Jhumpa Lahiri: The Author of Anywhere

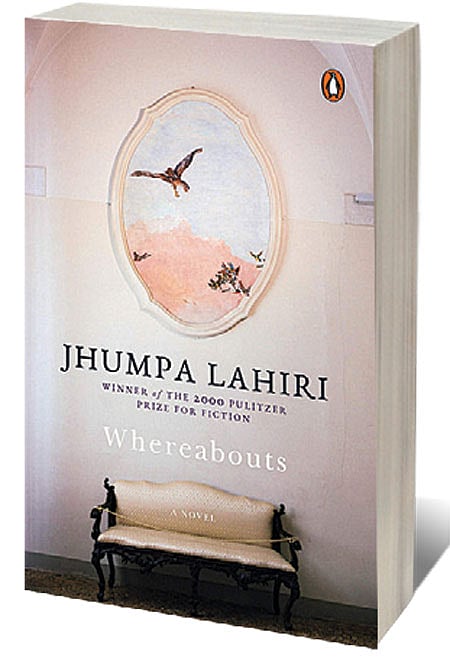

WITH WHEREABOUTS (Hamish Hamilton; 176 pages; Rs 499) Jhumpa Lahiri proves her complete mastery over writing (and translating) in a new language. Originally written in Italian in 2018 as Dove Mi Trovo this is Lahiri’s third novel (after The Namesake, 2003 and The Lowland, 2013), and the first novel that she has translated herself from Italian to English. It is a novel tailored for today, parsed down to the minimum, devoid of excess and allergic to fluff. Lahiri’s previous Italian books In Other Words (2016, translated by Ann Goldstein) and The Clothing of Books (2017) revealed to readers her intention; ‘writing in another language’ represented ‘an act of demolition, a new beginning.’ In Whereabouts Lahiri has not only demolished her oeuvre, she has resurrected it.

Writing is an act of control. To write in a particular language is to make it heed one’s thoughts, it is to weld every sentence to one’s commands. To write in a new language is to relinquish all authority, to start from scratch, to move from a place of abundance to penury. When an author writes in a new language badly, it might seem an act of hubris. When an author does it well, it seems the bravest act of a writer. Whereabouts is not just a brave exercise, it shows that Lahiri truly inhabits Italian. It is no longer an unrequited love affair, it is a fulfilled relationship.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Lahiri has studied Italian for nearly 30 years. Her immersion started in 1994 when she bought a pocket Italian dictionary with English definitions for a trip to Florence. Her relationship with Italian evolves from desire to devotion to obsession to unrequited love. Living in New York, she goes through a series of tutors, births a daughter, births a novel. She decides to move to Rome with her family. In preparation, she stops reading anything in English. She writes in English. But reads only in Italian. In 2011, when she moves there with her family she starts writing Italian, it feels like she’s writing with her ‘left hand’, her ‘weak hand’, it seems a ‘transgression’, ‘a rebellion’, ‘an act of stupidity’, she explains In Other Words. Italian becomes her ‘newborn’, and English her ‘hairy, smelly teenager’. But over time and with nurturing, the second born strengthens, stands on its own two feet and becomes a force to reckon with.

Her previous novels unspooled the lives of an entire troupe of actors, and arched over different places and decades. Her themes remain unchanged, identity, alienation and belonging. But while her previous novels could feel like cinematic reels (who can ever think of The Namesake and not picture Tabu and Irrfan Khan as Ashima and Ashoke?), Whereabouts feels akin to observing a protagonist in a chiaroscuro painting. It catches a single woman in a frame in different shades of light, dark and shadow.

Whereabouts tells the story of an unnamed woman narrator in an unnamed city (one which evokes Rome). We watch her in different places, both real and abstract, and at different times, as the chapter headings reveal, ‘In the Bookstore’, ‘In my Head’, ‘In August’ etcetera. No plot drives this novel, instead told in the first-person it meditates on questions of loneliness and solitude, change and status quo. At a time of chaos, I found solace in this novel for the precision of its language and the abstraction of the content. It makes no great demands on you as a reader; it doesn’t sweep you into Naxalism (The Lowland) or crush you under a train (The Namesake). The life of the narrator of Whereabouts is not riven by worldly strife or operatic family drama. Ashoke after all has lived ‘three lives by thirty’ and was nearly killed at 22. Unlike her previous novels, it doesn’t move from India to the US and back again.

The action in Whereabouts roils the interiors much more than the exterior. It is a Mrs Dalloway for modern times. The novel does not run the course of just a day but like Virginia Woolf’s masterpiece it reminds us that ordinary/everyday lives can be epic lives. Our 45-year-old unnamed teacher has never left ‘this’ city, she enjoys her ‘urban cocoon’, she bemoans the closing of her favourite stationery shop, her greatest joy is writing a sentence or two with a sun-kissed pen. While many of her familial relationships have disappointed (her mother especially, and an ex-boyfriend who was two-timing for five years), she finds comfort in the unexpected kindness of strangers. ‘I board the train, dumbfounded, feeling mysteriously protected by the universe, or at least by that man who gave me something to eat and drink without insisting that I pay.’

