The Last Action Heroes

When I heard an American had written a book about the 'funky' Hindi cinema of the 70s, my first reaction was a proprietary sense of unease. Something like the emotion that (I am told) my Bengali friends experience when I, a mere north Indian, have the temerity to discuss Satyajit Ray's or Ritwik Ghatak's cinema even though some of the cultural and lingual nuances are beyond my grasp (and the DVD subtitling is often terrible anyway).

Which is to say that even before opening Todd Stadtman's Funky Bollywood: The Wild World of 1970s Indian Action Cinema, I was readying to roll my eyes at a bit of analysis that 'didn't get it', condescension directed towards movies I thought highly of—or, just as bad, an undiscerning celebration of mediocrity just because of its perceived kitsch value. If these movies have to be celebrated or trashed, it's people like me who should do it, I muttered to myself —not someone who didn't grow up with them and has never even lived in India. I pictured Stadtman as Bob Christo in the climactic fight scene of Disco Dancer, and myself as Mithun laying a bit of the old dhishoom-dhishoom on this firangi noggin while Helen, escorted by dancers in black-face, cavorted about us in a peacock-feather outfit, and we all dodged around a pool containing smoky pink acid and plastic sharks.

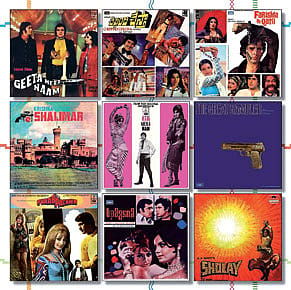

However, this defensive nervousness about the book soon faded. It's true that Stadtman was drawn to 70s Hindi cinema by its colourful over-the-topness, and that his publishers have had much fun with glitzy photos and trivia boxes (for example, the sequence of images showing a mini-skirted Jeetendra transforming into a snake in Nagin, while Sunil Dutt stands by stoically with rifle in hand), but this is not in essence a frivolous book hurriedly thrown together to capitalise on a market for corn and cheese. Stadtman has put thought into it. He writes with affection, and with the ambivalence that often makes this sort of writing so compelling—where one gets the sense that the author is struggling with his own responses to a film. Fans of pop culture that tends to get labelled as 'trash' (or 'great trash', to use Pauline Kael's simplistic formulation for movies she enjoyed immensely but couldn't think of as having artistic merit) will know the feeling.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

Non-Indian fans of Bollywood—such as the bloggers Greta Kaemmer, Beth Watkins, Mike Enright and Carla Miriam Levy—all have their own stories about how they became interested in Indian cinema. In his introduction Stadtman explains that as a longtime fan of cult movies, he came to 70s Bollywood after having been through Mexican lucha libre filmography as well as Turkish superhero mash-ups: he was seeking 'speed, violence and garish style […] but cloaked in a cultural context that makes it all seem somehow fresh and new again'. Given this brief, and the glut of eye-popping material that mainstream Hindi films provided him, he might easily have constructed the whole book around tongue-in-cheek descriptions of costumes, props and villains' lairs—such as this one from his account of the 1978 Azaad: 'The Machine of Death includes dozens of swinging spiked balls arrayed around a lava pit like a deadly game of Skittle Bowl, a tunnel lined with spinning buzz-saw blades on sticks leading to a giant industrial fan with saw-toothed blades, and a cavernous hall that shakes, dislodging hundreds of empty glass bottles to shatter down on whoever passes through. This […] strikes me as potentially being extremely troublesome to set up again once sprung.'

But he also tries to understand the workings of the Indian film industry, the sort of viewer it was reaching out to, the nature of the star system, even the sociological underpinnings such as the discontentment in the country around Emergency time. He identifies the many foreign influences on these movies—from the Spaghetti Western to James Bond—but is aware of the Indian storytelling traditions that allowed a film to change its tone as rapidly as the hero and heroine change clothes in musical sequences, so that even a Dirty Harry or Godfather copy (Khoon Khoon and Dharmatma respectively) might have songs and slapstick comedy. And he understands that this cinema was designed to be a dream factory, 'with dazzling fantasies of escape', but also had to ensure that prescribed standards of morality were upheld (a paradox that helps explain why all those spectacular villains' dens—and the vamps dancing in them—needed to be marvelled at but also destroyed in the end).

