“One of my greatest talents is as an eavesdropper,” says Twinkle Khanna

TWINKLE KHANNA NEVER wanted to be an actor. She was destined to be a writer. Books were always her anchor and succour. Family legend says that she was reading by age three. Sundays were her happy time, when she could spend the entire day with oil on her hair, and mangoes and comics by her side. She remembers reading Lady Bird books and Panchatantra. Her love for horror probably arose from the maalish lady who would regale her with stories about ghosts in her neighbourhood. In her teens, she moved towards Arthur C Clarke, and Isaac Asimov her “love,” whose work she has read nearly in its entirety. She was always the salty one who, though shy by disposition, would be willing to stand on a soap box and crack jokes that would offend everyone. She says, “What the writing has done for me is that all my offensive jokes I now have time to edit them and make sure that they’re not that offensive,” she adds, tongue firmly in cheek, “Let’s say, I’ve always been on the left side of, you know, the right people.”

She has been writing for 11 years, but it is only during the pandemic that she started to think of herself as a writer. When the pandemic brought the world to a halt, she realised that she was a “squirrel” gathering material, whether it was an anecdote, dialogue or story to build upon later. “One of my greatest talents is as an eavesdropper,” she says. The lockdowned world showed her for the first time, “I am a writer because I was unable to process the world around me and the things that were happening unless I was writing about them.”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Her favourite writer Asimov once said, “Writing, to me, is simply thinking through my fingers.” Similarly, readers know Khanna’s thinking through her columns. She shares her opinions and observations on everything, from Deepika Padukone’s confessions on Koffee with Karan (she rightly doesn’t see what the fuss is all about) to avocado emojis (she learnt rather late that the fruit on her phone cover was prurient and not just tropical) to Frida Kahlo (the Mexican artist is “fierce and fabulous”). And readers are grateful for it. Channelling her inner quirk and side-eye at the world, Khanna, aka Mrs Funnybones has entertained (and provoked) readers for more than a decade. Luminaries with famous (and not-so-famous) lineages opine as soon as they are propped onto a stage, but Khanna’s USP is that she brings a levity and authenticity to it all. As Mrs Funnybones, she is not trying to prove how much she knows, instead she’s telling us that adult friendships are hard (we agree), that we should occasionally embrace boredom (sure thing) and why “suffering” for beauty may not always be necessary (amen). In the dreary pages of a newspaper, her columns can feel like lemonade on a hot day, a gulp of light and zest to ease our fatigue.

But Khanna is not one to rest on her laurels. And she has many. Today, she is one of India’s highest selling women authors. Chiki Sarkar, her publisher at Juggernaut, highlights her accomplishment, “Very few writers in India sell 100,000 copies of their books in the first year consistently, some may have one book that sells that amount, but their next books settle to a lower number. All of Twinkle’s three books have sold 100k copies in their first year.”

Through her writing, Khanna has found a popularity that escaped her in cinema. Her mother (actor Dimple Kapadia) pushed her into the movies even though she had little interest in them. Today her mother consoles her that if she’d stuck on in cinema, she would be nearing her “expiry date,” and not a bestselling author with years of writing ahead. Khanna adds, “If people had liked my work in the movies, then I would be a millionaire right now! So I wish that they had given that same love at that point of time, but perhaps it worked out for me because maybe if I had all that adulation and love in the beginning, what would I be doing today?”

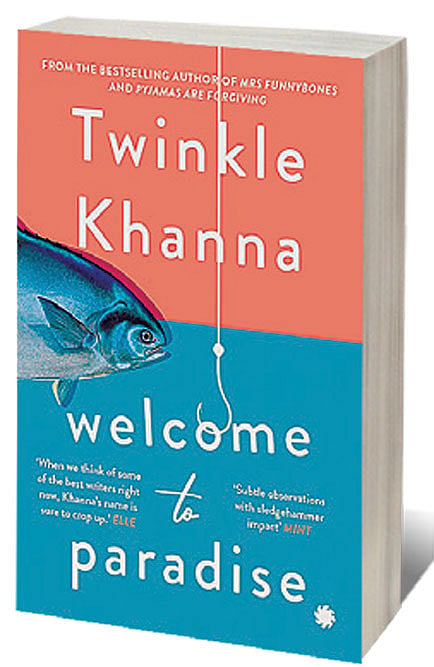

Most ‘literary’ authors can only dream of the love and sales that readers have bestowed on Khanna. The actor-turned-author (who is also an entrepreneur, producer and interior designer) will turn 50 this year, has not quite donned a new avatar, but she has embraced a new voice. Her book, Pyjamas are Forgiving (2018), set in an Ayurvedic spa in Kerala, stayed true to Mrs Funnybones’ inclinations, and was packed with insights and one-liners. Her short story collection The Legend of Lakshmi Prasad (2021) told of characters, such as a young girl who transformed a village located between the Kosi and Ganga, and a septuagenarian who falls for a married man. Her latest collection of short stories Welcome to Paradise (Juggernaut; 224 pages; ₹399) sounds more like Mrs T Khanna and less like Mrs Funnybones. Move over standup star, and take a bow valedictorian. The lemonade has matured into champagne. Welcome to Paradise is also her first book after the completion of her Master of Arts from Goldsmiths at University of London. Adding to her laurels, at Goldsmiths, she received an “exceptional distinction” for her final dissertation.

