The Acrobat and the Safety Net

NARAYANA AND SUDHA MURTHY are often seen as a single entity. Here is a couple that is different but equal. Murthy is best known as the mind and mettle behind Infosys, and Sudha is one of India’s highest selling women authors. Both are at the helm of their fields. But if you look a little closer, differences will emerge. For one, the surnames are spelled differently. Sudha (and her children Rohan and Akshata) use ‘Murty’, whereas Narayana uses ‘Murthy’. The difference of an alphabet hints that reality might be more interesting than perception.

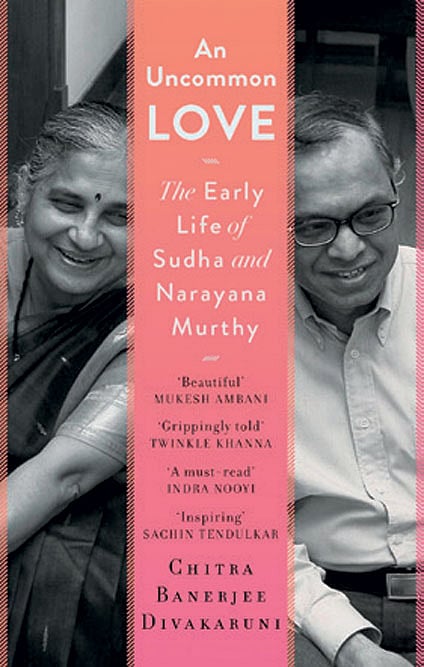

In the biography An Uncommon Love: The Early Life of Sudha and Narayana Murthy (Juggernaut; 345 pages; ₹799), Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni delves deep and far to tell us about this couple, who we know best from the news, and little of in person. Divakaruni discloses, for instance, that when the couple got married, Sudha chose ‘Murty’ as she felt that adhered more closely to the Sanskrit original. When the children were born, they got the same surname as their mother. At this time the couple also ruffled many family feathers as they insisted on a no-fuss wedding. FYI cards replaced elaborate wedding invitations. Lengthy rituals were reduced to thirty minutes. And the priest was instructed to skip over shlokas that urged female subservience. Sudha even refused the mangalsutra, pointing out that since Hindu men had no totem to reveal their marital status, why would she? However, on the last matter, she had to relent to family pleasure, and the mangalsutra was duly handed over.

In the court of public perception, Sudha is seen as the elderly woman with a beatific face, dressed in sarees, her hair in a bun, often adorned with flowers. She makes the news when she mentions carrying her own utensils and food on foreign travels, for fear of contamination. Such statements get both sides of the ideological divide clanking their ladles, and fussing. An Uncommon Love tells us who Sudha and Narayana are beyond appearances and assumptions. By choosing to focus on their early years, Divakaruni unpeels the people behind the personas. Having been granted firsthand access to the couple, this book is no scoop. Instead, as Divakaruni admits, it is a “very collaborative project”. She writes about difficult moments in their lives—Murthy’s fraught relationship with his father, Sudha’s challenges balancing home, office, and motherhood—but Divakaruni’s gaze is always parental and never critical. When the Murthys entrusted her with their story they knew they were relenting to a safe space. Divakaruni has known Sudha’s brother Shrinivas from college days and was familiar with the family. Divakaruni also has a reputation as a formidable fiction writer whose retellings of the epics, and novels with historic female protagonists have created legions of fans. Her professional standing and her personal equation with the family made her the best fit for an authorised biography.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Divakaruni, Chiki Sarkar, the publisher of Juggernaut and the Murthys decided at the start that the book would focus on their early years. “Because once Infosys goes public, their story also kind of goes public.” Divakaruni adds, “In this book we were interested in what is the root cause of their success?”

Speaking about the book’s genesis, Divakaruni says, “Right up front, we decided something; this is not going to be a biography to make them look good. This is going to be the story of a journey with all its human flaws, with its ups and downs, so that people can be inspired by it. Like when I’m writing the story of Rani Jindan (The Last Queen), I’m not portraying her as some amazing, perfect queen.She’s very much an ordinary person. She has temper tantrums. She makes mistaken decisions, but she’s also very courageous. I wanted to show them as fully complex people with good things and not so good things. They made some very good decisions, and they made some mistakes. But they always picked themselves up and walked on. That’s what I wanted to show.”

An Uncommon Love is not a “warts and all” biography, it is more “bumps and all”. It shows the personal and professional challenges of the young couple, while ensuring that their halo never dims. Sudha and Narayana (now with a more interesting backstory) remain on the pedestal. The book reiterates their ‘simple living’ like a mantra. It reminds us that behind the sheen of success lies years of struggle. It tells us that sedate elderly couples might have had a sensational past. It shows us that those who might appear traditional today might have been revolutionary in their own time. And it proves that stories of early love, young love, which defies odds, which stands on idealism and passion, makes for compelling stories and saps of even the most cynical.

When I speak to Huston-based Divakaruni I ask, having retold the epics in her previous books, which epic characters would she see Sudha and Murthy as? Amiable and genial to a fault, she pauses for long. And then replies—Sudha as Draupadi and Murthy as Ram. Murthy as Ram hardly surprises, but Sudha as Draupadi highlights that the biggest revelation of this biography is her. She comes across as no Sita, instead she is all fire and spunk. She defies tradition, follows her will, stands by her husband, and builds her own career in a male-dominated field.

