Homeland Reveries

FOR THE 38-YEAR-OLD Tibetan writer Tsering Yangzom Lama, the 2010s began on a momentous note. Working as an activist for the cause of Tibetan refugees, Lama (who was raised in a Nepal refugee camp before immigrating to Canada and then the US) started writing what would become the first draft of her novel We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies. By 2013, she had finished an MFA in Creative Writing at Columbia University, New York, and by the following year she had deleted the first draft of her novel entirely. The narrative was always imbued with history. It centred around the fortunes of three generations of Tibetan women, starting from 1960 (China’s invasion of Tibet) all the way up to 2012. But the tonality changed from light-hearted and comedic to intimate and urgent—an almost mystical voice that connects the trials of the 2010s (the character Dolma’s adventures in white-dominated American academic spaces) to the visceral, heart-wrenching escape attempt in 1960 (Dolma’s mother Lhamo survives the harsh journey by foot to Nepal, but Lhamo’s mother, an ‘oracle’, doesn’t).

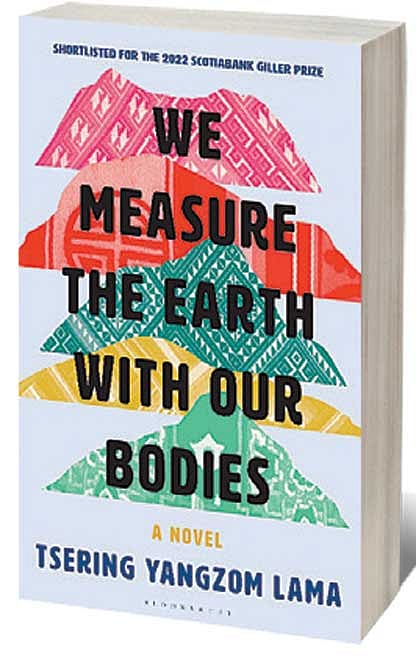

Published in Canada (and the US) in 2022, We Measure the Earth with our Bodies (Bloomsbury; 368 pages; ₹599) was shortlisted for the Giller Prize, one of Canada’s most prestigious literary awards. Ahead of the novel’s India release earlier this month, Lama spoke about the making of her debut book during an online interview. “I spent a lot of time studying the oracular tradition,” Lama says, “in particular how a lot of Tibetan women were oracles in villages, away from the centres of power, as healers, as teachers, as negotiators, as women connected to the land. I was just going where my curiosity led me, to be honest.”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

One of the starting points of the novel was when she came across a small Tibetan mud statue (a ‘mahasiddha’) at the Rubin Museum in New York—and started thinking about how there was virtually no mention of the tumultuous geopolitical conditions that led this artefact, inevitably, from Tibet all the way to the West. In the novel, the fates of the three generations of protagonists are tied up with a statue of “the Nameless Saint,” a statue that is said to vanish and reappear in front of people in their hour of need.

“These really elite spaces, universities and museums and so on, they’re the places that are holding the narratives and the knowledge of Tibet,” Lama says. “But they do so in very particular ways, to serve a Western curiosity and, I guess, a Western lens. In a lot of these spaces there is very little mention of the colonisation of Tibet. It’s almost as if they take the culture and separate it from the people, from the political conditions that led to their suffering. There is no context or acknowledgement around what has to happen for a statue like that to travel from Tibet and end up in an elite institution in New York City.”

The novel uses Dolma’s 2010s academia experiences very effectively, juxtaposing them with scenes set in the past, where her mother is selling trinkets to tourists in Nepal for a living. Slowly and artfully, the novel urges us to see the parallels in both situations; Tibetan culture being ‘consumed’ by third parties who are well-meaning but frequently oblivious to the struggle of the refugees. Remarkably, We Measure the Earth with our Bodies is vigilant to these nuances but never judgmental. Instead, by ping-ponging between the 1960s/70s and the 2010s, Lama shows us how these characters—Lhamo, her sister Tenkyi and her daughter Dolma among them—process generational trauma in very different ways, and what these differences signify for the texture of modern-day Tibetan lives; for a people without a country, so to speak.

“The earlier generation is very much ensconced in the tourism economy, the economy of refugees,” Lama says. “It’s how Tibetan refugees survived at that point in time — selling trinkets to tourists in Nepal and selling sweaters in India. I wanted my book to be granular enough to reflect that life. And yet, there is a certain resonance with the academic spaces we see Dolma entering a generation later. The presence of Tibetan refugees in both cases is contingent…. dependent upon a certain safe, non-threatening, available persona.”

The novel is chock-full of gorgeous, funny-sad passages. Some of my favourite sections involve Dolma’s life in Canada, as she lives with her aunt Tenkyi (now haunted by her past and working as a cleaner) and seeks to become a scholar of Tibetan Studies. This one, for example, tells us how even Dolma’s name is midwifed by her new home and the constraints imposed by “the Canadian tongue”.

“The Canadian tongue struggles with our names, so it gives us new ones. Often it happens during our first moments on this soil, when a border agent scans our strange, laminated documents and speaks our name anew. From that moment on, I was no longer Doh-ma, a short, soft name spoken with the deepest recesses of the throat and ending with the sound we utter from our first breath: ma. Instead, I became Dol-mah, a name that lurches at each syllable and ends as if to ask: ‘Is that really you?’”

Dolma’s bookishness allows Lama to tap into some well-known Western depictions of life in the Himalayas, and then use Dolma’s commentary on these depictions to deliver some decidedly contemporary insights.

For example, Dolma has a conversation with an American man named Horowitz outside her professor’s building, about the 1947 movie Black Narcissus—directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, (often called ‘The Archers’) and based on the Rumer Godden novel of the same name. She is enough of a bookish aesthete to appreciate the technical finesse of the narrative, which follows a group of Anglican nuns living in a Himalayan palace (and former harem) littered with erotic illustrations. But she is also horrified by the brownface-wearing white actors speaking in “this awful tongue of invented grunts”. The passage describing her feelings about the film had me smiling and nodding along.

“Sitting in Henri’s chair, I had felt washed in shame, imagining that this was our image in the West. It all seemed like a horrible misunderstanding—as though someone far away had tossed together a dozen fabricated characteristics from India, Nepal, China, and Tibet, picked randomly across centuries of history, shook them around in a box, and let the pieces fall out. Yet the senselessness of the images flashing before me didn’t even seem to matter for the film, because the locals were only a backdrop.”

The bit about locals being “only a backdrop” assumes greater and greater significance as the novel progresses, of course. And the fact that Black Narcissus is (rightly) seen as one of the high points of post-WWII Western art, is also used to show us something essential—the inherent difference in the way a white person would use the word ‘tradition’, for one.

“It’s really interesting that when we say ‘tradition’ it suggests a psychic connection with beings across centuries that you are not even conscious of,” Lama notes. “And then there’s the fact that the Tibetans buried things under the ground when they fled…so that makes it a very different kind of prayer. It’s not a teaching from a teacher but a prayer about the ability to return, the people’s faith that the land will keep things safe, maintain things for us across decades, centuries, millennia.”

We Measure the Earth with our Bodies is highly recommended, regardless of how much you know (or don’t) about the past and the present of Tibet. This is a nimble, versatile debut from a writer we’re going to see a lot of in the years ahead.