Joy Rides

Confession time. I’m a confirmed member of the tribe of moderns who, like Rajat Ubhaykar, thinks it a great idea to chuck up one’s job and go hitchhiking, vagabonding, or simply drift about in some uncommon manner—so I fell for this book even as I was reading the foreword. As a child, taking a long trip with his parents, Ubhaykar recalls ‘being struck by a sort of epiphany, that India is bigger than the boundaries of my imagination, or anyone’s, for that matter.’ It sounds like a rationalisation, but he probably needed some such idealistic justification to give his family when, as a rookie journo in his early 20s and busy climbing a career ladder in Mumbai, he decided instead to spend the better part of a year riding around India with truckers—to, as the saying goes, ‘write the book you always wanted to read’.

The result is a delightful romp of a reportage. The adventurous Ubhaykar often sleeps sitting up or when the opportunity arises catches a nap in a bunk bed at the back of the driver’s cabin, has a bath when there’s an occasion for it, cooks roadside meals with the crew or shares food at cheap dhabas and, well, roughs it out in every imaginable manner. And it is an epic journey, to say the least. From Mumbai he heads north via Gujarat and Rajasthan to Kashmir, then steers east beyond the chicken-neck of the country all the way to the troubled Nagaland and Manipur borderlands, before he undertakes the last leg of his tour south via Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, where he eventually traverses Tamil Nadu and reaches land’s end at Kanyakumari.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

However strenuous it may seem, it’s often a fantastically fun-filled trip—pegs and anecdotes are shared as pendrives filled with music come out when they break for the night. At other times, it gets scary—rebel groups in the Northeast, who openly run administrations parallel to the local governments, block highways to extort informal road taxes and smash the windshields of lorries if they don’t get cash. He also witnesses the depressingly widespread corruption that drivers must handle on a day-to-day basis (there’s talk of bribes filling ‘gunny bags’ at check posts) and he encounters policemen who have, in one case, a ‘giant posterior and corrupt demeanour’. For their part, the drivers are sometimes high on drugs like opium (the ‘organic variety’ called bhukki, mind you) that keeps them driving stoically without taking breaks for food or drink. And Ubhaykar is stunned by gay paedophilia at the shadier dhabas.

Yet this book also dispels the sweeping notions one may have got from reading reports on the sordid side of trucking—for example as a dispenser of HIV—and other exaggeratedly negative impressions of truck drivers being a health hazard to other motorists, since pretty much all the drivers whom Ubhaykar hitches rides with are surprisingly homely and safety-conscious types. Even if they spend almost all of the month on the road to keep the nation running, and its populations’ larders filled with fresh agrarian produce, they take home their salaries more or less intact to support their families, often residing in villages or small towns, a few of which Ubhaykar visits.

Even the truckmen themselves, whom our hero discusses all matters with, are fed up with what they consider an undeservedly nasty reputation. One of them says that when his father started in the business in the 1980s, the transport worker’s status was high (‘Doctor ke barabar maante the’) because ‘driving trucks was considered a relatively skilled, well-paid job, much like crane and forklift operators now. Villagers, largely cut off from the world, would welcome them as the harbingers of goods and news, treat them to tea, and even invite them to their homes.’ At the end of the day, the vast majority remain good guys like Jora, who considers himself ‘well-to-do, an honourable and respectable man’; he drives cautiously and has saved up enough to buy a Hyundai Accent back home.

In another case, riding with a south Indian crew, Ubhaykar learns that ‘neither of them is intent on remaining a truck driver. Their ambition is to become bus drivers in the government-run Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation, a job with a regular salary and benefits, and a modicum of respect.’ One of the author’s skills is to draw vivid pencil sketches of his travel companions—a geriatric-looking school dropout has learnt English by reading roadside signboards, but when he shows his driver’s license, Ubhaykar does a double take as he compares it to his face: ‘Years of accumulated grime have funnelled into the dendritic crevices of his face. Sleep deprivation and exhaustion are a looming presence. Rao is in his late forties but appears to be a senior citizen.’

And like a Columbus finding his America by mistake, Ubhaykar who set out to document life on India’s highways instead encounters a highly multifaceted land full of unexpected phenomena. For example, one driver took up trucking because of his love for music—he enjoys spending hours on the road listening to favourite tunes, knows Kishore Kumar’s Jeevan ke safar mein rahi by heart and renders it well too. Or, observations of Nagaland’s wayside butchers that prompts the author to note that dogs ‘can fool everyone else with those puppy eyes, but not the indiscriminating Nagas, an enlightened people who’ve realized that the only thing one achieves by adhering to food taboos is limiting one’s own sources of nutrition.’

