The Magic of Mermaids

IT IS NOT often that we open a graphic novel about mermaids and witness stunning lyricism leaping off its pages.

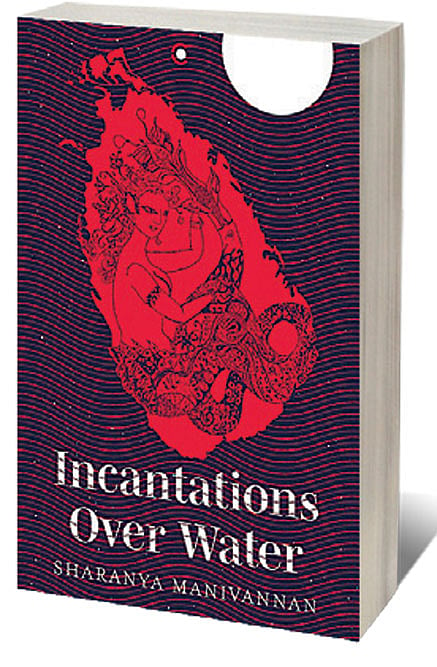

Sharanya Manivannan’s gorgeously illustrated, evocative novel Incantations over Water weaves a tapestry of lore, mythology, magic, and history featuring mermaids, those fantastical sea-based creatures we tend to assume sprang from European imagination alone. Except that in Manivannan’s rendition, they seem less fantastical, more victims of anthropocentricism taken to an extreme, and existent across mythologies. As Ila, our protagonist and storyteller, berates us, “You, humans, you like the stories in which one of you meets one of us. This is why you don’t really know the stories of us.”

Ila is a mermaid residing in the Kallady lagoon in Mattakalappu (or Batticaloa), Sri Lanka, who lures the reader with tales about merfolk and the history of her home. In interviews, Manivannan talks about how when she visited Mattakalappu, her ancestral home, she noticed mermaids appearing everywhere but in folklore. Elsewhere, Manivannan writes, “the meen magal [mermaid] was just there, in symbols and songs”; just not in narratives.

Acknowledging this “folkloric void”, Manivannan works by pulling out story threads from the world’s tapestry of mermaid lore. While telling us about herself, Ila borrows stories—seeking them “like the moon seeks itself in still water”—from Southeast Asia to South America, trying “to find myself in them”.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The sea appears as a character in the novel, almost a living being with a force of its own, opening its “maw” and swallowing all that is near it on land. Its depths filled with a wondrous universe brimming with life, the sea is also half home to Ila, whose other home is Batticaloa and the connection she feels to it after having witnessed so much history and loss on its land. Even as Manivannan has Ila narrate her story through all the lacunae, she uses these fantastical elements to talk about grief, loss, and trauma that Sri Lanka itself has undergone in the course of its history of colonialism, Civil War, and the tsunami. For the larger part of the novel, Ila tells us about herself (through the stories of other mermaids like her) and her land. But it is only towards the end that we get a glimpse of her own longing and yearning to be seen, to be heard, to not be alone. To be heard is to have one’s existence acknowledged. When Ila asks to be heard, she is essentially asking to be realised, storied, contextualised.

In many instances, Manivannan depicts the sea and the night sky as reflections of each other. Ila calls a boatman “another beautiful bearer of light”; the boat has an “asterism” within it; corals “orbed” around Ila’s wrists. Deep indigo has been used as the major colour palette, on which drawings are then depicted in white alongside contrasts of vivid colours, mostly reds and yellows. The overall effect is that of being enticed into a magical world of deep waters under a mystical night sky.

The language is beautiful and suffused with imagery. A diver “rides up through the water like a sun-seeking thing”. Ila implies stories about “the power-hungry and the poetry-impelled” projecting their desire for glory onto other places. A wrecked and lost ship takes on “transformed sentience” in the form of lush reefs.

Sometimes though, Manivannan can be a tad bit too generous in her use of nautical words. It would also help tremendously if there was an appendix giving context to the many mermaid folklore mentioned in the novel. Having to look them up online steals from the experience, and breaks the narrative flow for the reader.

Split into 12 chapters, Incantations over Water is an exploration about memory, home, loss, and the power of narratives. Densely researched and ecofeminist in its approach, the novel is an enthralling poetic and visual feat.