The Fellowship of Four Friends

WHEN ONE LOOKS back at the Subcontinent in the first half of the 20th century, two broad interpretive themes dominate the writing of its history: the “high politics” of its march to freedom from colonial rule under leaders and, more recently, “subaltern” versions of that history. There are other interpretations as well with an entire industry being in existence almost from the time of Independence.

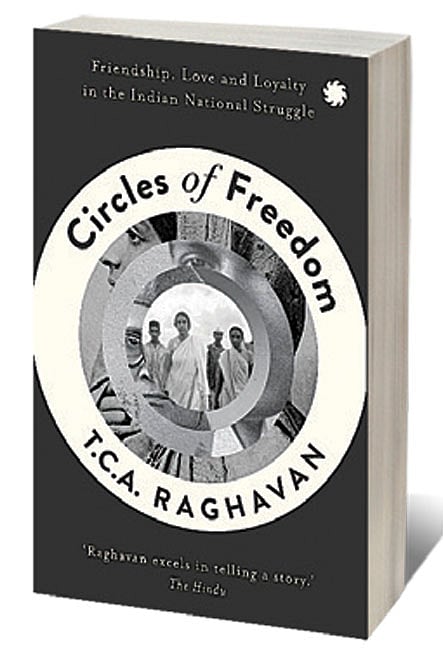

Is there room for more interpretations and perhaps, a fresh look at that period? TCA Raghavan, a former High Commissioner to Pakistan and a historian, now tells that story from a more intimate vantage, that of friendship between four friends during the decades that preceded Independence. In Circles of Freedom: Friendship, Love and Loyalty in the Indian National Struggle he describes the bonds forged between Sarojini Naidu, Asaf Ali, the journalist and diplomat Syud Hossain, and the politician from Bihar Syed Mahmud. The protagonist of the story is Asaf Ali, who was born in an old Muslim family of Delhi. Three of the four characters, Naidu, Hossain and Asaf Ali met in London in 1913 and their friendship continued after Independence. Muhammad Ali Jinnah was another character in the cast but it is tough to describe his role: he was a friend to them but by the end he was more akin to an enemy. In many ways this was a microcosm of what transpired, during those decades, to India at large.

This is a novel way of telling history from the vantage of a single emotion, love. One can question whether that single emotion can capture the vast panoply of events and personalities of those decades. But Raghavan’s threading is interesting and seamless. There’s Sarojini Naidu, a bon vivant from 0Hyderabad who is trying to build bridges between Hindus and Muslims; then there is Asaf Ali, who is training as a barrister but who really wants to enjoy poetry and wants a slice of public life, and then there’s Jinnah, allegedly the “ambassador of Hindu Muslim unity” but in the end a bitter man who gets what he wants, but by creating all-round mayhem.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

It is interesting to speculate if friendship could have altered the course of history. The trouble is that all members of the cast were on one side— Indian nationalists—while events went the other way under the malevolent spell of Jinnah and others, but especially Jinnah. But what matters in the end is the process: the attempt to forge a new nation, the efforts to keep it united and the forlorn hope of preventing religious divisions. One could also say that friendship did not prevail and that, in any case, politics rests on a distinction between friends and enemies and so the idea was doomed.

Raghavan tells Asaf Ali’s story in fine detail: from his encounter with Vinayak Damodar Savarkar in London in 1909; his getting sucked into being an informant—unwittingly—for the colonial government, something that gave him grief for a long time and his involvement in Indian nationalism. His participation in the defence of INA soldiers during their trial is a well-known event of India’s freedom struggle. Asaf Ali’s life represents the modal journey of a “nationalist Muslim.” In contrast to radicals like Mohammad and Shaukat Ali, men like Asaf Ali did not tip religion over nation in their lives but neither did they abandon religion over politics. This was probably the source of so many complications and continues to be so until today.

The fellowship of the four friends survived all the way to Independence and beyond. But that event did not generate the expected joy for the four in particular and the aftermath was bittersweet. Naidu was the governor of United Provinces (as UP was known then) when the liberation of Hyderabad took place in 1948. Her recollections of that event are not known. One can speculate the event could not have been happy for her. She had, after all, been a part of Hyderabad society if not its elite. She died in March 1949, just months after Operation Polo. Less than a week before Naidu died, Hossain, too, passed away in Cairo where he was serving as India’s ambassador to Egypt and is buried in Cairo. Mahmud became a minister of state for external affairs under Nehru until 1957 when he quit due to failing health. He lingered on until 1971.

Perhaps the most painful end in Raghavan’s telling was that of Asaf Ali. He became India’s first ambassador to the US but had to face headwinds right from the start of his appointment. Nehru described him as “a somewhat ineffective person” in a letter to Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit just a day before his appointment was announced. His tenure in Washington DC was filled with intrigues against him, both in India and by his subordinates in the US. There were multiple pressures: He was expected to follow “Gandhian norms” even as he was to be an effective diplomat, a contradiction in terms. It was also a confusing time: the British had gone but Indians were yet to find their feet. He lasted a year as ambassador. By then, his marriage to Aruna Asaf Ali had broken down and she did not accompany him to the US even after Mahatma Gandhi urged her to do so. He died in harness as India’s ambassador to Switzerland in 1953.

In these polarised times—when the friend-enemy distinction is as stark as it can get—one can only look back with sadness at the fate of “nationalist Muslims,” a term that seems oxymoronic today. Maulana Azad, Asaf Ali, Rafi Ahmed Kidwai and a host of others served India to the best of their abilities. But that was not enough. They were routinely castigated by Jinnah as enemies. His favourite expression for them was “Congress’s show-boys.” In one incident narrated by Raghavan from 1946, once when Hossain called Jinnah, Naidu and the others heard the receiver at the other end being put down (“banged down” to use a contemporary expression). When Naidu asked him what happened, Hossain said Jinnah described him as “being in the enemy camp.” This was after decades of friendship with the qaid (leader). Jinnah’s behaviour with Asaf Ali was worse and exceptionally petty. In 1934, Asaf Ali was elected a member of the Central Legislature. Jinnah, too, was a member. But when he invited members of the legislature to his home for a tea party, he purposely kept Asaf Ali out.

In the end, Jinnah got what he wanted: a separate country but one that continues to struggle with nationhood to the present moment. He was also vain: he purposely chose to be Pakistan’s first Governor General and not its Prime Minister. That way he would rank above Nehru and be at par with Mountbatten, India’s first Governor General after Independence. All manner of historical justifications have been proffered for that step but in the end it was an exercise in vanity. It led to grave consequences for his country: prime ministers became mere pawns in power games beyond their ken and control. Pakistan has never really recovered from those mistakes at its origin. Its fate continues to be under a question mark.

While the life of the four friends had its share of trials and tribulations, history will remember them kindly even as the qaid’s choices are now openly questioned in the country he helped birth. Raghavan tells the story gently and with the sensitivity that it deserves.