Mad with Love

THE CHANDAYAN IS a long love story, a premakhyana, from the Tughlaq period in the 14th century. Hardly unique in form and content, it is one of many other such love stories that live within the uncomplicated pleasures of a folk tale (however tragic) as well as in the rich and complex allegories of spiritual traditions, most particularly Sufi ones. In northern South Asia, we are familiar with such stories of tragic love as Heer Ranjha, Sohni Mahiwal and Mirza Sahiban, among others. They speak of lovers separated because of caste and class and religion, or by family feuds within the same community. But from the second millennium CE, many of these tales were transfigured into stories about the separation between the human soul and the divine, and became embedded in the Sufi repertoire.

It is commonly held that the archetype, the paradigmatic version of this tale is the Arabic story we know as Laila Majnu, which was in circulation probably as early as the seventh century CE. A pair of young lovers is kept apart by their families and while Laila pines quietly in her secluded life, Majnu goes mad with love, wandering in the desert and reciting poetry to birds. Laila soon dies of a broken heart and Majnu is found dead by her grave, his last verses of poetry scratched into its walls.

This sweet sad story proliferated and entered early Sufi practices in the nascent Islamic world. Majnu’s passion, his unrelenting commitment to his lost love, becomes the model of the human seeker, with a soul that longs to be reunited with its beloved, the divine. In the 13th century, the Persian poet, Nizami, pulled together both secular and spiritual versions of Laila-Majnu and gave it the form we know best. His work reached the northern sub-continent through the Islamicate courts and became a genre of its own, producing, in the next century and a half, such multivalent and highly localised poems as ‘Chandayan’, ‘Mrigavati’, ‘Padmavat’ and ‘Madhumalati’. The composition of these poems created a literary vernacular that eventually became modern Hindi. The compositions also occupy the critical moment of transition from oral to written story telling. It goes without saying that these newly purposed stories, their intent, their authors and their audiences speak eloquently about a composite culture in our past, an important historical reality that is now being heavily contested. The publication of this book provides us with a timely reminder about the sub-continent’s deeply rooted syncretic culture, amply demonstrated by the fact that some of the illustrated manuscripts of The Chandayan use both Nagari and Urdu/Persian scripts.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

Chandayan is originally a folktale from central India, told by many traditional communities, each situating the story in their own milieu and inflecting it with their own practices and customs. Though details vary, the basic story goes like this: beautiful Chanda is married off to an unattractive man in another village. She discovers he is impotent and heeds her mother’s advice to return to her own home. When she resumes her old life, a bard sees her and begins to compose songs about her incomparable beauty. He reaches the neighbouring kingdom whose ruler, Rupchand, falls in love with the woman of whom the bard sings. Rupchand sets forth with a massive army to capture Chanda. Her father places her in the care of a young bodyguard, Lorik. Chanda and Lorik fall in love and run away together, far from their homes, their spouses and their families. In the heart and hands of Mulla Daud, who was closely connected with the Chishti saints of Delhi, the story of Chanda and Lorik becomes a Sufi allegory in which the painful separation from the human beloved is transformed into the unbearable separation from the divine. But, for the Sufi allegory to be fulfilled, the story needs to speak of renunciation and abandonment. In many (some say all) versions of the Lorik-Chanda story, Lorik becomes an ascetic, a yogi when he is without his love, akin to Majnu’s desert wanderer. In other tellings, the pining lover is Maina, Lorik’s wife, whom he abandons when he runs away with Chanda. The trials and tribulations that the runaway lovers face are symbolic of all the worldly attachments the seeker must shed in order to reach the divine.

While the poetry of The Chandayan and the paintings that accompany the verses sit squarely within the aesthetic styles and tropes that we expect from other Indic texts and pictures, the folk elements that underpin this great spiritual allegory provide some wonderful surprises. Chanda’s maidservant, playing the part of the classical ‘sakhi’, has gone through some trouble to engineer a meeting between the lovers. Lorik climbs up to Chanda’s bed chamber with a rope ladder, but she is startled and grabs him by the hair, mistaking him for a thief. He bursts out “Listen, you thoughtless flaming faced girl. In my entire life I have never stolen anything. O Cowherdess! I have come because I love you. But you call me a ‘thief’ and curse me... You are grabbing my hair and summoning people; they are sleeping, why are you waking them? I am not interested in your alarms, I have been deceived by your good looks.”

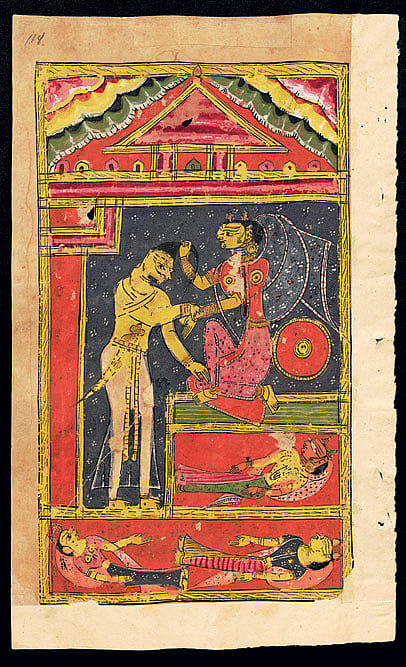

IN THIS RATHER earthy verse, our pining lover speaks with a charming (if impatient) frankness to his beloved— not quite the language we are accustomed to from other longed-for reunions in our classical texts. Look also at the images that accompany the verse—they come from two distinct styles. The one on the left is in the so-called “Jain style” and the other is likely to be from somewhere near Mandu. The Jain style is robust with strong lines and colours: Chanda has a strong grip on Lorik’s hair and the painting seems to respond in mood and tenor to Lorik’s frank and direct speech. The image from the Mandu region of the same narrative is presented in gentler pastel shades, our heroine also appears to be more delicate, almost as if she were stroking Lorik’s head instead of yanking at his topknot.

This is a truly glorious book, full-blooded in both its images and its accompanying texts. It is marvellously produced, each picture a little jewel in itself, and a companion text, essays and a translation, that illuminates not just these jewels, but the larger ornament, The Chandayan. The essays (by Naman Ahuja, Vivek Gupta and Qamar Adamjee) are wonderful, providing a wealth of aesthetic and linguistic detail and yet, situating the poem and the paintings in an important larger context. The easy tone of Cohen’s translation is a pleasure to encounter, he captures the immediacy of the folk narrative as well as the abstraction of the story’s higher aspirations.

This volume reminds us (those who are old enough to remember), how very important Marg was as a magazine in the world of art history and culture and how very precious their special editions were. Having said that, this is a book that I had to read standing up—even placing it on a desk to sit and read was uncomfortable and unsatisfying in terms of appreciating the images. Nonetheless, I am very pleased to own it and slowly find ways to enjoy it more easily.