Mumbai to London

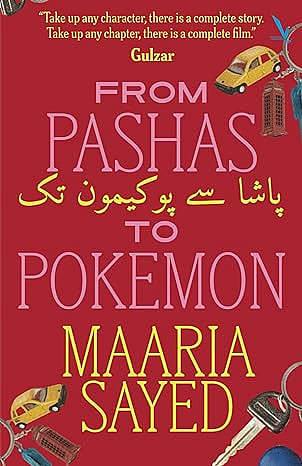

Identity, what it means to us and our place in the world are common questions, and so are constant themes in literature. These questions are explored in filmmaker and screenwriter Maaria Sayed’s first novel From Pashas to Pokemon, from the perspective of Aisha Khatib. It’s a question Aisha asks herself all her life.

Sayed’s depiction of Aisha’s home in Mohammad Ali Road colony in Mumbai, her ties with her loving, close-knit family, extended family, and neighbourhood are not only the backdrop of Aisha’s story, but they also help demonstrate what it is to be Muslim in post-liberalisation India. A part of this are the casual slurs Aisha deals with, including those which are not intentionally offensive. “Of course, Muslims must have their meat, isn’t it?” “But you people are so fair, just like Kashmiri Pandits.” However, Aisha is always aware of how privileged she is. She is very sheltered and spends her summers in a Delhi bungalow, her parents do not lack money, and her father encourages her education. He puts her in an English-medium school and tells her, “The way of the world has changed… I don’t want you to be left behind the way I was left behind because of my Urdu education.” The narrative jumps back and forth in time, to Aisha as a precocious, observant child in Mumbai in the early 1990s, to an increasingly introspective adult studying in London in the early 2010s, to her years back in Mumbai.

Though larger political events are only referenced in passing, they also have a bearing on Aisha’s worldview, as she is a cosmopolitan, educated, privileged millennial growing up in independent India, a relatively new nation state with a complicated history. Her grandfather, for instance, an active political figure in the freedom movement tells her after her return from London, “When I look at my grandchildren who willingly consume everything as long as it has the tag Made in America or Made in Britain, I know I need more time… I want you all to be proud of your roots.” For her part, Aisha feels her connection to her roots isn’t lacking. As she says, “Our love for the country is linked to our bonds with the warmth of our families… We didn’t feel as patriotic then because we were more connected to the world at large, with international brands and Hollywood films.” In the same way, for “a girl raised in a moderately religious Sunni Muslim household on Mohammad Ali Road” Aisha has less of a religious identity than the previous generations, having attended an English-medium school with children from all faiths, with strict Catholic nuns.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

The novel also deals with questions of sexuality, gender and class. The issue of class is seen through Aisha’s interactions with her Bihari driving instructor, Mister Pande. He is a colourful character, who slyly but humorously teases Aisha about her education and Western exposure, comparing it to her inept driving and highlights Aisha’s own prejudices. As she admits, “There is an unspoken reservation in the hearts of some Mumbaikars towards a driver from Bihar. …They cause a mess in our city by being party to petty crimes and brawls.”

Sayed’s depiction of Mumbai through Aisha’s eyes is a love letter to the city, with all its chaos, overcrowding, and diversity. Her descriptions of her years in London as an outsider and a woman of colour are equally poignant and authentic. It is evident that the novel springs from her own experiences of growing up as a privileged Muslim in India, her education in London, and her own struggles between the pull of different generations, and between East and West, which is mirrored in the title. As a young, award-winning filmmaker, one can gauge her knack for telling a story in her debut novel. Although the jumps in time are at times jarring, and the book only picks up pace only after the first 30 pages, the writing is otherwise smooth and engaging, and her characters are relatable and have depth. And the questions she asks are profound and relevant.