People’s Minister

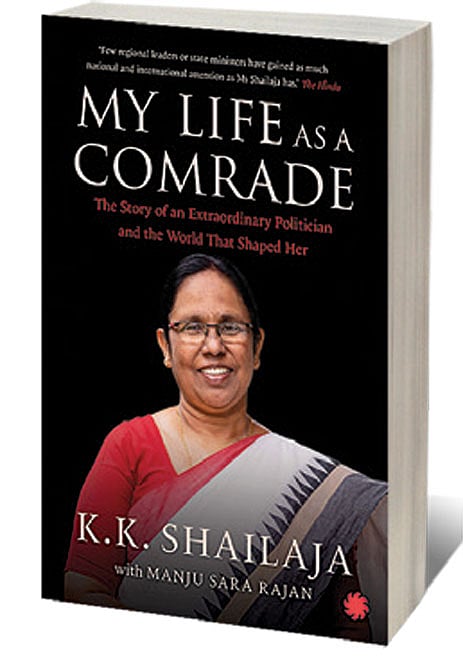

THIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF Kerala’s former health minister KK Shailaja is, in fact, the real “Kerala story”. You would not guess that from the title of the book. Yet, half of this disarmingly straight-forward account of one life is more about why the state of Kerala stands out as so different from the rest of India than about the author.

Teacher Shailaja, as she is popularly known, became a familiar name not just in India but around the world during the recent Covid pandemic because of the way the health ministry she headed handled the crisis. She was profiled in international media and received recognition and awards. But as she emphasised then, and does so again, the success could not be credited to just one individual.

The author explains the many policies that preceded the Covid pandemic which prepared the state to handle it better than most others. For instance, all Indian states have primary health centres (PHC). These and their sub-centres are supposed to be the first port of call for any individual seeking healthcare, particularly in rural areas. When Shailaja took over the health ministry, she checked the status of PHCs. Many needed upgrading with equipment and personnel. Renaming them Family Health Centres, her ministry went ahead and did this despite budget constraints by roping in the local community. Similarly, facilities at the tertiary level also needed improvement. By taking these measures, Kerala was better prepared when struck by a health emergency.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

In 2016, when Shailaja initiated these steps, no one knew that within a few years the state would be faced with its biggest health emergency. Before the Covid pandemic, the state had to deal with the fallout of a cyclone, floods and then the Nipah virus. In many ways, the strategies developed to deal with each of these crises were invaluable when the state faced the pandemic.

Shailaja believes that most people in Kerala accept that the state should provide basic services for people such as education and health and that a participative grassroots-base is essential when faced with a disaster.

The book, however, is not just about health management. In the first part, the author describes the Malabar region where she grew up, which differs physically and culturally from coastal Kerala. She backgrounds her own involvement in public life by telling us about her family members, like her great grandfather, who was respected for his work for the community. People in the region, she writes, embraced communism because of the “rebellious and egalitarian sensibility” that prevailed there and she believes she was “anointed even before I was born” with that philosophy.

Shailaja emphasises that although her family members were involved in politics and public life, they were not politicians. This differentiation is interesting. It stems from her belief that as a communist, you can fight for social justice without necessarily becoming a politician.

Yet Shailaja did become a politician. Not only did she join the Communist Party of India (Marxist) but she also stood for Assembly elections and won. And in 2016, she was appointed a minister.

Although her account of the challenges she faced as a politician and a minister is fascinating, Shailaja is remarkably honest about her limitations. She admits that despite her family background, it was not easy for her to become a politician, and at the same time fulfil what society demanded of her as a woman and a mother.

“A professional life is positioned as a luxury in a woman’s life, as though it is a perk or an allowance offered by the kindness of those around us,” she writes. And when women believe they have something to offer society, they are “conditioned to feel guilty for it.” That guilt, she says, has stayed with her. A reflection perhaps on the status of women in India’s most progressive state.