Jamyang Norbu: Memory Keeper

IT WAS AT A SMALL gym in Dharamshala sometime in the early 1990s, when Jamyang Norbu first caught sight of an unusual visitor. The town was then far from the tourist trap it is today, and Norbu, who had been part of a Tibetan guerrilla force in his youth, was beginning to make a name for himself as a writer and thinker in the exiled Tibetan society.

This unusual visitor was an elderly man. He moved slowly, and he carried a rosary in one hand, perhaps having just completed the kora (the circumambulation of a holy site) around the Dalai Lama’s temple. When the young men teased him that day, he responded with a joke of his own. “Okay boys, back to your training. We have to represent Tibet in the Olympic Games,” he said, as he went about his own exercise routine.

It was only later that Norbu learned that this old man was Bhusang, and that he had been a witness—and a participant—in some of the most tumultuous events in modern Tibetan history. He had been part of a large group of Tibetans who had fought the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) during the 1959 Uprising in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa. His group defended the sacred Jokhang temple, before having to flee to India; he was trained by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and parachuted back to join one of the last remaining resistance groups in Tibet. He fought to the last bullet, but was captured and spent about two dehumanising decades in Chinese prisons and laogai labour camps. Now, old and infirm, he had finally made his way into the exiled community in India.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

Norbu’s face lights up with a smile today as he recounts the memory of first interacting with Bhusang. “He was a real feisty guy,” Norbu says, in an online interview from New York. “He was quite sickly for being in prison for so long. And he was a bit confused sometimes. But he was a chap who never felt sorry for himself.”

After their first encounter at the gym, Norbu spent the next few weeks with Bhusang in the latter’s one-room apartment, listening to the old man recount the story of his life and its struggles, and his many losses, including those of his two children who starved to death.

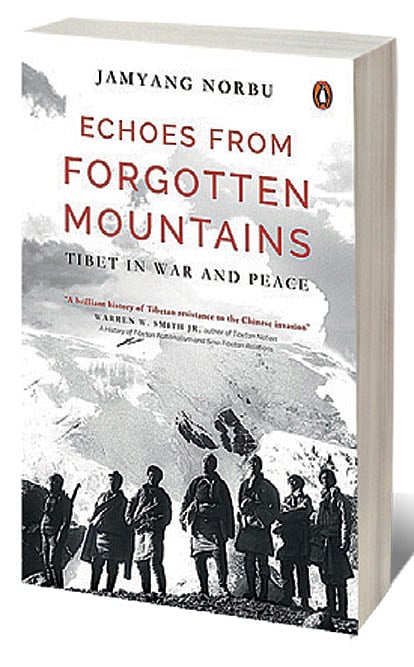

Bhusung’s is one of the many accounts that makes its way today into Norbu’s vast new book, Echoes from Forgotten Mountains: Tibet in War and Peace (Viking; 962 pages; ₹1,299) on modern Tibet and the resistance movement. A handful of accounts have been written on this subject, but few, if any, have attempted something this big and ambitious. Norbu tells the story of modern Tibet, relying upon his many decades of interviews and interactions with primary eyewitnesses and participants, his wide scholarship on the subject, and he does all of this employing a unique framework—that of the memoir. “I did a bit of Tarantino,” he jokes. “Even the timeline goes back and forth. It is a historical work, so I can’t avoid giving dates. But I tried to make it a narrative.”

While he uses the story of his life as a framework, the throbbing heart of the book is the stories of the people in this period, many of whom have been forgotten or their roles underplayed. He looks at old events with fresh eyes. He shows for instance that the Dalai Lama’s escape to India may not have been spontaneous and driven by romanticised notions of warnings by oracles, but in fact was meticulously planned by state officials like the Lord Chamberlain Phala Thupten. He brings to life now-vanished facets like the songs that were sung in Lhasa, the neighbourhoods of the capital and frontier towns in India and China that were trading with the country. It is a work of stellar scholarship, but unlike most academic works, it is also a touching portrait of a place and a time, and its participants, by someone who cares deeply.

NORBU BEGAN TO first think of a book of this nature sometime during the turn of the last century. He had just completed The Mandala of Sherlock Holmes (1999) where he uses Arthur Conan Doyle’s explanation about how the sleuth had travelled to Lhasa after initially being killed off by its author, to spin a fabulous yarn about the detective’s adventures in Tibet. He was looking for a publisher, when Liz Calder, the then founder director of Bloomsbury asked him to meet her. Calder didn’t want to publish The Mandala of Sherlock Holmes, but she wanted him to do a book on Tibet. “She didn’t like the stuff that was coming out [about Tibet]. All this feel-good stuff about Tibet. Even injis [Westerners] writing about beautiful Tibetans, about the Dalai Lama and stuff,” Norbu says.

