Imaginary Homeland

OVER THE SPAN of my twenties, literary criticism became both home and the world for me, a place where I could achieve self-definition while also absorbing other truths, other trades. In particular, literary criticism became a site where I could fuse and further my two great loves among literary forms. The essay, and the novel. I want to say something about each of these.

Of course, the jobbing book-reviewer should take pause before he claims the status of either literary critic or essayist (and I claim both). These are overlapping categories, and the nuances of the differences between them can reveal a great deal about what is at stake in the act of literary response (which after all is something that is going on in the mind of every reader, not just those readers who write about their reading).

Any book review is, by the loosest definition, an essay:

that is, a piece of discursive prose about a certain subject. But book reviews are highly perishable—written in haste to deadlines and tight word counts, published in periodicals which are in a few days carted off by the kabadiwala, and, by virtue of having always to focus on what is newly published, often forced to engage with works that are themselves ephemeral and mediocre. Ideally a good book review is a thoughtful report on a book, supplying evidence to support its claims about the author’s worldview, methods and style, and arriving at a persuasive evaluation, spelled out or implied, of the work in question.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

A book review rises to the status of literary criticism when it shows itself to be historically and technically informed about various literary and moral aspects of the work it addresses and the genre in which it is written. It also qualifies as literary criticism, in the academic sense (which is where, with the professionalisation of literature, the great bulk of literary criticism is today generated) when it shows the rigour of a certain literary-critical method or theory of literature, even if it sometimes thereby recuses itself from the realm of the lay reader, or, just as problematically, jettisons questions of aesthetic value in favour of social or political questions, or subsumes literary creation to theoretical superstructures.

Even higher on this scale, therefore, is the book review or work of literary criticism that aspires to the status—it is the reader who must judge whether it achieves it—of an essay: that is, a distinctive combination of objective and subjective perceptions, written up in an unmistakably individual

voice; possessing and proposing nuances of thought, perception and style that enact the pleasures of thinking and feeling about art; and seeking to recreate the drama of literary engagement in a language that itself incarnates those qualities that make literature the most elevated arena of language. Then a book review can become all of these things: literary criticism, essay, literature.

To me the literary commentary of many writers—some book-reviewers, some not—reaches this level of intensity: VS Pritchett, Alberto Manguel, James Wood, Pico Iyer, Andre Maurois, Pankaj Mishra, William Pritchard, Chaturvedi Badrinath, Shama Futehally, Algis Valiunas, Clive James, Robert Dessaix, Arshia Sattar, Eric Ormsby, Meenakshi Mukherjee, Kenneth Rexroth, Michael Schmidt, DR Nagaraj, Adam Kirsch, Paul Theroux, Mario Vargas Llosa, Milan Kundera and Jorge Luis Borges.

AND NOW TO the novel—my favourite subject of all. (i.e., This will take some time.) The novel is an astonishing literary invention, raised over three centuries to ever-new heights by hundreds of ardent and questing exponents. It is a very capacious, amiable form; it participates in both the quotidian and the ethereal. From my early twenties onwards, I began to feel that, although I loved all kinds of literature, it was novels that had first claim on my allegiance. Individual novels can be highly partial to certain moods and subjects, but the novel in general leans towards large-heartedness, complexity, contrast, self-awareness, scepticism, a dissembling sophistication and a shambling grace. The passions and sentiments of characters are balanced by the commentary and rumination of narrators; scenes of solitude and private life are set in counterpoint to the world of the street and of society; magisterial language and highly polished sentences are combined with naturalistic speech and street slang. Meaning is made at the level of human drama and also by the form in which the story is cast, by who is doing the telling. The novel is also a sophisticated time machine. In a good novel the flow of life, highly contingent and unstable, can be experienced on the page; the experience of time is intensified and all the banal moments and longueurs of real life are ruthlessly weeded out.

Here was life, I thought to myself as I marked up and wrote about a novel every few days, seen in the round with a thrilling—sometimes terrifying—intensity of perception. The flow of artfully constructed verbal pictures in novelistic narration was rapid and vivifying; the precisely tuned sentences quickened the pulse, stung the conscience, created a thirst for experience. The more novels I read, the hungrier I became to read more—to live life, or at least a couple of hours of every day, with the heightened sense of intensity and significance that they conjured up. The sense of reassurance provided by novels was amazing, like that given to a country by a strong central bank. No matter how long one lived, one would never run out of great novels to read.

Even better, novels could provide, for acutely self-conscious souls such as myself, a liberating escape from the self. In novels you could get into the minds of other human beings and stay there until you could see reality as much through their eyes as your own; in effect you became a compound human being, both yourself and someone else. The last page of a novel often felt to me like a devastating farewell from one or all—sometimes you had to really think to work out which one—of the protagonist, narrator, or writer.