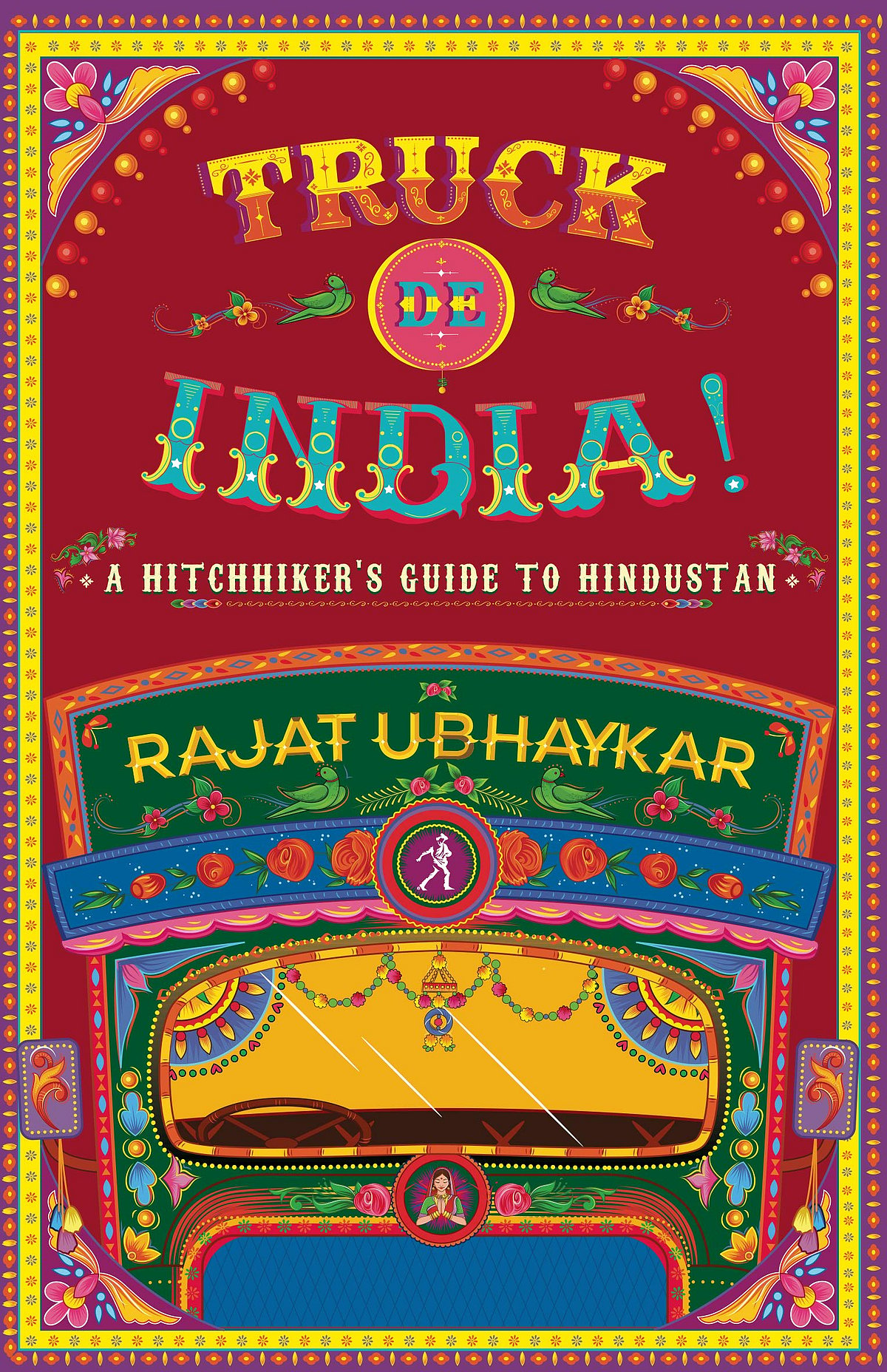

Or, for that matter, the creative world of truck art, ‘a carryover from the tradition of decorating beasts of burden practices by the ancient trading communities of India’. To learn more, he visits a workshop that specialises in painting vehicles and upholstering their cockpits into something in-between Mughal royal thrones and miniature discos with a touch of temple or mosque thrown in depending on the driver’s persuasion. At the end of the long road, when he’s about to get off the last truck near Kanyakumari, he queries the driver as to what’s next, and the reply is, ‘I’ll unload the truck, prepare some food for myself, eat it and go to sleep.’ Ubhaykar tries to hand over a couple of hundred rupees—many pick up passengers to make a little extra—but the trucker refuses with an impish grin, ‘You haven’t exactly been sitting on my head all this while, have you?’

So this is where he finally sits down on solid ground, to think, at the Gandhi memorial at the tip of the Indian subcontinent. At this point, one feels, like the author himself, more enlightened about the physical condition and functioning of the larger world and perhaps even mentally healthier—one might compare the experience with, say, reading Hunter S Thompson’s Hells Angels which is an obviously far more violent trip taken with the dreaded motorcycle gang, or perhaps, more sensibly, Vikram Seth’s From Heaven Lake which is way more lyrical and light-footed, as its philosophising author, then a young student of Chinese, traverses Tibet to get home to India on an ancient overland route. I’d say Truck de India stands its ground among such important travel narratives.

Ubhaykar himself now realises how it ‘was never about the destination, which was nothing but a chance geographical endpoint. It was about meeting people and seeing places along the way. It was about discovering India—its generosity, its desperation, its hospitality, obstinacy, and most importantly, the hope it carries within its bosom…’ He jots down in his travel diary, ‘while my journey is about to end, theirs is a lonely caravan that never halts… India must go on.’