Natural Instinct

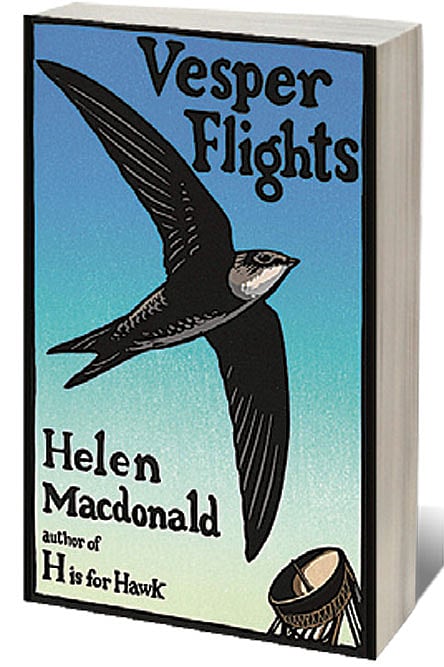

‘I CHOOSE TO THINK that my subject is love, and most specifically love for the glittering world of non-human life around us,’ writes Helen Macdonald in the introduction to her recent collection of essays Vesper Flights. In her memoir H Is for Hawk (2015) Macdonald told the story of training a hawk to tame her grief after her father’s sudden death. While the book poured out from a wound, it also established Macdonald as a nature writer of standing. Vesper Flights is once again firmly rooted in the wild and pulses with an uncommon understanding and respect for the natural world around us.

It is the kind of book where, on the one hand, you want to treat each chapter like a sacrament, something which must not be rushed and must be bestowed with reverence, but, on the other, one also wants to plough through it from beginning to end in uninterrupted sittings because to leave its world is to return to an

impoverished one.

A reader remains invested in first-person essays when the author is interesting. And Macdonald has an arsenal of anecdotes and experiences to hook anyone. Her tales are odd yet compelling. She is allergic to dogs, horses and foxes. She can be felled by migraines. Back in 1997, she worked at a falcon conservation-breeding farm in rural Wales seven days a week, for four years. Once when she found a wounded ostrich that could not be saved, she bashed its head with a rock to knock it out, and then cut its throat with the only instrument she had, a keychain penknife. She writes of how as a child she’d clean and polish fox skulls and keep the wings of road-killed birds. As an adult she finds a swift by the River Thames and unsure of what to do with it, swaddles it in a towel and tucks it into her freezer. She learns she is allergic to foxes, while skinning a road-killed fox to turn into a rug. Who would not want to hear the stories she has to tell? Who would not want to walk with her in the woods?

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

Much of nature writing can be read in the baritone of David Attenborough. It is a language of either pristine nature in which humans have no place, or it is a man-versus-wild scenario.

Macdonald’s writing stays clear of these pitfalls because it is so deeply inked with empathy and wonder. As a loner child who found company in the wild, nature is not something to be conquered nor does it exist for man to discover himself. Nature to her is, above all, a place where she seeks ‘intimacy and companionship’.

To her work she brings both a scientific temper and a spiritual bent. The natural world is to be appreciated through the lens of science as that reveals that we ‘are living in an exquisitely complicated world that is not all about us’. Macdonald also confesses how while writing her memoir she often found the secular lexicon inadequate. In this book, she realises that the language she needs is most often used for writing about religious experiences. In nature’s ‘small’ occurrences she sees the divine, whether it is the sight of a hill through clouds or hailstones at one’s feet. In these moments she feels a numinous consciousness.

In the introduction, Macdonald writes, ‘I hope that this books works a little like a Wunderkammer. It is full of strange things and it is concerned with the quality of wonder.’

This collection is precisely that. It overflows with insights and details which the reader will wish to pass onto others. For example, did you know that only female glow-worms cannot fly but emit a light to attract the smaller, winged male? Once mated, the light is extinguished, they lay 50-100 small eggs and then die. Or that disoriented by city lights more than a hundred thousand birds die each year in New York itself? This is ultimately a book about grief and birds, love and death. What could be more essential for all time?