And just like in life, reality in novels did not easily give away its secrets. To pierce the veil of reality of novels was to gain confidence in doing the same at some point for life. You had to work out the code of the book, tune your own receptors to the pitch of the writing, piece together the narrator’s worldview from the shards of observation about characters, be alive to the play of irony, the meanings of certain juxtapositions, cuts, and switches of perspective. Novels were written to be read, but novels were themselves readers: they read and interpreted the people within their narrative field, and they also supplied the means to read entire cultures, the lives of distant countries that one might never visit.

The novel, literary history tells us, had its beginnings in the birth of modernity in the west. In societies like India and Egypt, Brazil and Korea, it was a transplant. But what did that matter? The important thing was that wherever the novel went, it merged with that world’s indigenous storytelling traditions and reappeared with a new face and form, a new way of being. It was the literary version of the traveller who makes himself at home anywhere he goes.

And, fired by my position as the chief book reviewer of a newspaper, the more novels I read by Indian writers past and present—Amitav Ghosh and Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Senapati and Nayantara Sahgal, Salma and Yashpal, Anjum Hasan and Vikram Chandra—the more I wanted to persuade every countryman of mine, every reader everywhere in the world who loved novels, to read these writers. Even better, in reading them I was convinced I had chosen the right profession, that there were few instruments so well suited to the depiction and interpretation of Indian life as the novel, that there was a lifetime’s worth of reading and writing, thinking and travelling, for me in this realm alone.

Having been formed by reading novels as much as the contours of my own biography and the conflicts of my psyche, I have in middle age come to see novels also as an unusual kind of wisdom literature, a place where a young person, acutely conscious of callowness and malformation, may be exposed to the nuances of human nature, social life, romantic love, and history, and educated in the subtle workings of cause and effect. And also, the novel can work as a sort of imaginative safe space, where rage, violence, grief, and trauma can be vicariously and cathartically experienced and one’s own psychic wounds healed. I don’t doubt that this was one of the main reasons for my attraction to novels in my youth. A novel can be a refuge for those who are thrown off by life; the action of understanding what is going in a text can serve as a sort of substitute for the challenges of action in the world.

And so I find this double aura of poise and perplexity hanging over all the books of my twenties. I could be very adult and composed on the page. But those who met me after having read me often sensed, I felt, a great disjuncture between writer and person. I could speak in my writing voice with a poise and confidence that was worlds removed from my ability to direct my own selfhood outside of literature: my sense of myself as a young man alienated from his society both by his upbringing in a fractured and frightening home with its doors barred against the world, and then by his marginal status as a drifter and a writer in a society that might set great store by learning but not necessarily by books or novels. In my relationships, I was a prisoner of my own history, diffident and reactive, pliant and conflicted, reconciled to the feeling that I might never escape this burdensome selfhood in this life.

There was another realm, however, in which I might speak my love and spend my passion without the sense of social and psychic barricades. That was literature, and I was enormously grateful to it. I have written essays about diverse writers and subjects, but they are all an expression of that gratitude, of life lived and work done under the sheltering sky of literature. And in fact the fires of art create the means for all manner of transcendence. Writing book reviews and living entirely by literature gave me the time and space, the models and the means, to become a novelist. And becoming a novelist, being able to escape into the imagined worlds of characters I had myself created, gave me the means to remake myself a person.

In retrospect, looking back at my twenties, this explains why it took me much longer to become a novelist than a literary critic. For literary criticism can be composed from a point and station within the field of literature. But novels are made half from life, half from literature.

And I had a lot of ground to make up on one of those fronts.

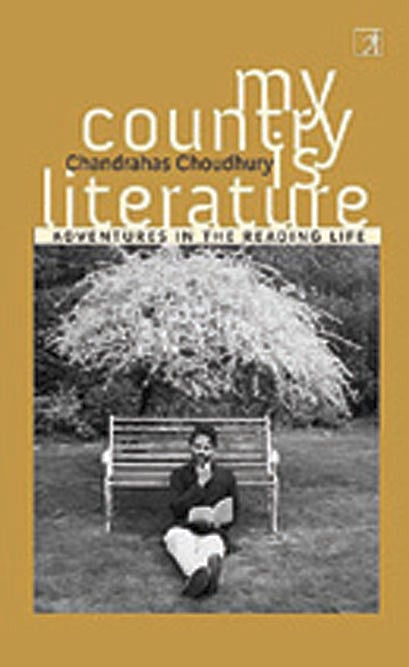

(This is an edited excerpt from My Country Is Literature: Adventures in the Reading Life by Chandrahas Choudhury, releasing on November 30th)