‘Reliving your life is superior to living it,’ says Gurcharan Das

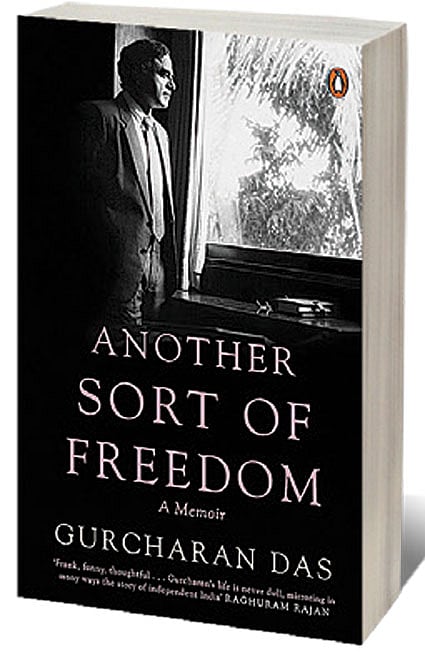

WHEN YOU RELIVE your life, it’s almost better than living it,” Gurcharan Das says. It’s early in the afternoon in Mumbai, and I’ve just asked Das about a moment in his life, when after fleeing their home in Lahore during the Partition, he witnessed two teenagers stab a Muslim officer to death. Das was about four then, and he describes that memory vividly in his latest book Another Sort of Freedom (Allen Lane; 296 pages; `699), of waiting at the Jalandhar railway station, one platform filled with Hindus and Sikhs heading to Delhi, and the other with Muslims waiting for one that could take them to Lahore. The thing with memories is, he says, that while they can seem forgotten, when you look back and focus, they can come back, sometimes in a vividness that is often not possible to comprehend in that living moment. “When you’re living at a moment, there’s just too much going on. You don’t notice the colour of the wall or the type of doorknob in the room. But when you’re remembering, then you do remember [these details],” he says. “I learned this from reading [Marcel] Proust.” He says, “The memory of an event is actually superior to the event itself. In the same way, I think reliving your life is superior to living it. I know it sounds a bit bizarre.”

For decades now, Das has been a familiar face. Looking on from his newspaper columns, interviews on TV and his books, this former corporate honcho turned writer has been analysing India’s growth story and championing market reforms, apart from also looking into ancient Indian history and philosophy, to explore concepts such as dharma or morality and kama or desire. During the pandemic however he began to do something different. He began to look inward, to the story of his own life.

Das’ latest work, a memoir titled Another Sort of Freedom, is the result of that introspection. It begins in Lyallpur (now Faisalabad) in undivided India, where he was born, and his early childhood in Lahore, and charts the fascinating story of his life, as Das and his family escape the bloodshed during Partition to make a new life in India, and how Das, who moves abroad to study philosophy at Harvard University, rises to the very top of a corporate career, only to quit it all to become a full-time writer. The book zips around the globe, from the dusty by-lanes of India where a young Das, then an intern is moving around to conduct market research, to New York, Mexico, Madrid and elsewhere as he rides up the corporate ladder, and moves from corporate boardrooms to halls of academia, balancing between his father’s exhortations of “making a life” and his mother’s of “making a living”. It is a touching and contemplative account of a life, as he suggests in the book, that has been an exercise in living lightly, “not like a feather but like a bird”.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Das was initially not inclined to do a book on his life. His publisher Penguin had been pushing him to write an autobiography for many years. “They said readers and booksellers have been asking them about a story of how this guy who was a business leader became a writer,” he says. “But I used to let it in from one ear and out the other.” This changed during the pandemic.

Another Sort of Freedom is as much a memoir as it is a treatise on Das’ secular idea of moksha or freedom. Three of his previous works—India Unbound (2000), The Difficulty of Being Good (2009) and Kama: The Riddle of Desire (2018)—had dealt with three of the four goals of the ideal life (artha or material wellbeing, dharma or morality and kama or desire) according to the ancient Indian concept of the purusharthas. He had shied away from the fourth, moksha, because Das, who identifies as an agnostic, did not believe in the concept of the afterlife. During the pandemic however, when leafing through a copy of the Monier-Williams Sanskrit–English dictionary, he learnt, he says, that moksha’s original meaning was simply to be free. “Historically, moksha had nothing to do with religion or spirituality. It just meant to be free. If you go to the Monier-Williams Sanskrit–English dictionary, it gives many examples of moksha, from a person who repays a debt, a prisoner released from jail, to a horse without a harness,” he says. Das, who had always felt his life was an attempt to free himself from the expectations of others, could identify with this secular notion of moksha. Through the concept of moksha he found the lens through which he could attempt a memoir. “Every book of mine is partly in the first person. And as I started thinking about moksha, I thought, well, this may be a good way to think about my own life and I started connecting the dots,” he says.