Stadtman casts his net wide, writing about those cornerstones of the Bachchan era, Zanjeer and Deewaar, but also a much less seen Amitabh film, Besharam; stylish, big- budget epics such as BR Chopra's The Burning Train and Feroz Khan's Qurbani, as well as films with more modest ambitions such as the Shashi Kapoor-starrers Chor Machaye Shor and Fakira. Some of the inclusions can readily be identified as cult B-movies—the Mithun Chakraborty-starrer Gunmaster G9: Suraksha, or the oeuvre of the Telugu director KSR Doss—but on the whole he stays close to the mainstream.

Plenty of tough love emerges in the process. Through watching dozens of films, he seems to have developed a genuine interest in such personalities as Zeenat Aman, Amjad Khan, even Jeevan and Dara Singh. I thoroughly approve of his Dharmendra love, by the way: he shows an appreciation for the star's combination of 'physicality and fitful soulfulness' in films like Seeta aur Geeta and Yaadon ki Baaraat, and there is evidence that he may have been able to appreciate the quieter, more introspective side of Dharmendra as seen in films like Anupama or Satyakam (which could never have been included in this book). And take this observation about Shatrughan Sinha: 'He doesn't swing between comedy and drama as other contemporary stars might. During his most bellicose moments there is instead the subtlest hint of a wink, making him a joy to watch without sacrificing the intensity of the moment.'

Nor does he hold back about the things that don't work for him. Here is a description of Randhir Kapoor's character in Ram Bharose (or possibly a description of Kapoor himself): 'He comes across as a freakishly, creepily desexualized man-child, basically Baby Huey without the diaper'. Dev Anand, pawing women young enough to be his daughters, affects Stadtman's ability to fully enjoy films such as Warrant and Kalabaaz. And of Manoj Kumar's exhausting righteousness, he says: 'It's difficult to criticize Roti Kapda aur Makaan for fear of seeming insensitive to its subject matter. But the truth is that one is aware enough of the gravity of that subject without Kumar's onslaught of flag overlays and on-the-nose monologizing—to the extent that criticizing it almost seems like a form of self-defence.'

Passages like these (or the one where he describes the Asrani and Jagdeep comic interludes in Sholay as a superfluous waste of time) are gladdening, because they indicate that Stadtman isn't patronising these films. He is according them—the bulk of them, at least— the dignity of analysis. He is applying standards of criticism to works that many people (including many Indians) sometimes dismiss as being criticism- and analysis-resistant.

I had a gripe about some of the inclusions. The musical Hum Kisi se Kam Nahin, the affable thriller Victoria No 203, the family social Dil aur Deewaar and the cross-dressing comedy Rafoo Chakkar in a book about 'Indian Action Cinema'? (Stadtman does clarify that 'Rafoo Chakkar is not an example of a great Indian action film, but instead a great example of how, in the Bollywood of the 70s, the elements of the Indian action film were irrepressible. Were audience expectations such by 1974 that not even a remake of a madcap American romantic comedy could be free of a sadistic villain in a Nehru jacket with a cat in his lap?')

There are a few typos, and some minor errors too. The Sholay entry tells us its success ensured 'not only that Amjad Khan would always be bad, but that Hema Malini would always be garrulous'. Neither assertion is true: Khan, despite Gabbar's long shadow, managed to convincingly play sympathetic roles not just in Satyajit Ray's Shatranj ke Khiladi but also in mainstream films like Yaarana and Pyaara Dushman—he was certainly never typecast to the degree that less personable 'specialist villains' like Ranjeet or Shakti Kapoor were. And Malini rarely played someone as chatty as Basanti again; instead she settled deeper into dignified, imperial-beauty parts as she headed towards matrimony.

Also, it may be a bit much to refer to Abhishek Bachchan as a superstar. Or to call Dharmendra's son Sonny (sic) 'an aspiring action hero' when he has been in films for 30 years. But these little things can be forgiven.

As an outsider, Stadtman had to make his peace with the episodic form of mainstream Hindi cinema—its mixing of disparate moods—and it almost feels like these tonal shifts made their way into his own writing. In a piece about Manmohan Desai's Parvarish, he goggles at the 'action scene' in where a bathtub toy pretends to be an actual submarine (complete with a bobbing plastic doll pretending to be Tom Alter, if my memory serves me right)— but also makes a serious observation about how this film, by coming down on the nurture side of the nature-nurture debate, is a bit of an outlier in a Hindi film universe where family ties have a mystical quality.

Stadtman should know about that last bit—he is part of the Bollywood family now. This book is the locket fragment that helps him prove he is a lost-and-found sibling to us homegrown fans.

(Jai Arjun Singh is the author of Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro: Seriously Funny Since 1983)