Kabul Falling

THE CHAOS SURROUNDING the US’s withdrawal from Kabul in August 2021 recalled other imperial retreats in history. The fall of Saigon in April 1975, which ended a long US misadventure in Vietnam comes most immediately to mind. The US endgame—if it can even be called that—in Afghanistan had climaxed on August 15, 2021 as the Taliban marched into Kabul and the older government and administration just melted away. That date itself recalls another imperial retreat—the British from India in 1947—where elaborate and carefully designed ceremony cloaked what was in effect a disorderly withdrawal alongside a communal bloodbath amidst an administrative breakdown. In Kabul there was no ceremonial retreat. The consensus was then, and it has since remained, that the end of the US’s longest military engagement was a rout.

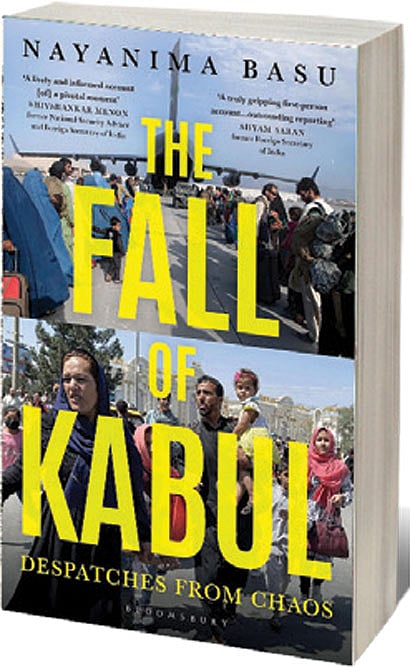

The journalist Nayanima Basu was in Afghanistan that fateful August. Basu’s editors were supportive but, incredible as it may sound, she went alone and throughout her stay appears to have relied on casual contacts and local guidance. She was without even a camera person (who was not issued a visa) so she did both the filming/recording and the reporting. At a time when all bets on Afghanistan were being called off, hers appears largely as an individual enterprise. The dangers were well known. The Indian photojournalist Danish Siddiqui working for Reuters had been killed by the Taliban just a few weeks earlier. Basu decided to go ahead in the face of advice that she was embarking on a reckless venture.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Arriving in Kabul she was confronted by two contrasting frames—of hopelessness and despair, and of confidence which as it turned out was misplaced. On the one hand: “I began to sense the depression lingering in the air. Kabul, at the moment, looked like something straight out of the pages of a historical dystopian novel, where everything seemed to be in an existential crisis.”

On the other hand, despite the reports of the Taliban’s advance across Afghanistan there remained many who were dismissive about any possibility of a Taliban takeover. There was certainly a residual confidence among some that the US had a card up its sleeve by way of which some power sharing agreement, no matter if only face saving, would be worked out.

Basu’s account of her stay in Afghanistan is directly written. She does not make any effort to over dramatise the situation—which, such as it was, needed no embellishment. Her descriptions of her stay, of the general sense of uncertainty and the mood swings, the glimpses of a false bravado of those still in power all make for a gripping first-person account.

In this tense situation when an older power structure was simply melting away Basu also made her way to Mazar-i-Sharif two days before it was taken over by the Taliban. Commercial flights were operating which also conveys something about the nature of the transition underway in Afghanistan. This was a Taliban takeover which was going to be different from the violent destructive civil war that had accompanied their earlier seizure of power. Even more remarkable is the fact that Basu decided to travel by road to Kandahar on August 14, the city was then already under Taliban’s control. She returned midway amidst reports that Kabul would soon be surrounded and returning then would be impossible.

Basu departed Kabul on a flight, which evacuated the Indian Embassy personnel. Her descriptions of the final hours are a riveting account of the confusion, fear and panic that gripped many. The scenes around Kabul airport as Basu struggled to join those being airlifted back by the Indian Air Force give a clear sense of the risks she undertook for this assignment.

In a useful epilogue Basu details the current geopolitics surrounding Afghanistan, the role of different powers, the nature of Taliban 2.0 etc. The strength of the book however is the direct reportage of a complex and dangerous situation and how a gutsy journalist functioned in those circumstances.