The five stories in Welcome to Paradise largely deal with themes of loneliness and aging, illness and death, and preparing a face to meet the faces that you meet. While this might sound deathly serious, the book itself is not, as it carries Khanna’s signature lightness, and only proves how big topics make up the business of living. Khanna’s stories are character driven, so they always feel like an embrace and never a dirge.

In ‘Nearly Departed’, 86-year-old Madhura Desai is pleading with the State for the right to die. ‘The Man from the Garage’ tells of family dynamics that unspool around the death of Amma and a discussion over whether her body should be buried or burnt, as she was born into an Ismaili Muslim family, and her husband would visit both temple and jamaathkhana. Khanna uses the debate over ‘burn’ or ‘bury’ as the ignition for the story, which explores substance abuse, addiction, men who succumb and women who stand strong.

‘Jelly Sweets’ is the strongest story in this hard-hitting collection, and, perhaps, the one closest to Khanna’s own life, as it is based on stories that Khanna’s grandmother told her about her childhood in Satpati, Maharashtra. ‘Jelly Sweets’ tells readers about Nusrat who “had lost everything—her husband, her son, and her voice,” but it ends with light filtering in.

On social media, Khanna shares a few of the links between her stories and her life with her 7.5 million followers. She posts pictures of her as a child listening to a story being read by her Naani, to whom the book is dedicated. She writes of her days at a boarding school at Panchgani, which figures in ‘Nearly Departed’. But Welcome to Paradise is make believe. As she says, “It’s all fiction only because the truth is always more palatable when it’s gift wrapped as fiction.” The facts are only for her to know, and she will take them with her to the grave.

WHEN I MEET KHANNA in her office in Mumbai’s Juhu, I ask if she feels typecast into the mould of a funny writer, and if Welcome to Paradise is a break from that. She says, with a laugh, “Now that I’m turning 50, I have refused to fall into these categories. In the book, there is humour. There is lightness, but it is what is required in the story and from the characters. I’ve been under a lot of pressure—I’ve put a lot of pressure on myself, I’m not blaming anyone else—to give people an experience, which is deep yet entertaining. But I am not going to put myself under the pressure of having a funny line in every third paragraph. I’m going to do what serves the story. Luckily, I do write characters which have a strange, skewed perspective. So humour does come in. I can’t live without that. I would get bored!” Welcome to Paradise is written with acuity and precision. Nothing is unwarranted, and every detail (even if it is a certain burning train) serves a purpose in the story.

When Khanna talks about her craft of writing she is unusually apologetic. When she pores over folders on her computer to show me the numerous documents behind each character and the multiple drafts for each story, she keeps saying, ‘Oh, I must be boring you’. Bursting into laughter she says how she is now cautious when she uses words like “temporal continuum” because she hears her late mother-in-law’s voice chastising her that such “big, big words” will scare people at parties. She adds, “Now I don’t use these big words. Because I do want people to sit next to me at parties! Otherwise, how will I have any stories?”

Whether it is the oddball at parties or the daughter who could not match up to her mother’s histrionics, Khanna has always felt like an outsider. She might have uprooted her life in Mumbai to go study in London, in her late 40s, but displacement is her norm. That is why she is perfectly suited to the writing life. She says, “I believe that if you really fit into the world perfectly, then you have no reason to write about it. If you are perfectly happy in the world the way it is, why would you sit alone at your desk and build these entire fantasy worlds inside your head? It’s because you are not completely in sync with everything that’s happening.”

Khanna, who enjoys working with her hands, whether it is crochet or knitting (which she learned from her grandmother) feels most at home when she is surrounded by family and her plants. An avid gardener (her nails are filed down) she has been busy tending to the Ceylon spinach, with its edible leaves and purple flowers. Like her character Madhura in ‘Nearly Departed’, Khanna also has a separate toothbrush to scrub her nails clean. And like Madhura she too has accidentally grabbed it at night only to taste “gritty soil mixed with minty toothpaste”. She lets slip that she prefers plants to people, as they produce fruits and flowers and by their very nature do good.

Her affinity for nature also creeps into her writing in the form of the odd metaphor. In ‘Jelly Sweets’ for instance, a bereaved mother sees her son waving in the movement of a branch. In ‘The Man from the Garage’ a character believes, “Religion is like a tree—it doesn’t matter which one you choose to sleep under; they all provide shade.”

Khanna’s autobiography tendrils through her writings. Putting words on a page, planting a seed in soil are similar endeavours, both create something out of nothing. As Khanna says, “It gives me great joy to see things growing, maybe it’s always been my nature to look at things which are changing, becoming more than what they once were.” With Welcome to Paradise, Khanna has, also, become more than what she once was.