The Great Indian Table

WHAT MADE ANDHRAS FALL IN LOVE WITH TAMARIND AND RED CHILLIES

Tamarind, together with tomatoes and raw mangoes, imparts sourness to Andhra dishes. Its flowers and leaves are curried, its seeds ground into a flour, and ripe tamarind fruit is mixed with gur (jaggery) and eaten as a sweet. It is also mixed with sugar and salt to make a drink. When people in parts of Andhra Pradesh started to replace tamarind with tomatoes hundreds of years ago, entire villages began suffering from fluorosis, a disease that causes permanent damage and deformity to the bones. The drinking water proved to have high concentrations of fluorine, the effects of which are mitigated by tamarind.

According to a legend, there was once a severe famine in the area and the only plants that grew were red chillies, which then became a staple of the Andhra diet. Andhra cuisine is reputed to be the hottest in India. The hottest chilli is called koraivikaram, meaning ‘the flaming stick’ in Telugu. A dry chutney is made by pounding these chillies to a fine powder and mixing it with tamarind pulp and salt. The state’s most famous dish is a green mango pickle called avikkai, which is so hot that it has sent many an unsuspecting visitor to the hospital.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

INDIAN APPROPRIATION OF THE ENGLISH TABLE

Culinarily, the Anglo- Indian community is as diverse as its genetic stock. The vindaloo of the Anglo-Indians in the original capital of the Raj, Calcutta (now called Kolkata), is cooked in mustard oil (influenced undoubtedly by their Bengali or Bihari ancestry) and tastes very different from the Goan original. The former, likewise, would be loath to eat food with coconut milk in it; though for those living in the old railway colonies of south India, or in the Kolar Gold Fields or in Fort Kochi, it was an everyday part of the culinary repertoire. What the Anglo-Indians in Calcutta called ‘kofta curry’ was popular as ‘meatball curry’ in the South; the devilled fries of the South are more famous as the ‘jhalfrezi’ of Calcutta. And the yellow rice of Calcutta was as popular in Anglo-Indian homes up East as coconut rice in the South.

Frank Anthony (1908-93), the foremost leader of the community and its nominated representative in the Constituent Assembly and, thereafter, in eight of the first ten Lok Sabhas, offered a taste of the Anglo-Indian table in his otherwise political tract titled Britain’s Betrayal of India: The Story of the Anglo- Indian Community (1969). “Breakfast was essentially an English breakfast— porridge, eggs and fruit,” Anthony recounted. “Lunch was Indian, or what was, in fact, typically Anglo-Indian. In some homes, after the soup there was the usual curry and rice, vegetables, and fruit or a sweet afterwards. Dinner was something along the English pattern: roast, stews and pudding.”

AUBERGINE: SEER’S DIKTAT, EMPEROR’S REPAST

The author of the Kshemakutuhalam, a Sanskrit treatise in verse written around 1555, considers aubergine to be the king of vegetables. Gyanendra Pandey writes: “Fie on the meal that has no aubergine. Fie on the aubergine that has no stalk. Fie on the aubergine that has a stalk but is not cooked in oil and fie upon the aubergine that is cooked in oil without using asafoetida!” Aubergine cooked with onions, ghee and spices is one of the 30 dishes named by Abu’l-Fazl as served at Emperor Akbar’s court.

DECODING BENGALURU’S ‘MILITARY HOTELS’

An unusual legacy of military hotels survives from the period when Bengaluru was an important military hub for the training and recruitment of soldiers: their evolution is attributed to the demand created for meat-based dishes by soldiers. Typically, these tiny eateries serve a selection of village-style dishes such as dose and kal soup (goat or lamb trotter soup); ragi mudde (large, densely textured cooked balls of finger millet dough) and mutton curry; thale mamsa (goat’s head curry); and bheja fry (spiced goat’s brain). The Shivaji Military Hotel established in 1908 is well known for its mutton donne biryani, named after the areca nut palm leaf cups in which it is served.

