The Allure of the Anti-Hero

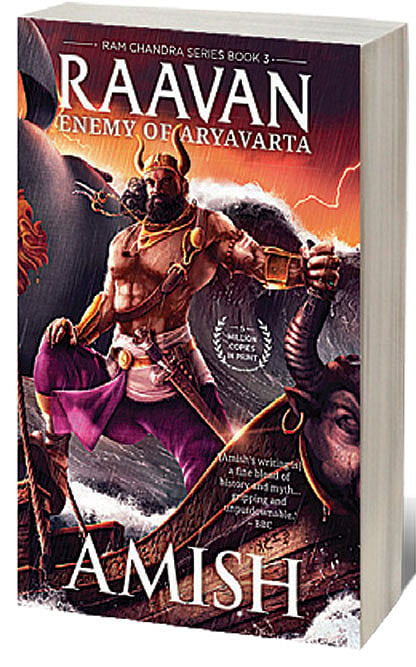

IN THE THIRD of his five-book Ram Chandra Series, Raavan: Enemy of Aryavarta, Amish Tripathi explores evil, situating it in the character of Raavan. Here he unsheathes Raavan’s core personality that is dark enough on its own. But this darkness spills over into darker shades of black when destiny writes out his path using crayons of self-preservation and revenge. Raavan is arguably the most complex villain in Indian literature, and Amish delivers one of the kind we have never met, re-imagining evil in ways we have not known.

The continuum of this great saga matches Amish’s commentary on modern India. Weaving familiar characters and their stories, he uses ancient time-space landscapes to deliver modern-day lessons. From independent India’s relentless contempt for wealth creation and the choking hold of bureaucracy on its people in general to the exploration of the recent Sabarimala controversy in particular, Amish continues with his bigger motive: to make India ‘worthy of our ancestors once again’.

Evil, as students of Indian philosophies know, is not a judgement. Indian thought rejects political tools such as heaven and hell, believers and non-believers, or even a god that punishes, which forms the essentials of Abrahamic faiths. Here, among the several underlying layers of philosophy one stands tall: Dharma, itself an abstraction that changes from one being, one situation, one karmic expression to another. Such complexity of thought is impossible to turn into commandments, dictums, dogmas.

In Amish’s darkest work so far, Raavan captures this subtlety and takes you on a rollercoaster of compassion and fury, love and rage, strategy and spontaneity. Barring the accentuated edges, we discover in ourselves a few shades of Raavan’s darkness. We move with his ambitions, weep in his grief, flow with his faith, celebrate his revenge, baulk at his brutality, judge his retributions and get startled at the climactic ironies of fate—we are wonderstruck at Amish’s craft of storytelling. Each reader will view Amish’s Raavan in her own way, even as she will explore the several Raavans within.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The pace of the book varies with the depths to which Amish explores situations that give us windows with which to view Raavan. One of the longest and most intense sequences in this tension-filled and Amish’s most violent book focuses on the flame of light burning within Raavan. You can literally see how Raavan’s pursuit of Vedavati is transforming him, bringing a flicker of light here, a ray of hope there. From the physical to the philosophical, the discourse between the two, both silent as well as verbal, is beautiful, gentle, calming—a complete antithesis to what Raavan stands for. Having built the scenario, Amish is as merciless as Raavan while destroying it, brutally extinguishing all hope of any good in him. Absolutely brilliant.

Looming in the shadow of Raavan’s are other characters that will bloom in the next two books: heroes Ram and Sita, twists of a larger game being played by gurus Vishwamitra and Vashishtha, and Raavan’s son Indrajit. But above all, the one character that trails him like a shadow, physically as well as in inner explorations, is his brother Kumbhakarna, hard on the outside but gentle within, virtually Raavan’s alter ego. Again, Amish’s Kumbhakarna is unlike any we’ve seen. He is devoted to Raavan but is also his conscience; he supports him in all actions but baulks at adharma. Kumbhakarna, I sense, will be a character we will weep the most for—in the last book.

With Raavan, Amish has brought all major characters and contexts, including the war over Vishnu, to a single point. On his bowstring of storytelling, the arrow has been pulled back fully. In the next two books he will release it.