In vivid detail, Divakaruni recreates their early days of courtship when they first meet in the 1970s in Pune. Sudha (Sudha Kulkarni, 24) was a jeans and T-shirt-clad young woman, with a bob cut, who wore sarees only to TELCO (Tata Engineering and Locomotive Company) where she worked as the first woman engineer. She meets Murthy (28) for the first time through a common friend. While they don’t seem to have much in common, books become their instant glue. And soon they are frequenting the storied cafes of Pune, which still exist, such as Vaishali, Rupali and Café Good Luck. While they both hailed from Karnataka, the city’s cosmopolitan nature allows them the freedom to court. While Murthy was a traveller and a reader, Sudha was a film buff, who even won a bet against friends that she could watch a movie every day, over 365 days! Her love for cinema remains unchanged and the “first-day-first-show” girl is now the “first-day-on-Netflix” grandmother.

For Divakaruni, moving from fiction to fact came with its own perils and perks. The perk was that the “plot had been handed to her” and she did not have to spend time working out the narrative arc for her characters. She says, “The challenge was different, which is from the bare bones, episodes or facts that they told me about, I really had to figure out, what does this say about them? What does this say about their inner life?” While she mostly interviewed them together, she at times also interviewed them apart. Often their telling of the same episode varied. She adds, “It really made me realise how our memory is a very slippery thing. It remembers what it wants to remember.”

A particular incident in the book, which illustrates their different versions of the same incident, occurs around the halfway point. Infosys is still finding its feet, but Murthy has now hired colleagues like Nandan Nilekani. They are caught in a crisis when the money from a US-based investor Donn Liles doesn’t arrive. Sudha tells Murthy that she can hand over her jewellery to the bank as collateral till the money from the US comes. Sudha didn’t remember the incident quite like this as she believed the jewels were never surrendered. With repeated retellings and by asking detailed questions, Divakaruni realised that the truth was in the middle. That moment was especially fraught for Murthy as it brought back memories of his mother having to pawn her wedding jewellery. For Sudha it was a question of practicality rather than sentiment. Divakaruni says, “They had a different take and I think as they talked through these things, they actually learned something about each other, maybe which they had not expressed to each other during that time.”

Like a bildungsroman, Uncommon Love also explores how the protagonist develops morally and psychologically. Sudha’s apparent rebelliousness ebbed with time. As a young man, fired by the ideas of socialism, Murthy wore his ideology (quite literally on his sleeve). He donned a red shirt—the colour of communism— to his first meeting with Sudha’s parents. Her parents were unimpressed and did not want their daughter to marry an “unemployed stubborn leftist”. It was only with her mother’s assurances that Mr Kulkarni gave his consent to the wedding.

With time of course Murthy’s left leanings changed into “compassionate capitalism”, especially after his travels in Bulgaria, which proved harrowing. As his ideology morphed, so did his demeanour. The man who was once easy-going and spent time with friends and books became a man possessed by a dream. He abandoned both books and company. Divakaruni says, “Even Sudhaji says that if she knew he was going to change so much, she might not have married him! But I think most people who achieve something extraordinary, have that passion, and have that dream. They dispense with other things that are not part of it.”

AN UNCOMMON LOVE chronicles the story of Sudha and Murthy, but it also tells a bigger story of India moving from pre to post liberalisation. In the late 1970s starting a company was akin to walking in a bog of permits and licences. Murthy had to travel from Pune to Mumbai to use a computer for 15 minutes in the middle of the night. An hour of computing cost `550. His biggest challenge initially was access to fast computers, as the import of US machines was nearly impossible. Murthy’s vision was that he realised fast computers were the future, even if the government refused to see it. He stuck to his entrepreneurship dream believing, “If I don’t take advantage of the software revolution right now, I’ll never produce anything worthwhile.”

The story of entrepreneurship is essential to this love story. Divakaruni says, “It’s a love story on a lot of levels. And one of them is Mr Murthy’s love for technology and for bringing that to India, and for creating a bridge between India and the US. And people forget now what it was to have a startup at that time, how difficult it was. And again, it’s not separate from the personal story because Sudha had to sacrifice a lot, so that Mr Murthy could do all the things that he wanted to do. And she said something very sweet to him, which I put in the book, ‘You be the acrobat and I’ll be the safety net.’ I thought that was so beautiful because that shows something about the partnership. It shows something about relationships. It also shows, what does a startup need? The startup needs that safety net.”

An Uncommon Love shows how Sudha could easily have been the acrobat herself. Her intellectual rigour matched both her determination and courage. She was the only woman student in a class of 150 at her engineering college in Hubli. She joined despite numerous family reservations, bolstered only by her father. The college did not have a single women’s restroom, so she would walk 45 minutes to her home during her lunch break to use the toilet. When she joined TELCO, the men overlooked her and disallowed her from entering the premises of the Jamshedpur TELCO plant. When her daughter was born in 1980, Sudha was still working with TELCO as a senior engineer in Mumbai, having risen in the ranks. But her biggest professional disappointment came when she told Murthy that she wanted to join Infosys given both her coding skills and business chops, only to be rebuffed with his statement; “The two of us cannot be in the same company.” Divakaruni says at that moment Sudha was “probably the most upset she’s ever been with him in their whole life.” But in the writing of this book, Divakaruni also realised that this moment highlighted, “Something important for us to realise is that success comes with a cost. And the cost is equal but different for the person who is having that dream and trying to realise it, and for the supporting partner.” In Sudha’s case, giving up on her engineering career led to her writing career, which only proved that “when life closes a window, it opens a door.”

Having sent off An Uncommon Love into the world, Divakaruni has already returned to fiction. But the biographer’s bug persists. She is already thinking of prospective projects. As she says, “I’m excited about writing biographies, because I’m covering the hidden story, especially of people who have a public image, but that’s not the only truth. So, uncovering the hidden story and showing them as human beings, that is what I like to do.”