Books | Best of 2020 Books

Pratap Bhanu Mehta

Political scientist and columnist

Open

18 Dec, 2020

Open

18 Dec, 2020

IT IS difficult to pick new books in a year where there is an embarrassment of riches; one is also hampered by the fact that some of the best ones are written by close friends and colleagues that mentioning them felt like self-promotion and had to be left off. So the list below should be read with the caveat that many other books easily deserved to be on this list.

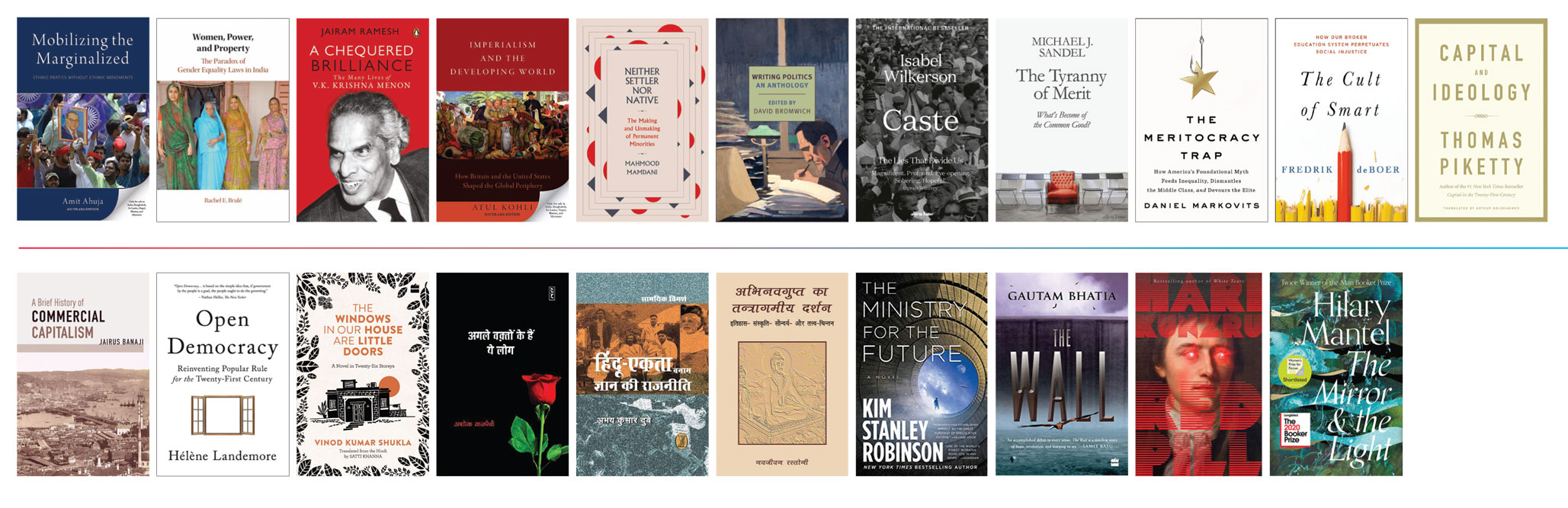

Professional matters first. Amit Ahuja’s Mobilizing the Marginalized (Oxford University Press) is a brilliant study of the interface between Dalit social and political movements. Rachel Brulé’s Women, Power and Property: The Paradox of Gender Equality Laws in India (Cambridge University Press), is a marvel of data collection, history and insight into the relationship between gender and the state. Jairam Ramesh’s biography of VK Krishna Menon, A Chequered Brilliance (Viking), is stunning in the sources it collects, and in letting the sources speak for themselves. It still leaves Jawaharlal Nehru’s undue regard for the man a bit of mystery. Atul Kohli, Imperialism and the Developing World: How Britain and the United States Shaped the Global Periphery (Oxford University Press) is the magnum opus of an amazing scholar, but also vital to understanding the modern world. It is well read in conjunction with Mahmood Mamdani’s Neither Settler Nor Native (Harvard University Press) and is a sharp argument on the pathologies of the Nation State Form.

I happened to chance upon a new anthology by David Bromwich, Writing Politics (NYRB Books), a collection of some of the greatest political writing ever. But a short essay in it, written by one of the greatest 19th-century minds, George Eliot, on anti-Semitism, ‘The Modern Hep!Hep!Hep!’ cuts through the cant of any nationalism displaying prejudice. On that theme, Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste (Allen Lane) takes on the subject of caste and race. Indian critics are quibbling over the details, but its anatomy of human oppression is powerful and crystal clear.

The theoretical attack on meritocracy to which I fully subscribe seems to be the big theme of the year, captured in three books. Michael J Sandel, The Tyranny of Merit (Allen Lane), is a work of great elegance and insight; Daniel Markovits, The Meritocracy Trap (Penguin), is comprehensive and compelling; and a lesser known book by Fredrik deBoer, The Cult of Smart (All Points Press), is impassioned and radical on the subject. On a larger canvas of capitalism, Thomas Piketty, Capital and Ideology (Harvard University Press), is a tour de force worth the thousand pages. Jairus Banaji, A Brief History of Commercial Capitalism (Haymarket Books), is a brief but stunningly erudite contribution to the history of capitalism, and relevant to debates over the relationship between merchants and producers in capitalism. For a big idea for the reinvigoration of democracy, Hélène Landemore, Open Democracy (Princeton University Press) is a great defence of both sortition and deliberation as complements to representative democracy.

The theoretical attack on meritocracy to which I subscribe seems to be the big theme of the year, captured in three books. Michael J Sandel, The Tyranny of Merit is a work of great elegance and insight; Daniel Markovits, The Meritocracy Trap is compelling; and Fredrik Deboer’s The Cult of Smart is impassioned and radical

Share this on

Vinod Kumar Shukla, Deewar Mein Ek Khidki Rehti Thi (Vani Prakashan) is a beguiling and beautiful novella, now published in a translation by Satti Khanna (The Windows in Our House Are Little Doors). Ashok Vajpeyi’s Agle Waqton Ke Hain Ye Log (Setu Prakashan), turned out to be a light but lovely personal history of the key figures of Hindi letters and music; Apoorvanand’s forthcoming book on Premchand, already serialised on Satyahindi.com, is a sensitive, poignant take on the writer and our times. Abhay Kumar Dubey, Hindu Ekta Banam Gyan Ki Rajneeti (CSDS), gets the longer term trajectory of Hindu nationalism in ways that most English commentators miss. Navjivan Rastogi’s collected philosophical essays, mostly on Abhinavagupta and the history of tantrism, Abhinavagupta Ka Tantragamiya Darshana (DK Printworld), is an unusually interesting contribution to Indian intellectual history.

These days if you want serious social theory, you should turn to fiction. There is no clearer and more entertaining guide to the combination of financial capitalism, environmental catastrophe, and technological optimism than Kim Stanley Robinson. His The Ministry for the Future (Orbit) is a nice companion to his New York 2140; Gautam Bhatia’s The Wall (HarperCollins) is a significant Indian debut in science fiction on the theme of freedom. Hari Kunzru’s Red Pill (Scribner) seems to capture the paranoia of our time, over both privacy and right-wing conspiracy theories, quite well. Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror & the Light (Fourth Estate), the final volume of the Cromwell trilogy, is truly great literature that leaves you wanting more.

More Columns

Author Thomas Suárez presents peace framework for the Palestine-Israel crisis Ullekh NP

Shubhanshu Shukla Returns to Earth Open

Nimisha Priya’s Fate Hangs In Balance, As Govt Admits It Can’t Do Much Open