India of the Mind

IN THE ARTHASHASTRA, Kautilya carefully elaborated on the kind of space that is ideal for the location of a kingdom’s capital. He recommended a site “at the confluence of rivers or on the bank of a lake—either a natural pond or a reservoir—that never dries up.” He does not stop there and follows up with an elaborate discussion on the location of forts, their spatial orientation and the minute details of their parts. In a pre-map age, this was the stuff of geostrategy. The dating and composition of the Arthashastra are hotly debated but there is little doubt that it is an ancient treatise. It is also one of the clearest examples that ancient Indians thought carefully about strategy and what passed for international relations in that age.

By the end of the 20th century this image had been neatly reversed. It was, to give one example, argued that, “Because India has lacked political unity throughout most of its history, Indians have not thought in terms of national defence planning.” Such claims easily cross from the strategic realm to the metaphysical one: “The Hindu concept of time, or the rather lack of a sense of time—Indians view life as an eternal present, with neither history nor future—discourages planning.” (Both quotes are from George K Tanham’s Indian Strategic Thought: An Interpretive Essay).

Certain scholars bristle at such claims by pointing to the Arthashastra (or lately, to Kamandaki’s Nitisara, another ancient treatise) but are unable to explain what happened to Indian strategic thought in the huge chasm of time that separates Arthashastra and modern claims. While resentment is one thing, scholarship is an entirely different matter. The two are not substitutes for each other.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

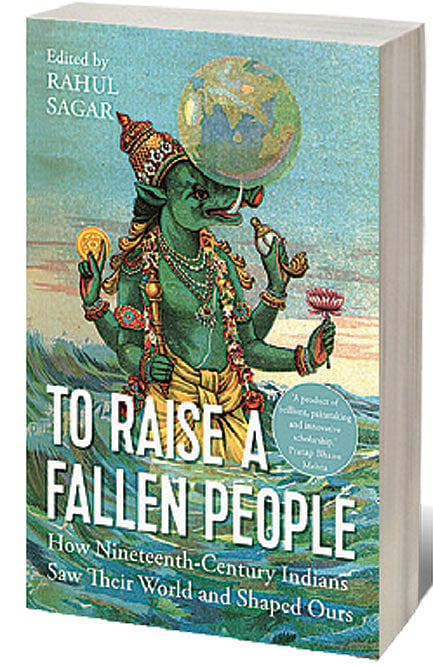

All this is changing. In his new book, To Raise A Fallen People: How Nineteenth-Century Indians Saw Their World And Shaped Ours (Juggernaut; 312 pages; ₹ 799) Rahul Sagar, a scholar of international relations, casts a different light on the history of Indian strategic thought. Far from being a British bequest that was only developed after Independence, Sagar has collected a vast trove of newspaper articles, pamphlets and other materials from the 19th century on a large array of subjects dealing with how Indians saw the world. What emerges is a very different picture. From the Great Game to the Eastern Question, Indians actively opined on what was best for their nation-in-the-making.

Take the Great Game, for example. In literature (Rudyard Kipling’s Kim is an example) as in the real world, the competition between Russia and Britain was the subject of “high politics” in which the “wogs” had no role to play. The result of this received wisdom is that key debates conducted in the Indian press have been overshadowed in scholarly literature. There is, to be sure, a passing reference here and there but the picture is one of British soldiers and diplomats trying to contain the “Russian menace”. It is well known that the debate on how best to check the Russians—whether by recruiting more Indians to the army or by restructuring expenditures in a systematic manner—was part of Indian nationalist awakening. The names of Dadabhai Naoroji and Gopal Krishna Gokhale are associated with the debate on “wasteful military expenditures”. Less known are pieces of the kind that appeared in the Oriental Miscellany, a Calcutta periodical, that analysed British strategy that veered from “masterly inactivity” to the disastrous “forward policy” in Afghanistan. Signed simply as “India”, the piece appeared in the Oriental Miscellany in 1879 and is remarkable for its clear-sighted analysis of British strategy on Russia. Pieces by “India” and many others included in the book throw a very different light on the sources of Indian thinking on strategic matters.

The author has collected writings on topics ranging from racism to foreign travel and from free trade to learning from the west. On the surface they all seem to be subjects that are concerned with domestic issues. But a close reading shows that they were potent sources of how Indians viewed the world they lived in. Had India been independent in that age, these would have been material for understanding the domestic sources of foreign conduct.

Sagar’s analytical question is simple: “The ideals of the recent past cannot explain the pragmatism of the present day; the ideals of the distant past cannot explain the half-heartedness of the present day.” How does one explain the gulf between the ruthlessness of Mauyran statecraft and modern Indian pacifism (mistakenly described as “non-alignment” by its practitioners)? In Sagar’s reckoning, there is no straight line that links the two. There cannot be for Indian history is made of a vast deposit of layers each with its own peculiarities and outlook. His starting point to understand the past is to look at the 19th century, for that is when India’s modern intellectual history—the source of its ideas—begins. The echoes of those ideas can be heard right until the present day.

This is treacherous terrain to move on. There is, to begin with, a practical problem: getting hold of the materials set down in the 19th century is not easy. They are scattered around the world. What has been gathered in the book required time, money and an army of people helping each other. This is not easy, as one goes deeper in time.

The bigger obstacle is ideological. Take for example, the following passage from the introductory essay in the book. “Here it is necessary to clarify that this overview does not claim that nineteenth-century discussions on international politics directly explain contemporary Indian foreign policy decisions. Such influence is certainly possible. The great figures of that era are still read and cited as inspirations by decision-makers today. But it would require a very different kind of volume to flesh out such a claim.” Then again: “The conjecture this volume offers is that when we stand back from explanations about why a particular decision was made, and ask why the decision was considered a good idea, the trail of answers is likely to lead to an idea originating in nineteenth-century India.” (Emphasis in original in both quotes).

To put it mildly, the author of a pioneering work is being overly cautious. But there is an explanation for that. The “high politics” of the era was indeed under colonial control but surely there is nothing controversial in the claim that ideas of 19th century Indians influenced the 20th century ones? The trouble is that in Indian and the so-called “South Asian” academia in the West, anything associated with “native” thought remains unacceptable even today. In case the ideas have an ancient provenance, they are plainly taboo. If “Hindu thinking” was allegedly timeless, modern Indian strategic thought owes everything—even in theory—to the British. To give a contemporary example, a book like Ancient Chinese Thought, Modern Chinese Power by Yan Xuetong is impossible to conceive of in an Indian or “South Asian” departmental setting. If the 19th century alone poses such formidable obstacles, one can only imagine the furore a modern commentary or analysis on the Arthashastra is certain to unleash. The British can have a Hobbes, the Italians, a Machiavelli and even the Chinese can proudly claim a Han Feizi or a Xunzi but dare a modern Indian reclaim an ancient thinker of his country? This is the stuff from which intellectual emasculation is made.