Re-reading In Other Words one notices the seeds of Whereabouts sprout. Lahiri’s most autobiographical book tells of belonging, not belonging, and finding a home in a new language. It also hints at how in a new language, Lahiri becomes a new writer. Towards the end of In Other Words, she writes, ‘I continue as a writer, to see the truth, but I don’t give the same weight to factual truth. In Italian I’m moving towards abstraction. The places are undefined, the characters so far are nameless, without a particular cultural identity. The result, I think, is writing that is freed in certain ways from the concrete world. I construct a less specific setting.’ The narrator in Whereabouts similarly adds, in the penultimate chapter, ‘Nowhere’, ‘When all is said and done the setting doesn’t matter: the space, the walls, the light.’

At writing courses one is often told the ‘more specific we are, the more universal something can become. Life is in the details.’ Lahiri’s previous works are the best example of thick descriptions. We can see trays stacked in the fridge of Gogol’s 14th birthday celebrated in 1982; the lamb curry laden with potatoes, luchis, thick channa dal speckled with raisins, and sandesh. We see Ashima walking in Boston, down Massachusetts Avenue and then to Harvard Square, where she delights in a pistachio ice cream. After a trip to India, they return to the US and pack the cupboards with all American produce; Skippy, Hood, Bumble Bee and Land O’Lakes.

The absence of proper nouns in Whereabouts sets it free from geographies and borders. The novel certainly has a European feel to it, but the protagonist could be an Italian or Indian or American woman. The fact that the reader cannot pinpoint her identity is testament to the author’s skills. Lahiri creates a character who we want to dally with, but does not burden her with markers of identity. We take an interest in her, perhaps even identify with her, simply for who she is, and not because of where she is from. Isn’t that the highest purpose of literature, to create empathy for all humans?

While writing The Namesake, Lahiri might or might not have known that nearly two decades later she would write a book without names. But as a reader, one can glimpse this desire to be liberated from the yoke of markers. Gogol (Nikhil) finds himself one day with a couple who are trying to decide the name of their yet-to-arrive child. He announces at the table, ‘There is no such thing [as a perfect name].’ As the conversation at the table continues without him he recalls reading an English translation of something French, ‘in which the main characters were simply referred to, for hundreds of pages, as He and She’. He devoured the book in a few hours, ‘oddly relieved that the names of the characters were never revealed.’

Reading Whereabouts I feel a similar relief. Here is a character I can befriend without knowing her name or nationality. She teaches at a college, walks the city, and we experience its terrain and people through her eyes. We sense that she has been in the same place forever, as she has watched and encountered the same people over years. Her friend’s daughter sees her as a ‘strong, independent woman’ and while she is all of that she will never seize that title. She has never been married, but ‘like all women’ has had her ‘share of married men’.

Solitude hums beneath the story like a vein. The narrator says, ‘Solitude: it’s become my trade. As it requires a certain discipline, it’s a condition I try to perfect. And yet it plagues me, it weighs on me in spite of my knowing it so well.’ It offers her ‘small pleasures’, control of her own space and time.

She sits at a playground on a warm Saturday surrounded by the babble of others and doesn’t feel ‘even slightly alone’.

As an only child with an overbearing mother, and a father who died suddenly when she was 15, she is accustomed to time on her own. She finds the company of others pleasurable, but she doesn’t see the absence of a companion as a ‘lack’. Only on one occasion does she say, ‘There’s no escape from the shadows that mount inexorably, in this darkening season. Nor can we escape the shadows our families cast. That said, there are times I miss the pleasant shade a companion might provide.’

In some ways the woman of Whereabouts is like Ashima even though their contexts differ. In The Namesake Ashima physically moved from Calcutta to Boston, and even though the woman in Whereabouts has been tethered to the same city, she knows alienation, she says, ‘I’ve never stayed still. I’ve always been moving, that’s all I’ve ever been doing. Always either to get somewhere or to come back.’ She echoes Ashima’s sentiments that being an outsider is a ‘lifelong pregnancy—a perpetual wait, a constant burden, a continuous feeling out of sorts.’ While Lahiri’s previous work often unpacked what migration means at an emotional level, in Whereabouts we realise that we are all outsiders, irrespective of whether we stay in one place or move countries. The protagonist of Whereabouts resembles Ashima’s children—Sonia and Gogol, who have been born as ‘vagabonds’. In the 21st century, as millions move between cities and countries, aren’t we all wayfarers, after all?

Whereabouts reminds us that at the end of it all, we are all the same, at the same time, we are all ‘leaving and also staying’. We have all embarked on epic journeys of our own, we are all constantly in motion, and ultimately we are all living intricate lives at any time and anywhere.