The Fall of the Dosa King

IT HAD BEEN an exceptionally rainy month and Kodaikanal was cooler than usual for the time of the year. As Murugesan and Raman, two guards in the Tamil Nadu government’s forest department, patrolled their beat on the winding ghat road that goes from Perumal Malai to Kodai town mid-morning on 31 October 2001, there was a constant drizzle, with mist rolling in and out and the scent of wet wood hanging heavy in the air.

The two men kept their eyes on Tiger Shola, a dense grove downslope from the road. Shola (or cholai) are forest patches of native deciduous trees, shrubs and grasslands unique to the Nilgiri Hills in the southern Western Ghats. Kodaikanal, located in a spur of the Western Ghats projecting eastwards into Tamil Nadu, is at an elevation of 2133 metres. It is a hill resort-town established by the British in the nineteenth century. Its untidy expansion over the decades is the story of every ‘hill station’ in India. But the shola around Kodai are still magnificent, painting the slopes and the valleys in every shade of green, the trees with their thick trunks and gnarled branches, and the vines twisted over and around them testimony to the age of the forest. The Kodai sholas are even known to have tigers. Long ago, someone spotted the big cat in this stretch between Perumal Malai and Kodaikanal. That is why it is called Tiger Shola, though no one remembers when anyone last saw a tiger there. Still, there was no telling. It could always be that kind of day. In any case, so much else happens in a forest that a forest guard has to keep track of. The place was teeming with bison and elephant herds, bear and wild boar.

Every day, the two guards had to report back to the Forest Office in Kodaikanal any animal activity, usual or unusual. Or for that matter, any human activity, which in those thick woods usually meant trouble: illegal tree-felling, also tourists going close to the gaur, only to discover they are not placid buffaloes and could give chase if provoked. Raman kept an official diary in which he noted down the day’s happenings.

Keeping close to the wall on the ghat road, the two guards had barely crossed the fourth mile post from Perumal Malai when Raman stopped in his tracks. Something — someone — was lying in the undergrowth some five metres below, but there wasn’t a clear view from the road. He and Murugesan swung over the low parapet and, sure-footed in the way that foresters are, made their way down the wet, slippery slope.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

It was a young man, and he was dead. He was lying on a patch of thick grass. New vegetation had grown around him, obstructing a clear sighting from the road. His face was bloated. The clothes suggested to Raman and his colleague that this lad had been better paid than them. Perhaps he had even been to a good school and college. In his blue checked shirt and sandal-coloured trousers he looked very much a city boy. Unidentified bodies in the jungle were not an everyday occurrence in Kodai. But there was always the possibility of a jilted lover leaping to his death, or some unfortunate tourist being attacked by a bear.

Perumal Malai today is a messy, bustling town in its own right, with homestays and guest houses for budget tourists who find Kodai too pricey. The roadsides are packed with parked cars, mini buses and small load-carriers. Crowds of youngsters go trekking up to the Perumal Malai peak, taking selfies along the way. Back in 2001, though, Perumal Malai was a small village on the Palani Ghat road to Kodai — small enough that everyone knew everyone else.

The foresters, who were also from Perumal Malai, asked local passers-by if anyone knew the man, just to rule out that he was a local. He did not look familiar. They then asked a villager to fetch Natesan, the local fireman. By the time Natesan arrived, it was 12.30 p.m. The two foresters left the fireman to guard the body and headed to the Forest Office, getting a ride in a vehicle going to Kodai. There, a senior officer told them to inform the police.

