Nation on Trial

IN 1905, WHEN the British partitioned Bengal, the nephew of Rabindranath Tagore, painter and writer Abanindranath Tagore, created a painting inspired by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s famous patriotic novel Anandmath. Bharat Mata, depicted as a serene-faced woman clad in saffron, holds in her four hands a sheaf of paddy, a rosary, a book and a piece of cloth. Bharat Mata soon became a potent symbol of nationalism, a rallying point for freedom fighters around the country.

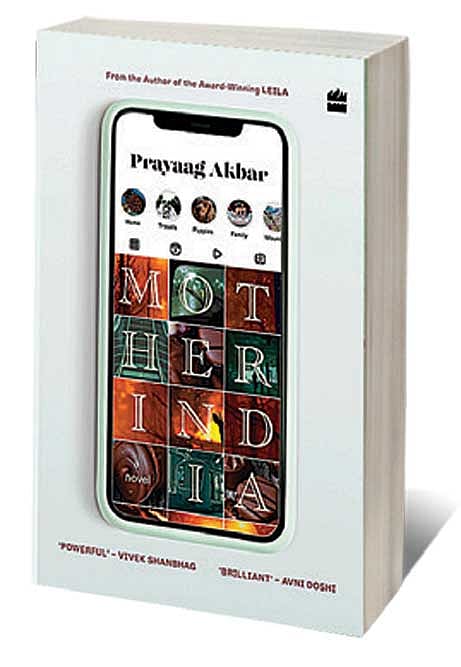

And today, more than a century after she was first created, she is much more than a painting. Bharat Mata is, as Prayaag Akbar describes her in his novel Mother India, “… the vision of pamphleteers, calendar makers, magazines and journal illustrators, people practising their skills at home…” A symbol to be used to whip up a frenzy of nationalism. To manipulate, to influence.

It is one of these influencers who initiates the action that forms the core plot element of Mother India: Kashyap, whose catchphrase, “You can’t handle the truth!” exemplifies his ethos: the in-your-face, belligerent and confrontational style of egging on his followers—in this case, to come to the rescue of a beleaguered Bharat Mata, assaulted by Muslims. Kashyap’s assistant, Mayank, uses artificial intelligence to generate an image of Bharat Mata. AI must be fed reference images to create a plausible Bharat Mata, and the woman whose image Mayank uses as reference is a stranger he follows on social media, Nisha Bisht.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

From here on, the story progresses, moving between the alternating perspectives of Nisha and of Mayank. Nisha, who works at a Delhi mall showroom for an elite Japanese chocolatier, is having an affair with her boss Siddharth, and who keeps in touch with her family back home in Uttarakhand. And Mayank, tracing his lineage back through many generations born and brought up in Delhi’s Mahipalpur, struggling to make sense of all that surrounds him: the relentless push-and-pull between tradition and modernity, between development and roots, heart and mind.

Akbar sets his story in today’s India, today’s world: a world that lives online, where fortunes are made, and lives wrecked online. The dichotomies that surround us and with which most of us grapple come vividly to life here as Nisha and Mayank individually try to come to terms—with themselves, their consciences, and the world around them.

Mother India’s story is well-told, the characters sharply etched (equally sharply etched is Delhi itself, a setting powerfully evoked). The conscienceless, brutal desire to get ahead, whether in the form of Siddharth’s ambition, or Kashyap’s; the way gullible crowds are manipulated; the insularity, harshness and hate that has become the norm in India today: all of it comes through in a way that is even more frightening because it is so relatable.

In a story about the nation as mother, Akbar subtly brings up the symbol of motherhood—there are mothers aplenty here, whether human or animal. Mothers, too, who may not always be the pure, long-suffering symbols of chastity one associates with Bharat Mata. There is a mother here, a widow who risks shame (and, worse, is shamed) for the sake of her child. There is a would-be mother who is relieved to find that she may after all not become a mother. There is a stubborn mother, whose son defies Bharat Mata herself. There is even a dog-mother, a mongrel bitch who abandons her puppies. Are these—perhaps ‘substandard’— mothers worthy of Bharat Mata? Are they, too, after all, worthy of empathy?

As Nisha, in Akbar’s searing words, thinks: “Maybe that is what we mean, when we call the nation mother. We crave the sustenance of her breast. But whatever she gives is not enough. We keep drawing. We never rest, for we fear there is a sibling who receives more.”

Intelligent, thought-provoking and courageous, Mother India is a novel that reflects our turbulent times all too brilliantly.