Where Life and Death Coexist

In Varanasi, writes Diana Eck, death comes as no surprise. The processions here include the processions of death. Death is not feared in one of the world’s oldest living cities, but welcomed as a “long-awaited guest,” notes the scholar of religious studies.

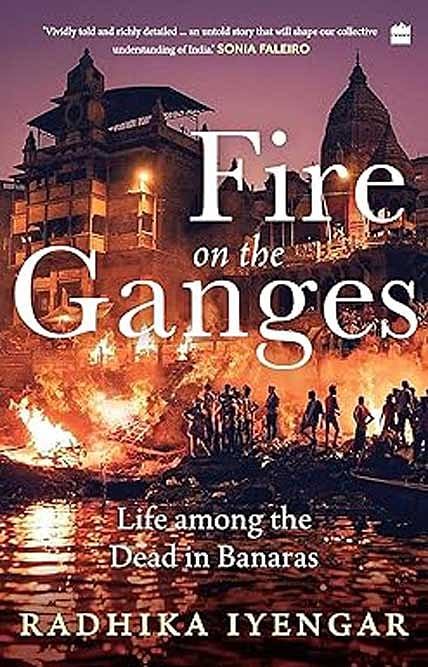

Eck talks about the sacred city’s famed Manikarnika burning ghat, a place alive around the clock, which “combines the awesome with the beautiful”. Smoke from the pyres entwine with temple spires, casting a white shroud that lingers above the ghat.

Then there are the Doms or the untouchables, who control the cremation ground. They tend to the corpses secured on bamboo stretchers from the moment the flames are ignited until only ashes remain, earning a compensation for their service. “The deceased is honoured as would befit a god, and in Kashi [the other name of Varanasi] it is said that the dead take on the very form of God,” writes Eck.

Radhika Iyengar’s Fire on the Ganges, departs from the spiritual landscapes painted by scholars such as Eck, and ventures into uncharted territory. She agrees “in the land of the dead [in Varanasi] there is life all around,” and it is here “death asserts itself as the last witness to life”.

Iyengar then puts on her journalistic lens for a forensic examination of the harsh working conditions at the ghat, and a vivid telling of lives of the Doms who inhabit it. For that alone, her work deserves attention.

Iyengar writes about the “debilitating and torturous” working conditions at the ghat in graphic—and important—detail. Under a rotational schedule devised by the relatively affluent within their ranks, the Doms endure gruelling 16–20-hour shifts, four to 11 days at a stretch. In a day a Dom typically cremates three to five corpses earning around 150 rupees for each service.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

A corpse takes about three hours to turn to ash. Some—mauled by long illnesses—take even longer. “All the wood will burn, but the skin won’t melt,” a Dom tells Iyengar. “It makes us work doubly hard”.

Not surprisingly, the Doms live a life of abject hardship and distress. Drug-addled children run along the ghat, stealing shrouds covering the dead to make money. The men work in the proximity of heat and smoke and suffer from extreme exhaustion— “strong winds scorch their skin and hair”. Then there are the “ash-shifters”, washing bones and ashes and combing through the remains to salvage gold and silver.

“It is the sight of melting flesh that is revolting,” says a Dom. “That is why most Dom men drink alcohol and chew gutka. We kill our senses before getting down to work”. That is also possibly why Dom men die at an early age, Iyengar writes.

Iyengar follows the lives of a small group of men and women to explore caste, patriarchy and aspiration in Chand Ghat, a community ghetto, not far away from the ghat. Among them are a man who leaves the ghat to study in a private university, a matriarch who makes peace with her fate—“I have never spoken to anyone outside my community, I know my place”—and a spunky widow. The state of women is worse, “there is not a single girl who has studied beyond eighth standard,” a girl in the ghetto tells Iyengar.

Fire on the Ganges is an apocalyptic tale of the wretched lives of outcast people without whom, for many Hindus, there is no moksha or liberation from the cycle of rebirth. Yet, amid the sombre narrative, a tale of hope and ambition unfolds: an increasing number of Doms are now daring to defy social norms, getting educated and leading life on their own terms. More parents are sending their children to school. “Living in that mahaul, (environment),” says a Dom, “you cannot do anything.”

“You have to leave. You have to get out of here.”