String Theory

READING ARCHANA SHAH’S Crafting a Future is like opening the carved rosewood doors of a cupboard full of the fabled textiles of the Indian sub-continent and having them tumble out in a multitude of histories. If you are fortunate, you may be able recall the exact texture and fragrance of the resplendent weaves that graced the likes of Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Rukmini Devi, Mrinalini Sarabhai, Pupul Jayakar, a scholar like Martand Singh, or the exquisite cinematic evocations of a Satyajit Ray. As Laila Tyabji, a craft activist and a living legend herself, tells us in the foreword: “Handlooms are the warp and weft of the subcontinent.”

Just saying the names; tussar, kantha, telia rumal, khadi, jamdani is akin to chanting the thousand names devoted to the celebration of Indian cotton, jute, wool, or the lowly silkworm. It’s now been verified that coiled inside the copper beads, found at a site in Harappa, there were threads of silk. This is a possible indication that silk threads were known to the inhabitants of the Indus Valley. They may have travelled across the Silk Route, or been home-grown for the luxury market.

Archana Shah is a marvellous storyteller, never mind that these tales have been spun at length by others. Early on, as might be expected, Shah checks in at Wardha, the stark setting of Mahatma Gandhi’s early experiments with khadi in Maharashtra. She quotes Gandhi, “If we have the khadi spirit in us, we should surround ourselves with simplicity in every walk of life.” At the same time, Gandhi was also pragmatic enough to underline the need for village industries. Or as she explains, he understood that “unless towns set the fashion in khadi, it becomes most difficult to persuade villagers to spin.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

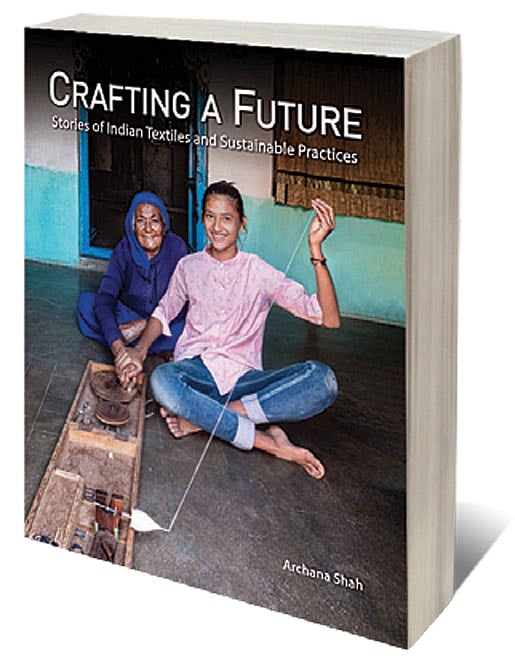

Shah creates an intimate and informed text, having travelled for two years to different nodal points of handloom weaving traditions, furthering her expertise gained over 40 years at Bandhej, a clothing company. Each page has a limpid array of images, portraits of spinners, weavers, artisans, merchants, designers, models and the impedimenta of the trade. Of these, the scenes of the women of all ages sitting together spinning or reeling, or engaged in weaving are the most poignant.

In one of the most charming stories, she describes how Shabnam Ramaswamy was inspired by a woman who had lost her mother, weeping into her mother’s embroidered kantha quilt and saying, “It still holds my mother’s fragrance.” It was the start of a revival of kantha embroidery in the Katna area

of Murshidabad.

Another chapter set in Majuli, the island on the Brahmaputra river in Assam is a reminder of how deeply interwoven these stories can be. Shah talks about Shanti Deva a progressive Vaishnavite saint on the island who encouraged people to perform different art forms regardless of caste and religion. She continues the thread with the life of Sanjoy Ghose, the rural development activist who had started URMUL (Uttari Rajasthan Milk Union), the self-sustaining co-operative near Bikaner working with the weavers in the region, before moving to Majuli. He was tragically kidnapped by ULFA (United Liberation Front of Asom) in 1997. His body was never found. As Shah writes, his vision continues with the work of Jamini Payeng, of the Mishing tribe. Shah tells us how Ghose himself had been inspired by Verghese Kurien’s initiative at Amul in creating a self-sustaining model of a co-operative movement run by people in the field. She also credits the Telecom Revolution in the 1980s pioneered by Sam Pitroda under Rajiv Gandhi for promoting Indian textiles.

Her afterword with its clear-eyed recommendations is an action plan. With a map showing the landscape of Handloom India together with a handy reckoner of its textile wealth, Shah has spun a web of many colours.