Books | Best of 2020 Books

Tabish Khair

Author

Open

18 Dec, 2020

Open

18 Dec, 2020

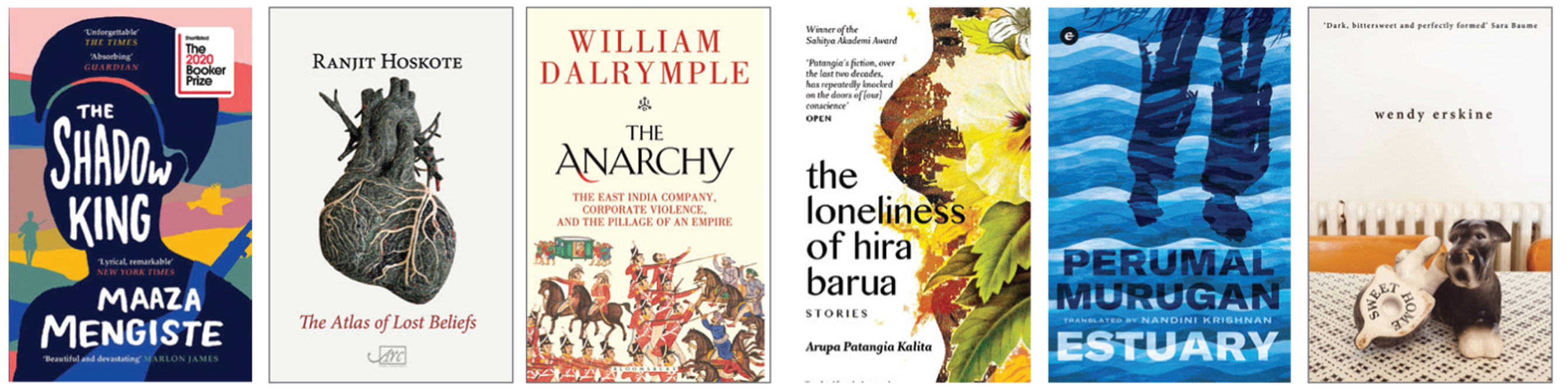

I avoid endorsing Booker-shortlisted novels. Most of them are good, but the Booker is an ‘overdorsed’ prize, and it leaves out many novels, just as good, either because they do not meet its eligibility criteria (which privilege big publishing and UK and US imprints) or for other reasons. But there are always exceptions. Maaza Mengiste’s The Shadow King (Canongate) was my exception in 2020, a year that saw a strong Booker shortlist. But, alas, it was published in 2019. That was also the case with another book I read only this year and wanted to include: William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy (Bloomsbury). Based in Denmark, I obviously run the risk of getting books just a few months too late.

Of the books I can recommend, because I read them in their year of publication, 2020, there are four that stand out in my memory. Two are collections of short stories, one a novel, and one a poetry collection. Of these four, two were translated into English in 2020, but were published earlier in the original languages.

Translated by Nandini Krishnan, Perumal Murugans’s Estuary (Eka) is an unusual novel from a writer who, after being forced to declare himself dead, has come fully alive with the years. I suppose it will be labelled ‘speculative fiction’ by those who market books. Comparisons might be made to Orwell and Kafka and Gogol, and they would be justified, but not entirely apt. Because Estuary shares just as much with RK Narayan. It presents an idiosyncratic dystopia whose dark corners hide a jester, and whose public concerns are always rooted in the small-town domestic.

In her first collection of stories, Sweet Home (Picador), Wendy Erskine is absolutely brilliant at capturing the many shades of Belfast, especially in its broken corners. She is enabled by a pitch-perfect ability to write in a language spoken by her characters. Erskine’s use of the English spoken in Belfast is something that Indian English writers can only envy, because attempts to capture Indian versions of English flounder on the rocks of the very different linguistic realities of India. Erskine writes with absolutely no pity, and with the greatest magnanimity— a very difficult act.

What struck me most about Ranjita Biswas’s translation of Arupa Patangia Kalita’s Assamese collection of stories, published as The Loneliness of Hira Barua (Macmillan), was not the gendered aspects of her engagement with violence and oppression in ordinary settings. Kalita is justly renowned for this. But, to me, even rarer and more difficult is her complex and sad affirmation of life, despite its many tragedies; this comes through most magnificently in the title story. Kalita’s stories also share with Erskine a refreshing ability to step out of genteel middle-class concerns and, with Murugan, an ability to go beyond metropolitan realities.

Ranjit Hoskote’s The Atlas of Lost Beliefs (Arc Publications) is the only new Indian English poetry collection that I read this year. Alas. Hoskote has a reputation as a difficult, intellectual poet, and I avoid overly intellectual poetry. But, in Hoskote’s case, this reputation is misleading, because his sensibility is steeped in a very wide reading of literature and in folk poetry, much of it through translation, and he engages with the world out there, the material world on which any idea can bounce and knock you out cold, the world of poetry. That is why the intellectual effort one needs to put into reading Hoskote is always rewarded.

Like all lists, this is a partial one: I read only about 15 books that were published in 2020, though many more from earlier. There are so many books I could not read, will never manage to read. And some that I definitely intend to read, such as Avni Doshi’s Burnt Sugar and Samit Basu’s Chosen Spirits.

More Columns

The Usual Gangsters Kaveree Bamzai

Kani Kusruti: Locarno Calling Kaveree Bamzai

Return to Radio Kashmir Kaveree Bamzai