Nayar’s Believe It or Not

Kuldip Nayar's memoirs are a good read. But his apologies and retractions since its publication do justice neither to his book nor his reputation as a journalist

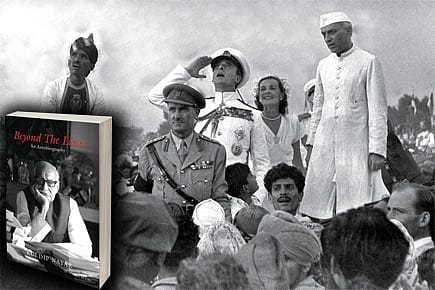

Though it has been called one, this book is not much of an autobiography. If it were, it would perhaps be boring compared to what Kuldip Nayar has written. Beyond the Lines (the unimaginative title is a take on his column, 'Between the Lines', that Nayar says his publisher insisted on) is actually Nayar's India book. And compared to others who've written theirs, 89-year-old Nayar has been a witness to a great deal more.

As a journalist who reported on Gandhi's assassination and saw a string of prime ministers from Jawaharlal Nehru and Lal Bahadur Shastri right up to Inder Kumar Gujral up close, Nayar obviously would have a lot to write about, and he does. He has had a ring-side view of several important events and even been a marginal participant in a few. He recalls how Nehru, weeping inconsolably after Gandhi's assassination, climbed a wall at Birla House, wiped his tears and made this announcement: "The light has gone out of our lives. Bapu is no more…" On another occasion, Nayar recalls MF Husain 'transporting canvases on a bicycle while walking alongside it' and urging Nayar to buy 'at least one' for Rs 100. Nayar says he didn't because he could not afford it then.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

This account is not of a journalist's alone. A word of caution here for the reader: during the period he writes about, he has also been a government information officer attached to India's first Home Minister GB Pant and then his successor Shastri. He was India's envoy to the UK (during VP Singh's regime), a nominated member of the Rajya Sabha (from 1997 to 2003) and a human rights activist, as well as a champion of better India-Pakistan relations.

This book, which comes after more than a dozen others by him, is Nayar's version of the history of modern India—sprinkled with personal anecdotes—beginning just before Partition right up to present times. 'I was conscious that I was willy-nilly writing a contemporary history of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh—countries that I had seen and experienced from the time they came into existence,' he writes rather immodestly.

The account begins with Nayar's early days in Sialkot (now in Pakistan). His narration of the Partition is a personal and emotional account. He describes leaving his home amid confusion, his sense of loss compounded by his parents' belief that they were only going away for some time. Even before the physical boundaries were drawn and the bloodied migration across the Radcliffe Line began, faultlines had appeared in Punjab with Hindus and Sikhs on one side of the divide and Muslims on the other.

The access that the author enjoyed led him face to face with several players in history or those around them. 'Once, when Jinnah was in Lahore, Iftikhar-ud-din, Pakistan's rehabilitation minister, and Mazhar Ali Khan, editor of Pakistan Times, flew him in a Dakota over divided Punjab. When he saw streams of people pouring into Pakistan or fleeing it, Jinnah struck a hand to his forehead and said despairingly: "What have I done?" Both Iftikhar and Mazhar vowed not to repeat the remark. Mazhar took his wife Tahira into confidence and told her what Jinnah had said, and she communicated this rueful remark to Nayar long after her husband's death.'

Nayar interviewed Lord Mountbatten in the early 1970s on the Partition and the mess it left behind, and even Cyril Radcliffe, who had drawn the boundaries as they now exist. Radcliffe told him that Lahore was earlier awarded to India but later re-allocated to Pakistan since the Punjab across the border had no other city worthy of a capital.

Nearly two decades later, Nayar met Lady Mountbatten's nephew Lord Romsey and tried to obtain Nehru's letters to Edwina from him. 'I bluntly asked him one day whether his grandmother and Nehru had been in love. First he laughed and then wondered how he could describe their relationship… Lord Romsey subsequently said: "They fell in love; a kind of chivalrous love which was understood in the olden days. Nowadays when you talk of love, you think of sex. Theirs was more a soul-to-soul kind of relation. Nehru was an honourable man and he would have never seduced a friend's wife."'

Romsey told him that he had given the complete set of Nehru-Edwina letters to Rajiv Gandhi, and it was now with the Nehru Memorial Library in New Delhi. When Nayar approached the library, he was asked to seek permission from Sonia Gandhi. He wrote to her a few times, but nothing came of it.

The author also describes Nehru's darker side. In the case of Kashmir, for instance, Nayar writes that his Kashmiri origins clouded his judgment and he stood in opposition to Vallabhai Patel's view that Kashmir was best left to Pakistan. The author suggests that India's war with China and subsequent defeat was brought about by Nehru's faulty beliefs: one, the Chinese would not retaliate if the Indian Army tried to evict Chinese soldiers from the posts they had built on Indian territory, and two, that the Indian Army was well equipped to fight the Chinese.

The book deals extensively with the Punjab problem. Nayar writes that Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale was a creation of the Congress, a brainchild of Sanjay Gandhi. 'It was Sanjay Gandhi, known for his extra-constitutional methods, who suggested that some 'Sant' should be put up to challenge the Akali government.' He goes on to quote Union Minister Kamal Nath to say that interviews were held to select the right candidate.

'Kamal Nath,' writes Nayar, 'recalled: "The first one we interviewed did not look a 'courageous type'. Bhindranwale, strong in tone and tenor, seemed to fit the bill. We would give him money off and on, but we never thought he would turn into a terrorist." Little did they realise at [the] time that they were creating a Frankenstein.'

The book also alleges that the All India Sikh Students' Federation (AISSF) president Amrik Singh, who died during Operation Blue Star in June 1984, was an IB agent who went by the pseudonym 'Falcon'. It was an open secret, says Nayar. The bit about Bhindranwale is not new, but Amrik Singh's IB connection is an important revelation, if it indeed is true. Yet, after protests by groups in Punjab that have little or no mass support, he has been quick to apologise and has even declared that the bits about Bhindranwale, Amrik Singh and Dal Khalsa (which he claimed was set up under former President Zail Singh to counter the Akalis) would be taken out of the book.

"I have a long history of activities and writings in this respect. I have no intention to hurt the sentiments of anybody," he said in a recent statement. "As such, I have decided to delete the portions of my autobiography on which objections have been raised. These parts shall not be there in the next edition of the book. Even then, if I have hurt the sentiments of anybody, I feel sorry and apologise for the same."

The book is barely out and Nayar has already apologised twice for what he records in it. For instance, he wrote that a newspaper editor who once worked under him had become unduly affluent. Once that stirred a controversy, he was quick to tender an apology.

Such feeble retractions only leave the reader confused. With these retractions, the author also does injustice to the journalist Kuldip Nayar, the professional who was censored and even detained by the Government during the Emergency, only to be released by a court which pronounced that he was 'a dedicated journalist with no affiliation to any political party'.