Resistance and Resilience

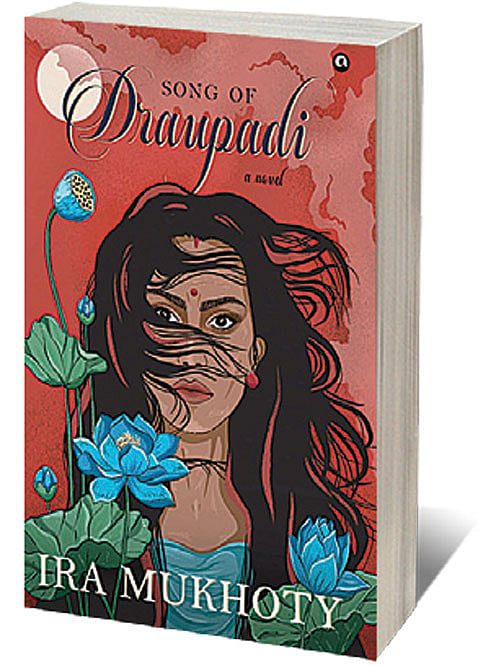

IRA MUKHOTY’S FIRST novel, Song of Draupadi, reads much like her previous books that are located in and around the Mughal courts. Redolent with the smells, tastes, colours and textures of a richly detailed women’s space, this time in the Mahabharata, Mukhoty’s narrative explores the inner rooms and the inner lives of women with whom many of us are already familiar. But even as we enjoy the sensual pleasures of their clothes and their perfumes and their food, we become privy to things less pleasant—to their deeply felt emotions, their complex motivations, their desires and their secrets, the different kinds of darkness they hold within themselves. The wellspring of Mukhoty’s imagination, she tells us in her ‘Author’s Note’, lies primarily in Bibek Debroy’s translation of the complete Mahabharata; it is from here that she imagines conversations and impulses to action, fears and aspirations and the steely exteriors that mask the inner turmoil of the women in the story, all of whom, even in the male-dominated traditional texts, are compelling characters that we might like to know better.

Although Mukhoty’s novel is titled Song of Draupadi (and it is the dark-skinned, fire-born wife of the Pandavas who occupies much of the book), it is, actually, much more a chorus of women’s voices. The book starts and ends with Draupadi, but the Kaurava queens—Satyavati, Gandhari and Kunti, even Ganga—all get a reasonable share of writer’s attention. Mining translations of the Mahabharata for what lies beneath or in between the lines, Mukhoty fills out these women such that we see them pushing back against an indomitable patriarchy with varying degrees of success and failure. Gandhari stands up to the betrayal about her chosen bridegroom by binding her eyes, Draupadi strains against the injustice of being married to five men that she must treat equally, Satyavati refuses to accept that her royal daughters-in-law will not produce heirs for the throne of Hastinapura—each of these women asserts herself, strives for a modicum of agency in a system and a world that sees her mainly as a vehicle of procreation. Among these brave and radical women that Mukhoty has chosen for the story of resistance and resilience that she wants to tell, I miss Amba, the only woman who wilfully and determinedly transcends the constraints of a female birth and returns to exact her cold and bitter revenge.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Apart from studiously avoiding the magical ways in which women are impregnated in the Mahabharata, Mukhoty makes another interesting choice when she reduces the ghastly war, the very heart of the text as we know it, to a few scant pages. I believe that it is in this blind genocide that the Mahabharata redeems itself, as it were. Son after son is sacrificed for a kingdom that no longer means anything to anyone. Brothers, cousins, allies, teachers, elders, students either kill each other or die at one another’s hands. On this battlefield of righteousness, this dharmakshetra, the roots of patriarchy and its pervasive ideologies are shaken. It is here that the Mahabharata’s celebration of heroic masculinity becomes a tragedy for the whole of humankind. If we are going to upend the Mahabharata, to turn its own purported values upon themselves, we must look not only at the way its women live and act but to the war and its aftermath: at mothers mourning their loved and unloved sons, at men who weep for teachers, brothers, sons they have slaughtered without mercy. This is where the patriarchy slays itself.