Palace Intrigue

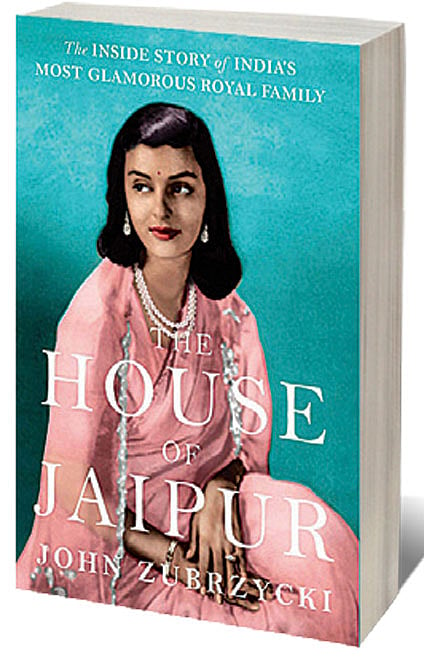

WHEN THE UMPTEENTH book on Indian royalty, particularly on the House of Jaipur (Kachhwaha would be more correct if less elegant) is published, the question to ask is ‘Why another one?’ Well, if the eponymous book promises ‘The Inside Story of India’s Most Glamorous Royal Family’, a grand romp through the palaces, forts and shikaar lodges of Rajputana is the least readers expect. As John Zubrzycki is no Jilly Cooper, the book provides a bird’s eye view of the march of Rajputana from feudalism to India’s independence even as it chronicles the life of the person who actually brought ‘glamour’ into that royal family and is the fulcrum of the story: Gayatri Devi or Ayesha, the beautiful princess of Cooch Behar who married the dashing Maharaja Sawai Sir Man Singh II.

Before the champagne and shikaar-laden romance of ‘Jai and Ayesha’ became the stuff of international headlines and elevated Jaipur to a plane beyond their 17-gun-salute status, it was not very different from the other princely states that settled down to life under the British Raj much as they had under the Mughals. Gayatri Devi arrived in Jaipur as ‘Third Her Highness’ in 1939 and proceeded to impact royal Rajput life within and without.

Jaipur had been on the right side of the rulers in Delhi ever since the Mughal era. The fabled Kachhwaha wealth can be traced to the original Raja Man Singh who, as Akbar’s most trusted general, had brought back camels laden with loot from campaigns. British rule also saw Jaipur hobnobbing with the powerful, as the book recounts, but independence presented a quandary. That is when its maverick Maharani deviated from that Jaipur policy, joined C Rajagopalachari’s Swatantra Party and triumphantly entered the Lok Sabha with a record-breaking victory margin, thereby showing India’s defenestrated rulers a way to regain (or retain) relevance in a new India.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

However, from Gayatri Devi’s stepson ‘Bubbles’ Bhawani Singh’s disastrous foray into politics as a Congress candidate during Rajiv Gandhi’s years to his daughter Diya Kumari’s victories on a BJP ticket, the return of the old Jaipur policy is also manifest. But Zubrzycki’s prediction that she is chief ministerial material may be premature, as also his assessment of her polo-playing fashion model son Padmanabh, the current ‘maharaja’ whose adoption by his grandfather and subsequent ‘coronation’ divided Rajput society. Yet Gayatri Devi’s legacy endures. Even what played out in Rajasthan recently with rebel Congress MLAs being whisked away to prevent ‘poaching’ can be traced to a precedent set by her: in 1967 she had corralled the opposition first at the City Palace in Jaipur and then at Kanota Fort in an unsuccessful effort to prevent the Congress from luring them.

Though the Maharani—later Rajmata—was frank about her feud with Indira Gandhi and even recounted having caviar in her grotty Tihar Jail cell during Emergency in her memoir A Princess Remembers, she had been frustratingly laconic about the premature deaths of her husband and son as well as her contradictory actions in the protracted legal battles with her family. Through meticulous research and interviews of friends and fellow royals, Zubrzycki fills in that gap in his book—though the paucity of photographs is a major disappointment. He could have also devoted more attention to her co-maharanis: Marudhar Kanwar and Kishore Kanwar, the latter reputedly as beautiful as Gayatri Devi and with a magnetic personality too.

To answer the question ‘Why another one?’ Well, because it engagingly elucidates how after the sudden death of Man Singh II at a polo match in England in 1970, for the late Gayatri Devi and her progeny, it has been a not-so-glamorous progression from champagne cases to court cases.