Jerry Pinto: Mumbai on His Mind

I RECEIVED A PHOTOGRAPH at the end of my conversation with author Jerry Pinto. The photograph is of a man walking down a Mumbai street clutching an iguana, wrapped in a red towel. The man’s hold on the creature is gentle yet firm. Man and Lizard both have a wistful expression, both stare in opposite directions, beyond the frame. Are both, perhaps, thinking of escape, a way out? The photograph captures an unusual moment in an everyday setting, it is at once ridiculous and humane. It also tells us about Pinto’s writing. The author of numerous books—spanning poetry to cinema to biography—he has an eye for the absurd and a heart warmed by the unusual. To read his novels is to go Haha and Aww on the same page, as one is entertained and moved all at once.

In 2012, he published his first novel, Em and the Big Hoom. Salman Rushdie called this semi-autobiographical work “one of the very best books to come out of India in a long, long time.” A decade later it remains deserving of that accolade as it is that rare Indian English novel that is linguistically daring and deeply moving. It tells the story of an unnamed narrator living with his mother’s mental illness described as “microweathers”. It deals with the darkest of subjects, a mother’s suicidal tendencies, with the lightest of touches. It is the story of a particular Goan Christian family of Mumbai, four Pintos, but it is also the story of all families who are “somewhat love-battered, still standing.”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

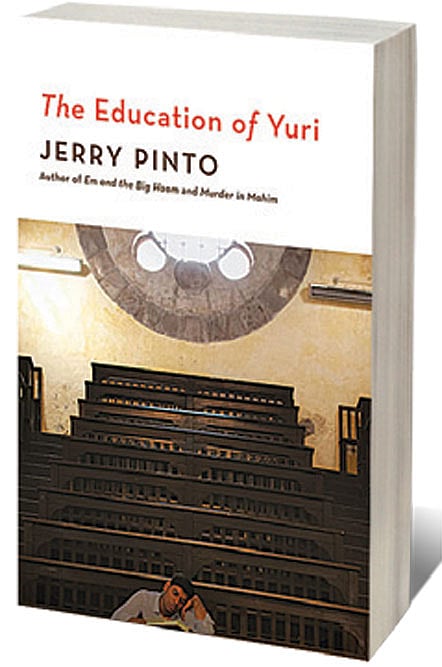

Pinto’s new novel The Education of Yuri (Speaking Tiger; 408 pages; ₹599) doesn’t haunt and linger like Em and the Big Hoom, it is not a book for all time, but it too provides a deep-dive experience. It immerses the reader into the college world of the ’80s, Indira Gandhi has been assassinated, mill strikes are brewing, college students are catching trains and leaving cities to become Naxals. Yuri Fonseca, the protagonist, is the “Padri ka bachcha,” who is not even a priest’s son. Instead Tio Julio, his guardian, his uncle, belongs to the Order of Lay Contemplatives, “an international order of people who had decided to live God-steeped lives”. Yuri stumbles his way through friendships and relationships, he knows not who he is nor his place in the world. He is the nerd, who enjoys taking exams and gives tuitions to make ends meet. What he lacks in courage, he makes up with self-awareness, writing in his journal, “I’m weird. I’ll always be weird. I wish I weren’t needy. I wish I were someone else.”

The Education of Yuri, as the title suggests, follows the lives of the protagonists only through college. Bildungsroman would be the literary criticism term to describe it. But that is too posh a descriptor for a book (and character) that is acutely aware of how words (and accents) create hierarchies. Yuri is marked out as different from the students around him as English is the language that comes naturally to him because it was the language in which Tio Julio thought and spoke, whereas the corridors of the college sparkle with Hindi, Marathi and Konkani. Faced with existential and actual loss, Yuri finds his refuge in English literature, “gobbling up the darkness of Dostoevsky and the puppeteering of Tolstoy”.

Pinto skilfully builds Yuri’s connections and misconnections with his friends and girl friends, but it is the relationship between Yuri and his uncle that truly anchors the book. Tio Julio is that uncommon guardian who treats his ward with love and respect. Yuri even confesses his sexcapades to his god-fearing uncle, only to realise “nothing shocks the truly religious,” and that it is “difficult to mount a revolution against the civilised”.

When Pinto—poet, novelist, short story writer, translator—and I talk, he is waiting to “exhale”. The early reviews are just trickling in and he is unsure about the book’s reception. What he is sure about is his “shit metre that Papa Hemingway talks about”. An avid reader, who consumes a book a day—unless it is Ludwig Wittgenstein then it is more like “21 days to read three pages,”—he can tell the prose from the purple. Even on days when his writing is full of pretence, he will plough through it, because the chaff can be expelled during the edit. He says, “Writing is that kind of game, between what you want to say and what you would like people to hear you say.” Having been in the business of writing and editing for over four decades, he now finds that he exhales a little quicker and easier, because he “trusts that shit metre a lot”.

Speaking from his muse and home, fifty-six-year-old Pinto says he wrote The Education of Yuri not to celebrate his own days at Elphinstone College, Mumbai, but to chronicle the upheavals of that time. He says, “One of the things about growing up is that it is painful. It’s really painful. And in our nostalgia for youth, we forget the pain, we forget how much we were hurt and how much we hurt other people also. So, writing The Education of Yuri was about going back. It wasn’t about celebrating my youth in Bombay or celebrating the city at all. It was more about remembering what it was like to be so young and so confused.”

