Khaki Capers

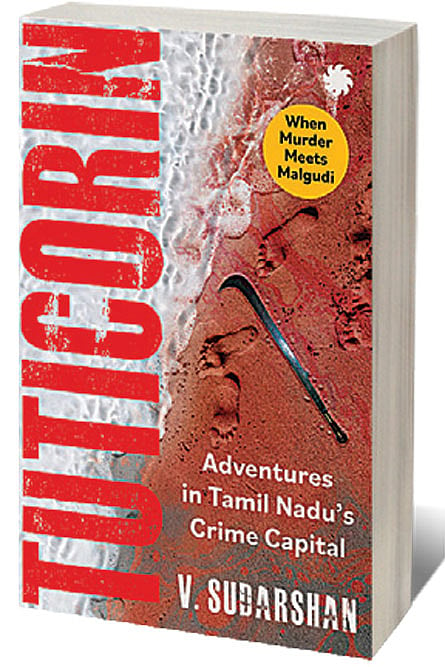

TRUE CRIME IS in an interesting place right now, across mediums. In terms of market demands and therefore sheer volume, there’s probably no better time to be writing a true-crime story, making documentaries and/or scripting features inspired by accounts of real-life crime. But as it so often happens, a genre’s ongoing surge also means there’s a lot of sensationalist products out there; some of them even exploitative (see Netflix’s recent Jeffrey Dahmer miniseries, for example). For my money, some of the best and most interesting examples of the genre share broad similarities—journalistic rigour, a strong sense of place and a certain sociological inquisitiveness in the writing. Journalist and author V Sudarshan’s recent book Tuticorin: Adventures in Tamil Nadu’s Crime Capital (Juggernaut; 304 pages; ₹499) has all of these qualities and a distinctive sly wit for good measure.

The book collects 20 stories from the life of Anoop Jaiswal, an honest and forthright IPS officer with unconventional methods. Through the 1980s, Jaiswal was posted in Tamil Nadu, where he encountered a rich, diverse, and fascinating set of characters—comically superstitious constables, reformed murderers with hearts of gold, opportunistic politicians, grandmothers with steely resolve. As he negotiates one crisis after another across the book, we also witness the evolution of Jaiswal himself, the cop from Uttar Pradesh who learns Tamil slowly but surely, who wins the heart of ordinary people through humility, patience, hard-nosed pragmatism, and a sense of fairness.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

During a video interview, Sudarshan spoke about the making of this book, and his initial impressions of Anoop Jaiswal. “My first impression of him was that he was perhaps the most unconventional officer I had ever met, a real maverick,” Sudarshan says. “He used to speak his mind—which means that I, a journalist, could often not print a single word of what he was saying. But at the human level, we connected and we got along very well.”

One of the first things you notice about Tuticorin is the distinct lack of hero-centric narratives. At no point does Sudarshan lionise Jaiswal outright. Even on occasions when crowds of people have thronged to express their gratitude, the author downplays the emotional tenor with humour. This is a refreshing change from the chest-thumping that mars law enforcement stories all too often. Instead, Sudarshan focuses on practical issues, like the fact that Jaiswal’s Tamil was rudimentary at best when he was first posted in Tuticorin. He had to rope in various officers to translate on the fly. And then, of course, there are the all-too-familiar problems that one would expect most civil servants to face in India—political interference, rigid hierarchies, the tacit expectations of unthinking obedience.

In fact, Jaiswal began his IPS career after successfully appealing his unfair expulsion from the National Police Academy (NPA) in Hyderabad, where he was a cadet officer in 1981. As Sudarshan mentions in the Foreword, the matter became a landmark Supreme Court judgment (Anoop Jaiswal vs Govt of India, 1984). According to the author, this was “essentially as punishment for merely being unconventional and questioning the system during training”. Across the course of Tuticorin’s 20 stories, we see Jaiswal at odds with politicians on both sides of the aisle, to say nothing of his own superiors.

During our conversation, Sudarshan points out that police officials are not immune to the attractions and compulsions of power. “It’s not as if this is restricted to law enforcement; in every field, proximity to power is seen as necessary for career progression,” he says. “But we expect policemen to be made of sterner stuff than other people, we expect them to be fairer; I don’t know whether this expectation is fair or unfair. We expect that there shouldn’t be a single crooked bone in their body, when we know that all the bones in everybody’s bodies are totally crooked, all of them.”

There’s a good balance here, in terms of tonality. A few of the stories have a high body count; in one case there’s a family of four bludgeoned with machetes for example. But these have also been balanced by softer, much more whimsical accounts in Tuticorin (a smart decision on the part of both writer and editor).

My favourite among these is a 10-page narrative called ‘Post Paid,’ which has the plotline of a classic O Henry short story and the style of cinema verité. As the author admits in the Foreword, the Sahitya Akademi Award-winning Odia writer Manoj Das heard the facts of the story from Jaiswal and was moved enough to want to write it himself. Sadly, Das passed away before such an effort could come to fruition and so, it fell upon Sudarshan to tell this story. A woman in her late 80s travels with great difficulty to see Jaiswal; she wants him to do something about her unthinking relatives who are not taking care of her as they promised to. During their conversation, Jaiswal discovers—by accident—that she was owed a widow’s pension since the 1920s (which is when her husband, a policeman, died).

“There are a few things that make this story so compelling,” Sudarshan says. “One is the old lady at the heart of the story, she is 87-years-old with one-and-a-half feet in the grave. We don’t know whether the old lady finally has some semblance of peace in her final days. The circumstances she finds herself in and the gruelling 100-km journey she undertakes to meet Anoop Jaiswal are also remarkable. There’s a brutal honesty to her story and it reveals the weaknesses in the system. Jaiswal had to involve the forensics department to verify her late husband’s credentials.”

In between the mass murders, the illicit liquor rings and various other horrific crimes, there are even a few family moments involving Jaiswal, which imbue the book with strategic bursts of levity. His four-year-old daughter turns up at Jaiswal’s office one day with an official complaint to make— namely, that her father never comes home on time. IPS officers are also frequently transferred, which means that his children have to change schools with the same frequency. The challenges before Jaiswal’s wife Neelam and their children were considerable, despite the (relative) stability of a government job.

“I have been to the house allotted to his family at the initial stage of his career,” Sudarshan says. “It was a one-room house with an attached kitchen and bathroom. I still have pictures of the house on my phone. It must have been extremely challenging for Mr and Mrs Jaiswal, especially since Anoop’s parents would also stay with them during that period, in Ambasamudram (Tirunelveli district, Tamil Nadu)”.

Towards the end of Tuticorin, when we meet Jaiswal in late-career dotage, the tone of the book becomes philosophical, almost wistful, as though acknowledging the journey readers have just undertaken with this man. As Sudarshan writes in the final chapter; “Long ago he had bought three acres of land near the battalion, dreaming that someday he would build an ashram there, a stone’s throw from the mango grove with the parrots, and the garden where butterflies hung heavy in the air between the flowers, there, by the Manimuthar dam, amidst the teak trees, nestling in the shade, the wind rustling through the leaves and the tall grass all around, and not far away the clack of the drill sounds drifting from the 9th Battalion parade grounds.”

Tuticorin is a cleverly written, fast-paced and entertaining read. These stories—some of which will linger inside your head long after the last page has been turned—are well worth your time, irrespective of your interest levels in true crime.