The First Draft

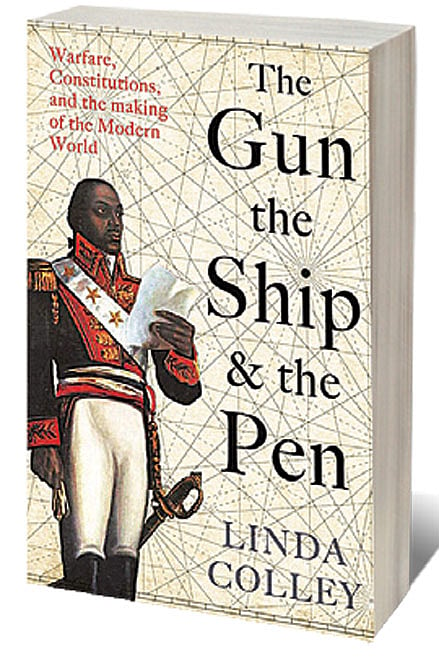

A NEW BOOK BY Linda Colley is always a major historical event, usually with a novel argument, based on several years of painstaking research, but presented in the most readable prose. Her previous works have included the making of British nationhood and the competition between Europeans and rival empires. This present work, is no exception, with its hugely ambitious global scope, meticulous source references and highly original thesis.

Colley takes as her subject the usually dry and uninviting role of written constitutions, but she turns it into a surprisingly suspenseful tale of unexpected encounters. Her central argument is that constitutionalism, long assumed to be the product of Western democracy, was closely related to the growth of modern, largescale, especially naval, warfare, the high costs that entailed and the consequent need for aspiring military powers to seek constitutional legitimacy with the citizens they were taxing.

As Colley reminds us, rules of government are as ancient as the code of the emperor, Hammurabi, in 1750 BCE. But it was from the eighteenth century on that written constitutions began to be seen as a trademark of modern, progressive nationhood. This book begins by exploring the most famous examples of the American and French constitutions, both forged in the aftermath of major revolutionary wars. It goes on to examine their impact on the rest of the world, with the many global crosscurrents in constitution-making, especially in the much-neglected constitutions of regions as diverse as Russia, Japan, India and the Pacific islands.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Colley quickly lays to rest the assumption that constitutions belonged only to republics replacing monarchies. She reminds us that, until 1914, most states adopting constitutions were still monarchies. ‘Drafting and publishing a written constitution,’ she writes, ‘supplied governments with a means to legitimise their systems of government anew. It made available a text by which to rally wider support and justify expanding fiscal and manpower demands.’

In the analysis of the 19th century German sociologist Max Weber, this amounted to a deal in which regimes offered their male subjects voting rights in return for military service, a contract which excluded women until well into the twentieth century. It was no coincidence that these paper contracts spread rapidly with growing literacy and that the print revolution turned them into a powerful, mass-oriented political technology.

‘Written constitutions,’ Colley reminds us, ‘have been as much to do with enabling varieties of power as they have been with restricting power.’ A little-known example she examines is the Nakaz of Catherine the Great, the dynamic, modernising German princess who seized supreme power in a coup d’état to become Empress of Russia. Starting in 1765, the third year of her reign, Catherine worked on this text most mornings for over 18 months, rising regularly between 4 and 5 o’clock, and reputedly developing headaches and eye strain as a result. Her completed Nakaz contained 22 chapters and 655 clauses; and, while she worked alongside a secretary, Catherine herself selected and organised the material and wrote out the finished version. Though not a formal constitution, the Nakaz was a Grand Instruction setting out rules of governance for her officials, designed to modernise her sprawling empire, though retaining sovereign power in her own hands.

Catherine’s Nakaz was printed in large quantities, circulated to the Russian provinces and made the subject of a Legislative Commission she summoned, elected by landowners, some of whom were actually female, unlike their French and American contemporaries. Although Catherine eventually abandoned her plans for greater democratisation, the Nakaz drew on the Enlightenment ideas of French philosophers and in turn influenced constitutionalism elsewhere.

By 1800, the Nakaz had appeared in at least 26 editions and 10 different languages, with extracts printed in newspapers and magazines in many countries. Its influence was felt in neighbouring Prussia and Sweden, which both adopted monarchical constitutions. Even Britain, which has succeeded in maintaining the world’s most successful, unwritten constitution, adopted and promoted the feudal Magna Carta, limiting royal power, as its founding text.

