Planet of the Potentates

A compelling treatise by a seer-savant studies what the ascendancy of Homo sapiens has made of our world

The clairvoyant (certified captain crankypants) Maharashtrian surgeon PV Vartak, who claims to have undertaken his first experiment of astral travel in Samadhi to the planet Mars on 10 August 1975, spent his post-retirement years consummating two major projects: the first a treatise to prove Christ was actually a Hindu Tamil Brahmin, the second an astronomical dating of Valmiki's Ramayana. According to Vartak the various tithis in the text establish a particular arrangement of celestial bodies, occurring singularly once in many thousands of years, to prove 4 December 7323 BCE as Rama's date of birth. The Ramayana occurred over 9,300 years ago; unfortunately, for Vartak, this does open violence to Hindu theology and plays directly into the hands of Romila Thapar and her description of the Ramayana as a sort of exaltation 'of the local conflicts between the agriculturists of the Ganges Valley and the more primitive hunting and food-gathering societies of the Vindhyan region'. A Neolithic, inter-tribal abduction. Well, happy Dusshera to you as well.

It could have been worse. A Neolithic inter-species abduction, if things had gone differently for the New Stone Age: 'Until about 10,000 years ago, the world was home, at one and the same time to several human species. And why not? Today there are many species of foxes, bears and pigs. The earth a hundred millennia ago was walked by at least six different species of man. It's our current exclusivity, not that multi- species past, that is peculiar – and perhaps incriminating.'

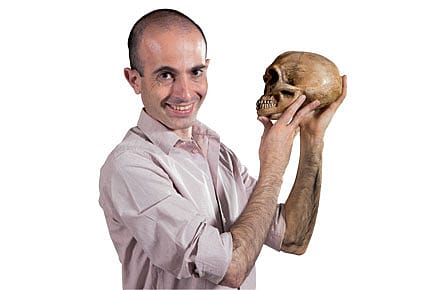

Yuval Noah Harari's wonderful new book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, in direct antagonism to all that we hold dear, raises this right at the beginning and lets it hang in our minds like a grim family secret. But first, what is a species? Animals are said to belong to the same species if they can copulate with each other to produce fertile offspring. It has nothing to do with the commonalities of features and physical attributes. A bulldog and a spaniel may look quite different, but they're from the same species and therefore perfectly capable of boinking each other (willingness is another matter). The fruit of their loins will have what it takes to carry their genealogical line forward. A horse and a donkey, on the other hand, despite much of a muchness physically, might be induced to boink, but their offspring, the mule, will be sterile. The first chapter of Harari's retelling of the story of mankind sizzles with the testicularity of just one species of humans: ours. Homo sapiens. There were at least six others that lapsed under the firmament. What happened to them? If Harari is to be believed, what transpired steadily but surely over the Mesolithic period was the first and most significant ethnic cleansing campaign in history. (If Vartak's calculations are erroneous, and Treta Yug happened earlier, might the exertions reported and romanticised in Yuddha Kaand have had something to do with such a campaign?)

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The first chapter ends with the most audacious what if: 'Imagine how things might have turned out had the Neanderthals or Denisovans (or the other human species) survived alongside Homo sapiens. What kind of cultures, societies, political structures would have emerged in a world where several different human species co-existed? Would the book of Genesis have declared that Neanderthals descended from Adam and Eve? Would Jesus have died for the sins of the Denisovans, and would the Qur'an have reserved seats in heaven for all righteous humans, whatever their species? Would Neanderthals have been able to serve in the Roman legions or in the sprawling bureaucracy of imperial China? Would the American Declaration of Independence hold as a self-evident truth that all members of the genus Homo are created equal? Would Karl Marx have urged workers of all species to unite?'

Harari, a historian at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's department of Humanities, is a first rate sherpa for a story like the magic mountain. A story about the ability of sapiens to create fictions and believe in them collectively, like Gods and Demons and Nations and Money and Limited Liability companies and Human Rights, all figments of our high-yielding imaginations. We're the story-telling mammal. More correctly, story-believing is the physiology of our species: 'You could never convince a monkey to give you a banana by promising him limitless bananas after death in monkey heaven.'

And a story that starts off with the socio- political world of the foragers and the first wave of colonisation of Australia and America (between approximately 12,000 and 9,000 BCE), one of the biggest and swiftest ecological disasters to befall the animal kingdom. Homo sapiens drove to extinction half of the planet's big beasts (ie elephant birds and giant lemurs) long before they invented the wheel, writing or iron tools. From the continuities they were able to set in motion, we are given the first revolution—around 9,500 to 8,500 BCE—in the hill country of south-eastern Turkey, western Iran and the Levant: the manipulation of the lives of a few animals and plant species. History's biggest fraud—the agricultural revolution. Fraud because the average farmers worked harder than the average foragers and got a worse diet in return. It was an insignificant grass that ended up manipulating us to its advantage, making us break our backs clearing fields and lugging water from streams, nursing it with animal faeces and making us settle permanently next to it: wheat. Even today, more than 90 per cent of our calories come from the handful of plants our ancestors domesticated between 9,500 and 3,500 BCE— wheat, rice, maize, potatoes and barley. No noteworthy plant or animal has been domesticated in the last 2,000 years.

In Harari's proportionate view of history, an astonishing number of pages are spent on imagined orders, ie, how myths can sustain communities, nations and empires. He does rather more than a voiceover here. One might legitimately surmise this is a manifesto. Sample this bravura passage where he (as biologist-knight errant) translates the most famous line of the American Declaration of Independence, saying:

'According to the science of biology, people were not 'created'. They have evolved. Evolution is based on difference, not on equality. Every person carries a somewhat different genetic code, and is exposed from birth to different environmental influences. This leads to different qualities that carry with them different chances of survival. Equally, there are no such things as rights in biology. There are organs, abilities and characteristics. Birds fly not because they have a right to fly, but because they have wings. And it's not true that these organs, abilities and characteristics are 'unalienable'. Many of them undergo constant mutations, and may well be completely lost over time. The ostrich is a bird that lost its ability to fly. There is no such thing as liberty as well in biology. Just like equality, rights and limited liability companies, liberty is something that people invented and that exists only in their imagination.

We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men evolved differently, that they are born with certain mutable characteristics, and that among these are life and pursuit of pleasure.'

There will be plenty of eye-rolling and head-shaking over such a tract, particularly by liberal humanists. So that's the reason we aggrandise the American Declaration of Independence? Would such a defence be valid for the execrable bylaws of Manusmriti? Or Hammurabi's code? The sort of argument Harari exults in.

This is a book that carries within it multiple, smaller meta treatises: how contradictions created culture; why polytheists, even when they conquered huge empires, never proselytised; how Buddhism is so uncannily proximate to Marxist dialectics; how liberalism and communism undermine Darwinian natural selection; why in the early socio- political systems of China, India and the Muslim world merchants and mercantile thinking was despised; how middle class Europeans in the eighteenth century looking for a good investment created the slave trade to America.

Harari's impossible scheme of hoisting these polemics on the history of money, religion, empire and capitalism is what makes it such a fine work of potted ontology in 400 pages. Sapiens is the work of a seer and a savant who has written it lying face down in the kitchen midden. As we come to the end, we are all clear-eyed about the speciation of the modern Homo sapiens, the biological prime mover. The long view is that everything in the affairs of the human animal is connected. To each other and to the midden. Deepika's cleavage, Modi's MSG speech, labour law reforms, Twitter nationalism, the ISIS, Ebola: all exegeses on the human condition are found in that dogged connectedness.

(Ambarish Satwik is a vascular surgeon and the author of Perineum: Nether Parts of the Empire)