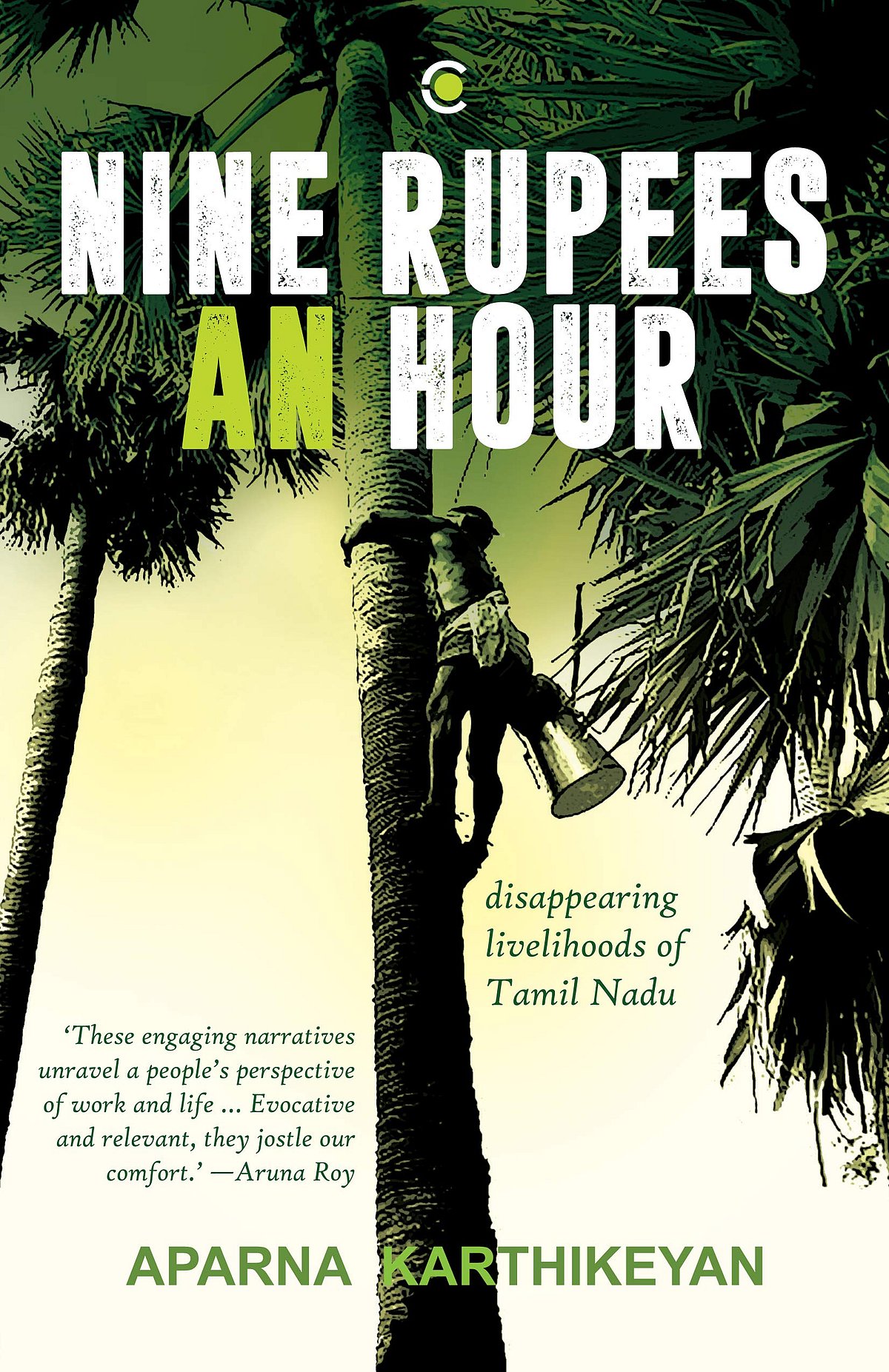

Palm tree Tappers to Sickle Makers

A world driven by ‘big’ ideas—growth, development, globalisation, nationalism—unavoidably creates a trail of human and material debris in its wake. Whereas the big ideas are championed and held aloft by state and corporate interests, counter-narratives—on the lives destroyed by such dominant forces—have been few and far between. In recent years, however, we’ve heard and read powerful first-person accounts from, among others, victims of a nuclear accident, survivors of the horrors of Partition, and minority women whose lives were rent asunder by communal riots. Nine Rupees an Hour by Aparna Karthikeyan, an exploration of vanishing livelihoods in Tamil Nadu, is the latest addition to this emerging branch of narrative journalism.