By then, Norbu was already getting recognised as one of the sharpest minds on Tibet, although he was also attracting notoriety in Dharamsala for his criticism of the exile leadership. “Liz said, ‘I don’t want an introduction [in the book] from the Dalai Lama,’” Norbu recounts, “I told her, ‘I won’t get it even if I tried.’”

When he began the project, Norbu was conscious that there had been many books on modern Tibetan history. “A lot of historical writing on Tibet is by anthropologists who took on Tibet studies. So, the writing to an extent is stilted.”

He estimates he spent about 14 years writing the book. The work put into it however dates back even further. He had been conducting interviews and collecting records as far back as the 1970s and 1980s. “I’d interview anyone I found interesting. I was thinking of it [a book], but I hadn’t worked it out. I would use some of them in other ways. I wrote plays [for instance], children’s stories, a lot of which I did not publish. I still have tons of interviews I had done,” he says.

The book’s size however kept getting larger, and Bloomsbury unsurprisingly baulked. Norbu however declined to trim it down, not out of a sense of vanity, he says, but because he was convinced the story of the resistance movement had to be told in its full scope. He was preparing to self-publish, when Penguin Random House India stepped in.

The framework of the personal narrative was of course eminently suitable to this book. Norbu knew many of the principal characters intimately. He had joined the CIA-funded Tibetan guerrilla force in Nepal’s Mustang region, become friends with many of the fighters and agents, and knew individuals like the Lord Chamberlain Phala closely. “The whole trick now for me was to not bog it down as a history lesson.”

NORBU WAS, OF COURSE, not always intimately involved with the Tibetan movement. Although he was born into a prominent Tibetan family in Darjeeling, some of whose close relatives had played important roles in Tibetan history, in the 1950s when Tibetans began to pour into these towns, he was just a young bookish boy. “I knew what was going on in Tibet. We had all heard stories. But it hadn’t impacted me as a person,” he says.

This changed when he began reading Ernest Hemingway, especially the novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. “Suddenly it all clicked,” he says, smiling. “[General Francisco] Franco and the fascist army, that was the PLA. The Spanish guerrillas in the mountains, they were the resistance fighters in Mustang.” Norbu had only just completed his schooling, and now with the romantic figure of a Hemingway character as his model, he rebelled against his father, left home, and tried joining the guerrilla camp, which was operating in the remote area of Mustang in Nepal, only to be turned down by Gyalo Thondup, the Dalai Lama’s brother who was managing the resistance movement then from Darjeeling. “He was nice about it. But really they didn’t want kids up there,” he says.

Norbu spent his time then in various Tibetan settlements that were being built in India. He recounts heartbreaking moments around this period in his book. He writes of dormitories in Dharamshala, where every morning, one or two children, traumatised by the war and exhausted by the journey, would be found dead in their beds; of watching, through grimy bus windows, a thin column of smoke always rising from the burning pyres.

When Norbu was finally able to join the fighters in Mustang, the then 19-year-old found the place nothing like he had imagined. “I thought we would have to live in tents. But the Khampas [Tibetans from the eastern province of Kham, who made up most of the guerrilla fighters] were really good architects. They had made buildings, and even lhakhangs and gompas [temples and monasteries], and built bridges on the trail up to Mustang.”

Mustang and his experience with the fighters, he says, transformed him as an individual. “The Khampas are very different from the Tibetans you see in exile [many of whom come from central Tibet and embody the self-effacing qualities from the region]. Khampas are bigger physically and they have a tremendous sense of themselves. I found them very admirable. And if you look at it, these were people stationed in the end of nowhere, in a place like Mustang, taking on the world’s largest army, and not fazed by it,” he says.

Norbu had prepared for his new life as a resistance fighter in the way a studious recruit might. He had a mule carry two boxes of books on military history on the journey with him. “I thought if you are going to really fight, you need to know about war,” he says.

He may have gone to the camp to become a guerrilla fighter, but up in its cold and inhospitable environment, he found the ideal conditions for reading and contemplation. The resistance published a magazine for its members, and Norbu began to write for it. There was also a school at the camp, and he began teaching the fighters English and Nepali, and arithmetic and simple accounting, so some of them could help in the resistance’s clerical and administrative needs.

