Lady with the Lamp

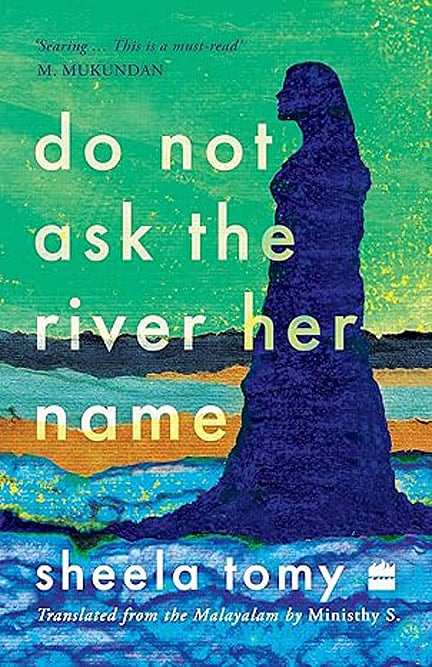

Though the backdrop of the Israel-Palestine conflict drives the plot of award-winning Malayali author Sheela Tomy’s new book, the themes of displacement and the plight of refugees are at its heart. Do Not Ask the River Her Name, translated from Malayalam to English by Ministhy S, is mainly told through the eyes of a neutral observer in the centuries-old conflict, the Christian Malayali nurse Ruth Esthappan.

Ruth is a nurse caring for David Meneham, and when the novel begins in 2021, she has been living with his family in Nazareth for some years. The two other protagonists are Asher, the son of the Meneham family, and his close friend Sahal, a young Palestinian poet. Asher is a compassionate young man who feels appalled and helpless seeing the tension and injustice around him. Sahal, whose family and home were destroyed by bombs as a child, takes an active role in protesting the brutality. Ruth also increasingly becomes less passive and dispassionate. After her husband was bedridden, she works abroad to pay for the bills, and her teenage daughters’ education, and reaches Israel after a harrowing journey via Riyadh and Dubai. She is representative of the numerous Malayali caregivers who must travel across Asia and the Middle East to work to support their families back home. Tomy implicitly makes clear that the contributions of these women for their families are overshadowed by Indian men doing the same thing, in fiction and other media.

Although the conscientious Ruth never forgets what brought her to Israel, she cannot shut her eyes to its reality. Settling down quickly with the kindly Menehams, she finds a community of fellow Asians working in Nazareth. They encourage her to start a vlog of what she sees in Israel. Against the background of the constant unrest and the undercurrents of violence overseen by the harsh and vigilant authorities, she films and comments on the sites and roads in Nazareth that are featured in the Bible. Through her vlog, she and the reader realise that the violence of the past repeats itself. While she has her share of bitter experiences, and is a temporary exile, she soon admits, “Sobbing over a bruised finger in the land of bullets? Goodbye, my sorrows.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Other tools that the author uses for her commentary are seen in characters such as the Meneham patriarch David, and Auschwitz survivor Naomi Bergman. David—like Asher, is used to provide a Jewish perspective that is left-wing—is not fiercely Zionist, and feels that Palestinians are unfairly treated as refugees in their own homeland. He encourages Ruth, telling her, “If you are hampered by the terrors from the past, you cannot move forward effortlessly.” Likewise, Naomi Bergman is a Jewish character who establishes the NGO Denying to Be Foes, so Jews and Palestinians can work together peacefully, and who “vehemently opposed the unspeakable brutalities of occupying territories forcibly.”

This novel has themes which are enormously relevant, but it was written much before last October. As a Malayali who has lived and worked in the Middle East for two decades, Tomy shares in her author’s postscript that while she had been researching the trials of female Malayali caregivers working abroad for their families, a Palestinian colleague recounted how she had been a refugee during her childhood after her city was bombed. One can see how the narrative of refugees in their homeland overshadows the one of exiles abroad.

Tomy’s book is lyrical and poignant, and its themes make it painful and shocking. The shifts in the characters’ perspectives, the occasional use of the vlog, the jumps between the present and Ruth’s life in Kerala, her journey, and the present, her thoughts on the Bible, give the novel a dream-like, and somewhat disorienting quality. In other places the pace is tense and urgent, and the gaps between several characters’ journeys is jarring. The novel’s message, its themes of shared suffering, universal humanity in unexpected places, and the authorities’ brutalities is a little heavy-handed and repetitive, but its protagonists’ journey and quick pace make this ambitious second novel a worthwhile and powerful read.