In the book, the author covers ten occupations in rural and semi-urban Tamil Nadu that would most likely become unviable in the near future. Four are related to farming and the remaining are artisanal or involve the practice of performing arts in the folk tradition. Each occupation is marked by a wealth of traditional knowledge and skills, arduous toil and uniformly bleak economic prospects. The stories of these declining livelihoods are essentially crafted as narratives centred on an individual, family or group in a particular setting, and on their current struggles in the pursuit of a vocation that, for a host of reasons, may not survive into the next generation.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

In each story, the author brings us the historical background of the vocation that throws some light on its current predicament. In a story on palm tree tapping, we learn about the origins of the palm tree as well as the practice of the occupation during the colonial period. The caste-based nature of most occupations listed in the book and the stigma attached to palm tree tapping because of the association with toddy are also highlighted. Sickle-making in the present is placed in a historical continuum of iron implements made and used in the Sangam period and references to the sickle in Periyapuranam, a work of Bhakti literature from the 12th century. A discussion of Bharatanatyam leads to sadir, a dance form practised by the devadasis for centuries and appropriated in the early 20th century by the Brahmins. Handloom weaving in Kancheepuram, a major centre of learning by the 7th century, goes back more than a thousand years. The sense of loss evoked by references in the book to the history of these traditions is immeasurable.

The author is equally attentive to the process and materials involved in each occupation. For example, her description of how the different parts of a nadaswaram are made is both elaborate and precise at the same time: the main cylindrical pipe from seasoned Indian blackwood and the flared bell at the end from rain tree timber, both turned on a lathe, and the mouthpiece, which is made by hand from reeds. Similarly vivid descriptions are provided for every trade, drawing the reader deep into each story and building respect for the occupation without being patronising.

The economic viability of each trade is examined not just from a financial perspective, the nitty-gritty of costs and prices, but also in terms of branding and distribution, institutional support for financing and promotion, availability of infrastructure and training, and, where relevant, patronage from the communities and ancillary employment opportunities—like teaching for dancers.

Social conditions constitute an important factor in determining the viability of these livelihoods. A formally trained Bharatanatyam dancer from a subaltern community is bound to face discrimination in a domain that’s maintained as an exclusive preserve of Brahmins. A woman who cultivates flowers for selling in a nearby city will find harvesting them alone in the middle of the night and carrying the load to the local collection point impossibly difficult solely because of her gender. Female performers of folk dances will have to overcome discouragement from family and community to pursue their art and an attendant lifestyle. Caste and gender are issues that recur throughout the book.

What makes the book remarkable is the author’s extraordinary talent for telling stories that engage and enrich from beginning to end. She handles each embattled individual with deep empathy, letting them speak in their own voices without intruding on them. The language she uses for describing terrains, locales, methods or people is always vivid and precise. She is also insightful about the web of causality that binds an individual or community to their circumstance and leads them to an inexorable fate.

Brief interviews with a few experts on key factors affecting the trades—public policy, groundwater, banking finance and certification—are a useful supplement to the reportage. However, the ideological exposition and critique offered in interviews with P Sainath and TM Krishina, though well-intentioned, could have been more rigorous and representative. For instance, the dual-economy theory of development, centred on the transition between agriculture and industry, went out of fashion 40 years ago. We are now in the neoliberal era that wilfully pays scant attention to issues of employment and social welfare. Similarly, even at the level of discourse, we need to go beyond Krishna’s pet theories on ‘reshaping art’, and hear directly from subaltern communities on their conception of art and its expression in relation to their lives. The book would have been served better by well-researched, coherently argued essays by the author in the place of these interviews.

Nine Rupees an Hour may not succeed in reversing the pitiless course of history, and ‘make whole what has been smashed’. However, as a counter-narrative of our times, it can add to our collective memory and shape public conscience in the times to come. And that possibility is a testimony to its value and triumph.