IT WAS AROUND 6.45 p.m. that the two foresters returned to the spot where the body was still being guarded by Natesan. Sub-Inspector Emmanuel Rajkumar and Head Constable Sebastian from the Kodai police station were with them. Also with them in the police jeep were two sanitation workers, Sailathnathan and John, described in police records as ‘scavengers’, the most polite word that officialese could come up with to refer to members of a caste group that was associated with society’s ‘impure’ tasks. No one else would touch the body because they belonged to castes that looked down on these jobs. Though it was pitch-dark, a small crowd of local people had gathered at the spot. Head Constable Sebastian, who had brought his own camera, shot a full reel of eight frames of the body and the area where it had been found. He also made a sketch of the scene. A case under Section 174 of the Criminal Procedure Code (Cr.PC), which empowers the investigating officer to ascertain the cause of death, had already been filed at the Kodaikanal police station on the basis of Raman’s complaint.

Sailathnathan and John took the body to the government hospital in Kodaikanal. Two days later, on 2 November, Dr Sivakumar at the hospital conducted the post-mortem and arrived at the following conclusions:

‘Time of death: approximately three to five days prior to autopsy. Death due to asphyxia on account of throttling.

Male body, aged about thirty years. Nails on both fingers and toes blue. Face, chest, abdomen, scrotum and penis slightly bloated, as the body was in the early stages of decomposition. Eyeballs and tongue bulging out. Contusion in the front and outer aspects of the right shoulder. Fracture of the greater horns of the hyoid bone, the U-shaped bone located in the neck just over the voice box that holds the tongue in place.’

The post-mortem made it clear the man had been murdered. But there was a problem. The body had not been identified. It was already more than forty-eight hours since it had been found. The police had received no missing person complaint. With their small staff and resources, the Kodai police appeared to have decided it was pointless to launch a murder investigation that might linger as an unsolved crime in their precincts. But they did not close the case. From their point of view, they had carried out all the procedures correctly — taken photographs of the body and preserved the clothes and other personal effects found on the man. There was nothing more to be done. On the same day, the police had the body buried in the Hindu ‘burial ground’ maintained by the Kodai municipality.

But the police officers had foresight enough to know that someday someone might come looking for the body. They got the watchman at the cemetery to place a large granite stone to mark the grave. If there was to be a further police investigation and the body needed to be located, it could be found easily.

NONE OF THE people involved in this chain of events over those two wet days in October-November 2001 knew the importance of what they had stumbled upon. But very soon it became clear that Raman and Murugesan’s discovery, and the procedures followed by the foresters, the police, the doctor and the men who buried the body, would form the main evidence in a murder investigation that spanned eight districts of Tamil Nadu and had to pass three trials at three different levels of India’s judicial system over a period of nearly two decades.

The accused was Tamil Nadu’s most well-known restaurateur, who ended up scripting a criminal coda to his own remarkable humble-beginnings-to-hubris story. That story may have ended differently had the body of the young man never been found, had it rolled right down the slope and plunged into the thickly wooded gorge a couple of hundred feet below, where a stream flowed fast, fed by the nearby Silver Cascades waterfall. For the killers of Prince Santhakumar, that had been the plan. But a shelf-like projection on the slope broke the fall of his body as they threw it out of their Tata Sumo. And as the body lay there, waiting to be found by forest guards Raman and Murugesan, the clock started ticking for Pitchai Rajagopal, founder of the celebrated restaurant chain Saravana Bhavan.

WHEN PITCHAI RAJAGOPAL first left his home in the village of Punnaiyadi as a thirteen-year-old in 1960, all he aspired to was to work as a salesman in a grocery store in Chennai, the kind of job that many other village boys had managed to get in cities such as Coimbatore and Salem. Three decades later, Rajagopal had become a leading restaurant baron, the founder of Hotel Saravana Bhavan, the man behind Brand HSB, hailed across Tamil Nadu as the leader of a new generation of Tamil entrepreneurs in an economically emerging, post-liberalisation India. By the early 1990s, the ‘high-class’ vegetarian fare in his restaurants, the stories of his uncompromising insistence on quality and his generosity towards his employees had become legendary, attracting clientele and jobseekers alike.