Pinto joined college as a callow 14-year-old who considered himself “bee’s knees”. (Unfamiliar with that slang, I look it up. It means ‘highly admired person’.) A precocious reader, he had already gone through Robert Ludlum, Jack Higgins and Alistair MacLean while at school. But on his first day in college he encountered two students discussing not only Homer, but also specific translations of the “blind poet” (the only trivia the young quizzer Pinto knew about him). He quickly realised just how much catching up he needed to do. College is always the crucible where the confidence of a schoolboy (or girl) crumbles. Looking back, he says, “This was challenging and wonderful and joyous and what not. It was also extremely humiliating.”

The strength of The Education of Yuri is that it unpacks the humiliations and disappointments of youth. Yuri wants to believe in the revolution, but he is not sure he is a rebel. He wants to believe in self-will, but he doesn’t know if he is an agent or a pawn. He wants to believe in love, but he doesn’t find the spark. Pinto writes about Yuri, “And he didn’t know whether he was with Bhavna because he loved her. He couldn’t be sure what love felt like. Sex with her was like a Parle Glucose biscuit now; he was always surprised at how good it was when he was having it but he did not yearn for it.”

Pinto like Yuri was “naadaan” (innocent) in college. Shackled to his books he wasn’t tuned into the revolutionary thrum of the moment. His was a life of intellectual rigour and not sloganeering. He revelled in borrowing a book from the library only to find that it had last been borrowed in 1922. He spent his days watching plays at Max Muller Bhawan or Alliance Francaise and feeling that his “soul was being uplifted”. Pinto interviewed people and read books that opened the curtains on Yuri’s college experience. With the bulwark of research and not lived experience, he writes of students visiting mill workers in their chawls and raising funds at Churchgate Station. He recounts a time when urban college students jumped onto trains heading to Chandrapur.

Pinto has taught journalism at SCM Sophia for more than 25 years. I can’t help but wonder what it is to write about students of the Emergency while teaching Gen Z. Looking back at his own college days, Pinto remembers a bleakness hanging over prospects. No one knew if they would get employed, and time was spent lying about and reading. He calls his students today karmayogis, who can pretty much do anything they set their mind to. He adds, “I have never met a generation so willing to talk and so reluctant to write. Actual self-expression seems to be getting more and more difficult while self-analysis is getting sharper and more defined.”

OVER THE LAST few years, Pinto has brought out translations, such as Cobalt Blue by Sachin Kundalkar (2013) and a memoir I Want to Destroy Myself by Malika Amar Shaikh (2016). This facility with language uplifts his English novels too. The Education of Yuri is of course set in the English elite corridors of Elphinstone College, but the voices and vocabulary are varied. When Yuri Fonseca of Mahim befriends Muzammil Merchant of Pedder Road, their languages tell them apart. Pinto identifies a moment in the novel, when Yuri uses the phrase, “Means?” Muzammil immediately latches onto that in harmless fun. But Yuri makes a note to never use that word again.

The Education of Yuri succeeds at being authentic because the dialogue is true to its characters. To give just a single example, Arif, Yuri’s classmate, announces that he is no longer a Colaba boy; “House shift. From Colaba, we went straight to Bandra. But four bedrooms, aalishaan. Hey, you’re in Mahim, na? I got a Bullet, now I can give you lift, no train ka tension.” Pinto who translates from Marathi to English and Hindi to English explains the use of multiple languages in a single sentence, “That’s our relationship with our language, we slither and slide between vocabularies, so efficiently and so carelessly, it is more than code switching. We choose a word at some point, but it’s not just choosing a word. It’s also choosing a meaning.” He admits that he has a lot of fun with language and that he loves that aspect of building character and getting the person’s speech right. “And if the person doesn’t speak right, I think they die. I then have to find another way and try something else.”

As a translator, Pinto is also aware of how some words and contexts resist translations. With Em and the Big Hoom being translated into Hindi and Malayalam, he has to deal with how phrases can get lost in translation. Without malice, and with much merriment, he gives the example of how a Hindi translator converted his sentence, “his ears looked like bacon curled from too much frying” into his ears look like “taley huye suar ka maas,” which, one might say, doesn’t have quite the same effect.

Does he ever think of how his work might be translated, when he is writing, I ask? Pinto replies, “Kazuo Ishiguro once said, ‘If you want to be translated, write in a way that will make it easy for your translator.’ And I thought, Kazuo, are you mad? If I let a reader into the room and I’m writing, I’d lose it. Now I’m going to let the translator into the room!” For Pinto that is an impossible suggestion.

In Pinto’s books, languages slither and slide out of each other, because that is how the streets of Mumbai speak. With each of his books he discovers the city anew. It is the city where he sees stunt men perform acrobatics on the beach, catching and throwing each other on the sand. It is the city where he meets a man carrying an iguana. He asks the man, “Yeh kaun hai?” “MJ.” “Michael Jackson?” asks Pinto. “Nahi. Mary Jane,” says the man. It is the city where an iguana called Mary Jane is carried in a tender embrace. It is the city where Yuri got an education.