The Americans were beginning to make its first approach to China during this period, and a withdrawal of support to the resistance seemed imminent. “I realised this won’t last forever, and we needed to think of other ways to keep up the struggle,” Norbu says. He realised he could do this through writing. But for it to have any impact, simply reading widely wasn’t going to be sufficient. He began keeping a journal. He would cut out pieces of paper where he would jot down every new word, he encountered, so he could check them out in a dictionary at the end of the day.

Once it became clear that the US was withdrawing support, the members began to approach other governments. One of the intelligence services interested, not in supporting the camp entirely, but by paying agreed-upon sums at regular intervals for intelligence reports on Tibet and China, was the French, who took Norbu to Paris to train him in intelligence gathering. Norbu was back in Dharamshala recruiting young members for this new intelligence operation, when he learnt that the camp was being shut down. “It was a big blow,” he says.

Nepal had gathered forces to close the camp, and while the Tibetan fighters were confident of fighting it out, a representative of the Dalai Lama travelled to Mustang carrying a tape-recorded message of the Dalai Lama asking them to surrender. Finding themselves unable to refuse the Dalai Lama, many members put down their arms, some even died by suicide; while one group refused to surrender and were later ambushed by Nepali forces. “It was done in too much haste. The Khampas could have held out much longer and could have negotiated something with Nepal,” Norbu says. “Dharamshala, especially His Holiness and some of his immediate advisors around him, always hoped for some rapprochement with China. Mustang was a bit of an obstacle for them,” he says.

IN HIS INTRODUCTION to Echoes from Forgotten Mountains, Norbu quotes the famous Milan Kundera line; “the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting”. He uses it in the context of the Chinese state’s repressive measures to erase the memory of an independent Tibet and the fight put up by Tibetans to counter it. But it could also be extended to the exile government’s attempts at underplaying the history of the resistance movement and its attempt to seek autonomy within Chinese control.

Norbu remains fiercely critical of this approach. When he returned to Dharamsala, he worked with several publications and journals, some of which he founded and edited. His writings, where he criticised the exile leadership and took on Western academics who toed the Communist line, began to win him large audiences. But it also brought along trouble. He was branded as being “anti-Dalai Lama,” and there were occasions where groups of people assaulted him. He also received death threats. “I don’t blame people for believing that China was changing [in the 1980s and 1990s]. The Chinese leadership is very good at giving appearances. They are very good at propaganda. But the Tibetan world and His Holiness got pretty offended with me. I was disturbing their newfound relationship with China,” he says.

The exile community is currently gripped with the fear of what the future holds for them and the movement after the current Dalai Lama dies. It is now widely believed that China will appoint its own candidate. Although the Dalai Lama has put in place a process by which a new successor could be found, what has kept many anxious are his comments about the validity of such an institution in the current age. Norbu has his mind clear about it. “I don’t believe in reincarnations. But I think it is the need of the hour for the institution to go on,” he says. He believes the next candidate should ideally be from India, from the Tibetan Buddhist communities in Arunachal Pradesh or Ladakh. “This way we can get India into the picture too. They will have to support the candidate if he is from India,” he says.

Norbu lives in New York now, from where he continues to maintain his popular blog on Tibet and where he also established the High Asia Research Centre, a library-cum-research institute on Tibet and other high Asian regions. Whenever he travels to Dharamsala, he puts in a request to meet the Dalai Lama, but like always never gets an audience. He did this once again when he travelled to the town in 2018, but this time he got a call, saying the Dalai Lama wanted to see him.

The audience lasted for about an hour, where the two reminisced about many things. At one point, Norbu writes in his blog, the Dalai Lama told him he wants to talk about the Middle Way Policy (the policy of seeking Tibetan autonomy within Chinese control) and how several world leaders supported it. “I don’t want to argue. I just want to explain it to you,” he quotes the Dalai Lama. As the meeting came to an end, and the Dalai Lama handed him some Tibetan pills so he would not become porto (old) before his time, Norbu requested that the Dalai Lama grant his thumon (prayers) for all those who struggle for rangzen (complete independence). “Of course, most certainly, you all need not worry,” he replied.

Towards the end of his book, Norbu recounts his journey to Camp Hale in the Rockies, where Tibetan guerrilla fighters were trained, for a ceremony to put up a commemorative plaque for the fighters. The next day, he drives up the Rockies to a high mountain pass with a friend. He ties a white Tibetan khata scarf to a guardrail and then screams the Tibetan chant “lha gyalo— ki hi hi (victory to the gods).” That cry echoes through this book.