Das’ mother had studied atKinnaird College, in Lahore, where a nun had instilled in her the habit of keeping a diary. She had returned to her diary to answer Das’ queries about life in Lyallpur before the Partition, when he was writing his first novel (A Fine Family, 1990), which followed the story of a family uprooted during the Partition. And before she died, she had handed him this diary, along with letters he had written when he was studying in the US. These would prove invaluable when Das began writing this memoir.

Das had also maintained a journal since his youth. He used to write letters every Friday to his family when he was studying at Harvard University. But when he sent his mother a letter once, discussing the existentialists who he was reading then and Albert Camus’ line that suicide was the only true philosophical problem, his father wrote back saying never to write such a letter to his mother anymore. “So instead of writing letters, I started keeping a diary and that’s how the diary began. It [writing] was also a useful way to order my thoughts and to clarify my own thinking,” he says. But when he returned to them when he began this book, he found them tedious. “I had so much material,” he says. “To tell you the truth, I used to get bored reading my own diaries and I would tend to skip over.”

Das’ biggest concern when writing a book about himself was to not give into the temptation of flattering himself. “The human temptation is to want to look good,” he says. “You know the books about business people and ‘how-great-I-was’ kind of stories. They’re very boring and pompous. And that’s just not the kind of book I wanted to write. And so, one had to be honest, and I had to bring out the problems in one’s life, especially the mistakes I made, and the bizarre things, which I never understood myself.”

The book also contains some fascinating accounts of managing a business during the socialist era of the 1970s and 1980s, like the time when Richardson Hindustan Ltd in India (before its acquisition by Procter & Gamble), where Das was serving as CEO, was in a slump, and how he and his team decided to rebranding Vicks as an Ayurvedic product, thereby exempting themselves from price controls, excise duty, and licence requirements, and turning around the company’s fortunes. On another occasion, when a flu epidemic in the country led them to produce more Vicks cough and cold products, Das was summoned by a bureaucrat in Delhi for exceeding the permitted production limit. “What a stupid and bizarre thing this license raj was,” he says. “Here we were thinking we were producing for the country, that we were keeping the shelves of pharmacies stocked during an epidemic. And here was this bureaucrat talking about a jail sentence. I don’t know what got into me and I told him, ‘Look, what if this news appears in the papers? How do you think our country will look in the eyes of the world, how would our prime minister look, that during an epidemic, the reward for helping producing products that alleviated peoples’ misery, was to send the executive of that company to jail?’”

Das identified as a socialist early in life, but he had become disenchanted with socialism, and he even joined Swatantra Party, the now defunct liberal party that championed the free market.

For long, Das dabbled in both the corporate and literary worlds, working through the week in his regular job, and writing plays and books during the weekends. Both these worlds, he says, tended to view him as an oddball and considered him unserious for engaging with commerce and the arts. But he was growing discontented. “I often used to ask myself, ‘Is this what life is all about?’” he says.

The mask fell off in the 1990s, when there appeared to be a backlash within the Congress Party against the 1991 economic reforms. Das was then in the US, at Procter & Gamble’s headquarters in Cincinnati, where he was heading the company’s worldwide strategic planning for the health and beauty business. “I was listening to NPR [National Public Radio] about the reforms being in trouble. For me, 1991 was truly the time when we got our true freedom, our economic freedom. In 1947, we had gotten only our political freedom... So the reforms were very important to me. The left wing of the Congress party was asserting itself and the Leftists were much more articulate and there were no real defenders of the reforms... Margaret Thatcher used to say that she spent 20 per cent of her time doing the reforms and 80 per cent selling them. Well, nobody was selling them in India, and I was worried that the reforms might get reversed,” Das says. He returned to India, with the thought of defending the reforms through his writings.

To Das, India remains an unfulfilled potential. One of his popular phrases, used earlier, was that India grew at night, when the government slept. “We still continue reforming by stealth,” he says, and points to the difficulties the Modi government has experienced in selling reforms like the farm laws, the labour codes and the land acquisition bill. “They do not get passed because nobody has really bothered to sell the [free] market to the people in our country,” he says.

It’s been over 30 years since the economy was liberalised in 1991. Where does he think the country’s economy stands today? “We have grown at almost 7 per cent, and we have lifted about 400 million people above the poverty line. It’s quite an achievement. Our model however has been wrong,” he says, pointing to how the country has failed to create labour-intensive manufacturing growth. “We’ve jumped from creating a green revolution to an IT revolution, but we have skipped the major step of an industrial revolution. We have failed in this respect. How else will we take the people working on farms to higher productivity jobs?” he says.

But Das as always remains hopeful. “We are in a great position today to do this [reforms],” he says. “If I was a betting guy, whoever wins in 2024, I would bet that we would make those reforms.”