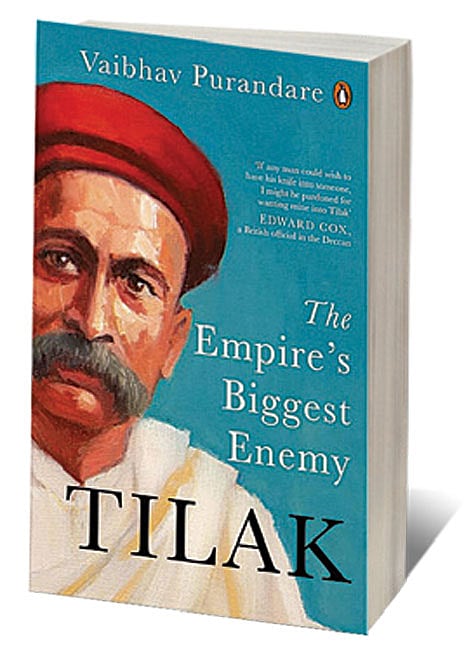

But politics is often a rough affair, and we see a good deal of this in Tilak’s latest biography. Vaibhav Purandare’s Tilak: The Empire’s Biggest Enemy is a well-written, enjoyable new English account of the lokamanya and his eventful life. There are not many books on the man today, even though, as Purandare observes, he laid the foundation on which leaders like Mahatma Gandhi would build India’s greatest mass movement. The last notable biography was Dhananjay Keer’s 1959 volume, followed by some scattered studies, as by Richard I Cashman. At present, Prashant Kidambi is reported to be working on a biography as well. Either way, Purandare’s neat volume will serve well in introducing a new generation of readers to this “Father of Indian Unrest”— as a white critic branded the Maharashtrian nationalist.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The book stands on the shoulders of established scholarly works and biographies—in English and Marathi both—with the addition of newspaper sources and material from Tilak’s collected writings. Its structure is, like good old-fashioned biographies, chronological, and we see Tilak’s transformation from a Pune-based professor of maths and law into a nationalist journalist and a mass leader by the turn of the 20th century. There are areas where I felt Purandare offers too much detail—for instance, the internal politics of the Deccan Education Society, of which Tilak was a founder. But perhaps this is essential to making sense of the man’s character and style. In fact, given that we have few windows into Tilak’s interior life, it is through these petty conflicts that we form a sense of his core personality; of the person before he became an icon.

Purandare is an admiring biographer. But he is, for most part, also cautious. He does not, for example, hesitate to point out the undignified newspaper feud Tilak engaged in with his friend-turned-foe, Gopal Ganesh Agarkar. On questions of social reform and women’s rights, he adds how Tilak aired “retrograde” views. So too, Purandare confirms that while the lokamanya’s transformation of Ganapati worship into a public festival was intended to galvanise people and release politics from rarefied spaces into the streets, it was also rooted in a desire to flex Hindu unity and communal muscle. Romantic accounts that cast Tilak as the mastermind behind the Chapekar Brothers’ assassination of British officials are also challenged; Purandare concludes that Tilak had only the vaguest, most peripheral links to the event.

That said, there are some awkward assertions in the book. For instance, when Tilak contested against GK Gokhale for a legislative council seat, the latter requested the Times of India to stop attacking the lokamanya. Gokhale’s concern was that this could backfire and end up building sympathy for Tilak, scuttling his own chances. It is a relatively minor incident, but Purandare exaggerates it as “an act of collaboration with the colonial system of oppression.” The remark stands out, because, where for the most part Purandare is measured in his tone, here he is unfair to Gokhale. The moderates were not sell-outs; indeed, if Gandhi built on Tilak’s work, Tilak himself was a phenomenon that could not have emerged without moderate nationalism first preparing the stage.

Similarly, Tilak’s criticism of Pandita Ramabai drew my attention. Ramabai had converted to Christianity and was accused—perhaps with reason— of encouraging girls in the home she ran to also jettison Hinduism. Tilak, in one of his editorial volleys, suggested the lady should no longer style herself “Pandita” but “Reveranda”. Purandare presents the term as a Marathi rendering of “reverend”, spelling it “reverenda”. Scholars like Meera Kosambi, however, have read it as “reveranda”, with Tilak evidently punning on “randa”, or whore.

Whether he meant it that way or not is debatable, but a glance at the Marathi original does suggest that the term features an “a”, not “e”. It is a small detail, but offers an insight into the unbecoming tone our public hero was capable of taking when aggravated.

Indeed, his tongue and pen cost Tilak many friends. As he admitted, “The chief fault…in me is my manner of expressing myself in strong and cutting language…I often fall into the error of giving sharp and stinging replies.” Equally, however, Tilak’s masterful deployment of sarcasm was integral to the success of his Marathi journalism. Indeed, it was this that would in the late 1890s and again a decade later invite trouble, when the Raj accused him of sedition and jailed him. Purandare does not venture into it, but there is evidence that the lokamanya’s supporters also weaponised crude language. The songs sung at the Ganapati and Shivaji festivals, for example, not only attacked Muslims but also Tilak’s political opponents. Gokhale, thus, was lampooned as a “eunuch” and “dirt of the gutter”.

As a chronicler, Purandare is effective in reconstructing Tilak’s life. Certain episodes the book spotlights are fascinating: I did not know about the lokamanya’s purported role in a years-long revolutionary scheme to produce weapons in Nepal, for instance. But sometimes the emphasis on sequential narration eclipses the need to pose some of the bigger questions. To illustrate, Tilak was a radical in politics but a gradualist on social reform. The moderates he criticised flipped this: they were radical with social issues, gradualists in politics. Through the book we catch glimpses of the resultant tension, but I would have liked a more sustained exploration. Much of Tilak’s critique of the moderates could, in fact, be held up against him on social questions—what do we make of this?

So also, Tilak’s usage of the term “Hindutva” is noted in passing. This could have been a useful juncture to explore the idea of Tilak as a Hindu nationalist before Hindutva (as articulated by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar) made its appearance. And to ask if and how this Hindu nationalism waxed or waned as Tilak graduated from provincial celebrity to pan-Indian fame. That is, in a quest to record all the milestones of the lokamanya’s life, Purandare misses some analytical possibilities. Tilak’s discomfort with—and sometimes crude attacks on—leaders of the non-Brahmin movement is also a fascinating subject but receives short shrift in the book. I was also surprised not to find an epilogue. While the Introduction offers an overview of Tilak’s historical importance, I would have liked to read Purandare’s take on why the lokamanya matters today.

But I suspect I am fussing too much. Purandare sets out to tell Tilak’s life story, and this he delivers well. I hope young readers especially pick up the book, not merely to learn about a remarkable historical figure, but also a man who, at great cost, refused to bend, and had the courage of his convictions. Even if sometimes—on caste, religion, and women—his ideas placed him on the wrong side of history. But then again, no human being is perfect, and the lokamanya too was ultimately human. Purandare acknowledges this—and I suspect Tilak too would have accepted the charge quite readily.