When his success story was being serialized in the Tamil magazine Junior Post in the late 1990s (published in 1997 as his autobiography titled Vetrimeedu Asai Veithen and in English as I Set My Heart on Victory), a reader wrote asking: ‘What were your goals in your young age? Have you achieved them?’

Rajagopal, known by then as Annachi (or elder brother), replied: ‘I had never thought of doing a particular business or attaining a good position in life. I only thought, even in my young age, that I should work hard, whatever work I did.’

Punnaiyadi itself was a place of modest ambitions, a village of about ninety households, almost all belonging to the Nadar agricultural caste group that had over the years transitioned to trade. It lies in the hinterland of Thoothukudi district, forty-five kilometres from the coastal town of Thoothukudi, the district capital. Leaving behind the blue waters of the placid Gulf of Mannar at Thoothukudi, the road to Punnaiyadi winds and curves past salt pans, paddy fields, little towns and villages, past scores of small wayside temples painted in multicoloured hues and an equal number of churches.

Thoothukudi is a semi-arid, drought-prone district in the rain shadow southern zone of Tamil Nadu. Though the perennial Thamirabarani river — the only river that originates in the state, high up in the Pothigai Hills — flows through Tirunelveli and Thoothukudi before draining into the Gulf of Mannar, its water management has traditionally been poor, and people are dependent on the north-east monsoon for farming and for replenishment of their village tanks and wells. Natives of the area describe their land as vaanam pattriya bhoomi— land that looks towards the sky.

At the time the teenaged Rajagopal left home to find a job, agriculture had become a constant struggle in that arid region, and young men from Punnaiyadi and the villages around were leaving to find jobs in Tamil Nadu’s capital Madras, as it was then called, and other cities in the state.

Toddy tapping had been the traditional occupation of the Nadar caste, but by the late nineteenth century the Nadar men had made their mark as a mercantile community with an immense capacity for hard work. Nadar traders specialized in two kinds of retail trade— stainless steel vessels, which are used in most Tamil households, and small grocery shops or provisions stores known as malige kadai. The community is politically influential. Kamaraj, the powerful Congress chief minister of Tamil Nadu, was a Nadar who had himself worked in a grocery shop as a teenager. Southern Tamil Nadu has produced other famous Nadars — Shiv Nadar, the industrialist and founder of HCL, was born not far from Punnaiyadi, in Tiruchendur; and the late Sivanthi Adityan, Shiv Nadar’s maternal uncle, who was a media baron.

It had become the norm for Nadar men to leave the village at a young age and carve out their destiny elsewhere, and Rajagopal was no different, trying his luck at different places and in different jobs. He detailed those experiences in his autobiography, a self-promoting account of himself as a saint-entrepreneur fired by a divine call to action for a larger good. For a long time, it was distributed free at Saravana Bhavan restaurants as an inspirational rags-to-riches story.

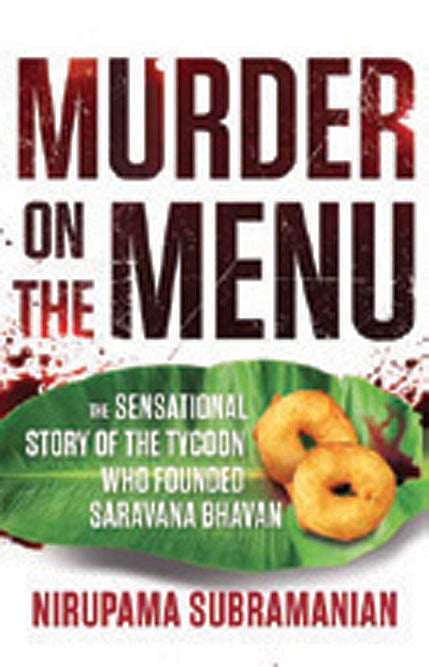

(This is an edited excerpt from Murder on the Menu: The Sensational Story of the Tycoon Who Founded Saravana Bhavan by Nirupama Subramanian | Juggernaut | 208 pages | Rs 499)