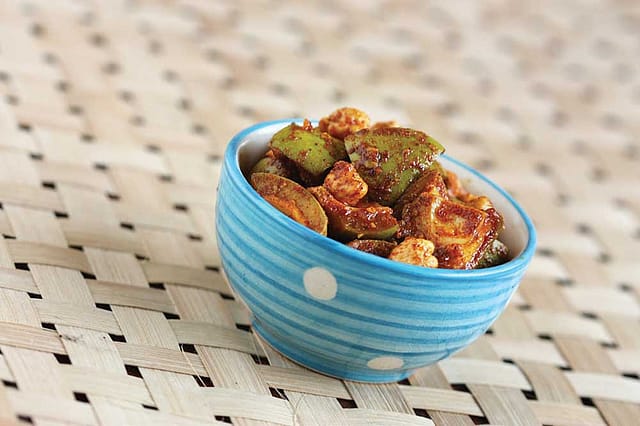

BIKANER MAHARAJA’S TEATIME MUNCHIES

Tansukh Dass Agarwal is said to have first started producing Bikaneri bhujia in 1869 (his descendants, though heading different companies, continue to control the US$1 billion-plus business). The bhujia attained its elevated status after the Bikaner ruler, Maharaja Shri Dungar Singh, adopted it as the snack of the royal court in 1877. It was, in fact, originally called the ‘Dungarshahi bhujia’ in honour of its royal patron, who served it with great pride to courtiers and visitors.

The use of the drought-resistant moth dal, which grows in abundance in and around this region, separates Bikaneri bhujia from other similar snacks made entirely from chickpea flour (besan). The other ingredients, apart from red chilli and black pepper powders, include up to 20 per cent chickpea flour as well as powdered cloves, dry ginger, cardamom, cinnamon, mace and nutmeg. The bhujia are fried in cottonseed or peanut oil.

THE ‘DUCK’ THAT IS ACTUALLY A STINKY FISH

How the Bombay duck got its name is a mystery. One theory is that the name comes from the way the fish swim near the surface of the water, like a duck. Another is that during the British Raj, the Europeans couldn’t stand the smell of the fish and it reminded them of the wooden railroad cars of the Bombay Mail train. The Hindi word for mail is ‘dak’, hence ‘Bombay dak’ which transgressed to ‘Bombay duck’.

This theory, however, is unlikely as the Oxford English Dictionary dates ‘Bombay duck’ to at least 1850, two years before the first railroad in Bombay was constructed. Also, an 1829 book of poems and ‘Indian reminiscences’ by Sir Toby Rendrag (pseudonym) notes the “use of a fish nick-named ‘Bombay Duck.’” Another explanation is that it is an Anglicism from the bazaar cry in Marathi: “bombil tak (here is Bombil)”.

Despite the pungent aroma, the British acquired a taste for the strong, salty Bombay duck, often serving it with kedgeree for breakfast (perhaps it reminded them of kippers), and the crispy fish crumbled over plates of curry and rice was a common accompaniment. King George V, noted for his love of curries, was especially fond of Bombay duck with beef curry.

NO ALOO-GOBHI WITHOUT THE REVEREND WILLIAM CAREY

William Carey (1761–1834) was an English Baptist missionary, polyglot, educator, campaigner for social reform and self-taught botanist who founded the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India in 1820. The Society, which has remained at its original location in Alipore, Kolkata, for 200 years, was responsible for propagating new commercial crops and vegetables (apart from ornamental flowers), notably tea (the Assam variety), coffee, cacao, potatoes, cabbage, cauliflower and peas.

Son of impoverished Northamptonshire weavers who started out as a shoemaker’s apprentice, Carey and two fellow English Baptists established their Mission in 1800 in Serampore, a Danish trading outpost close to British India’s capital, Calcutta.

Carey went on to become a respected professor of Bengali, Sanskrit and Marathi at Fort William College, the training ground of colonial officials, a position he held from 1801 to 1830. This made it easy for him to get the support of the Governor-General, Warren Hastings, and his wife. To Carey’s credit, though, he ensured that the Society stayed an inclusive organisation, perhaps the only one, where “native gentlemen should … not only be eligible as members but also as officers … in precisely the same manner as Europeans.” Rabindranath Tagore’s grandfather, Dwarkanath Tagore, was one of the Society’s earliest Indian members. A prominent ‘native gentleman’, Raja Radhakanta Deb, donated 500 acres to it.

Moving along the path laid by its founder-president (Carey held the position till 1824), the Society introduced new and improved varieties of artichokes, asparagus, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, carrots, cauliflower, celery, peas and tomatoes from Europe and the Cape of Good Hope; grapefruit from Florida; pummelo from Java; and seedless lychee from China. It introduced English potatoes in 1832—the Nainital and Shillong varieties today owe their origin to these imports.