By the 1790s, this new political technology had become so popular that publishers were producing omnibus editions of constitutions, marketed to politicised, literate masses across the world. ‘Politicians, lawyers, intellectuals and soldiers,’ says Colley, ‘engaged in drafting a new constitution, along with private individuals wanting to imagine one, were increasingly in a position to pick and mix.’ One newspaper in revolutionary France even printed a template for do-it-yourself constitution-writers, suggesting suitable headings and leaving blank spaces for enthusiasts to fill up with their own reforming ideas.

The Napoleonic Wars greatly accelerated this process by destroying and re-fashioning so many European polities. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Spain, where war and revolution produced the famous Cádiz constitution. Though short-lived, it was a model of limited monarchy and parliamentary government that inspired reformers across the globe, including our very own Raja Ram Mohan Roy. The collapse of Spain’s colonial empire also unleashed a wave of new constitution-making in South and Central America, often modelled on the US up north.

An interesting fallout from developments in Spain and South America was their impact in India on the Calcutta Journal, published through the 1820s by Roy and his ally, the British maverick intellectual James Silk Buckingham. United by the aim of reforming the government of the East India Company, this unlikely couple met almost every day for breakfast and carriage drives in colonial Calcutta to discuss their projects. Their journal reported constitutional developments across the world and especially in South America, with its growing enfranchisement of native populations.

This is just one of the many very human stories Colley interweaves across this monumental work. In its pages, we meet characters as diverse as the Utilitarian British philosopher Jeremy Bentham, designing constitutions to order for newly independent Greece and Venezuela; to Simón Bolívar, the liberator of former Spanish colonies, drawing liberally on British and American models; to potentates like King Kalakaua of Hawaii and the Bey of Tunis, struggling to modernise their ancient kingdoms. Many of their efforts proved transient. According to one estimate, at least 77 constitutions were implemented in South America between 1810 and the early 1830s.

By contrast, the most stable and enduring of the world’s constitutions was the unwritten Westminster model, with its Mother of Parliaments. Colley traces this British exceptionalism back to its early roots limiting royal power, its later naval supremacy, its global empire and the strength and stability of its fiscal and financial institutions. But the unwritten British model of constitutional monarchy and parliamentary sovereignty influenced written constitutions everywhere from Belgium and the Netherlands to even the remote Pitcairn Islands of the Pacific, populated by the descendants of British mutineers.

A prime site for British-inspired constitutionalism was, of course, colonial India. Colley reminds us that, as far back as 1895, Congress leader Bal Gangadhar Tilak had launched a Swaraj Bill, aiming at Home Rule for India within the British Empire, with a bicameral parliament under the British Empress. Forty years later, the Westminster Parliament itself enacted a very similar model with its Government of India Act. Our 1935 constitution introduced provincial autonomy, with provincial ministries democratically elected by 30 million newly enfranchised voters. The federal clauses of the Act, though never implemented, went even further in providing for a central government responsible to a bicameral legislature, if only Hindus, Muslims and the nominally autonomous princes could agree to join. Though overtaken by the outbreak of World War II, this 1935 colonial constitution, Colley reminds us, ‘would go on to shape two-thirds of the content of the Indian independence constitution of 1949–50, the post-colonial world’s longest surviving constitution’.

Surveying the role of constitutions in polities as diverse as 19th century Hawaii and Tunisia, on the one hand, to White settler states like the US, Australia and South Africa, on the other, Colley concludes that constitutions could be a double-edged sword, both attempting to fend off Western dominance for some, while seeking to legitimise newer White Dominions. The most successful example of the former was the Meiji restoration in late 19th century Japan, with a constitution that managed to combine the divine right of emperors with modern parliamentary democracy, an example much publicised in India, where it helped inspire Tilak’s prototype.

Constitutions, of course, are only as powerful as the political will to implement them. The prime example of a paper constitution never implemented was the one Stalin commandeered in 1936 for his Soviet dictatorship. ‘Even as I write,’ says Colley, ‘populist, authoritarian, would be authoritarian, repressive and corrupt governments are flourishing and multiplying across continents, for all the wide availability of written constitutions.’ But she sees even such paper exercises as offering a useful text to which democratic reformers often can and do turn. She singles out the example of the liberal 1993 Russian constitution, still inspiring human rights campaigners against Vladimir Putin’s brutalities.

This book ends appropriately with a moving photograph of the young protester Olga Misik holding up a copy of the Russian constitution as she demonstrates on the streets of Moscow in 2019. It’s an image which might even inspire some in India today to resist theocratic assaults on our own constitutional rights.