High Stakes

Long before British surveyors realised Peak XV to be the highest in the world and rechristened it Mt Everest as the world knows it today, the mountain had other identities. The Tibetans worshipped it as Chomolungma or Goddess Mother of the World, while on the south side, the Nepalese bowed their heads to Sagarmatha or Goddess of the Sky.

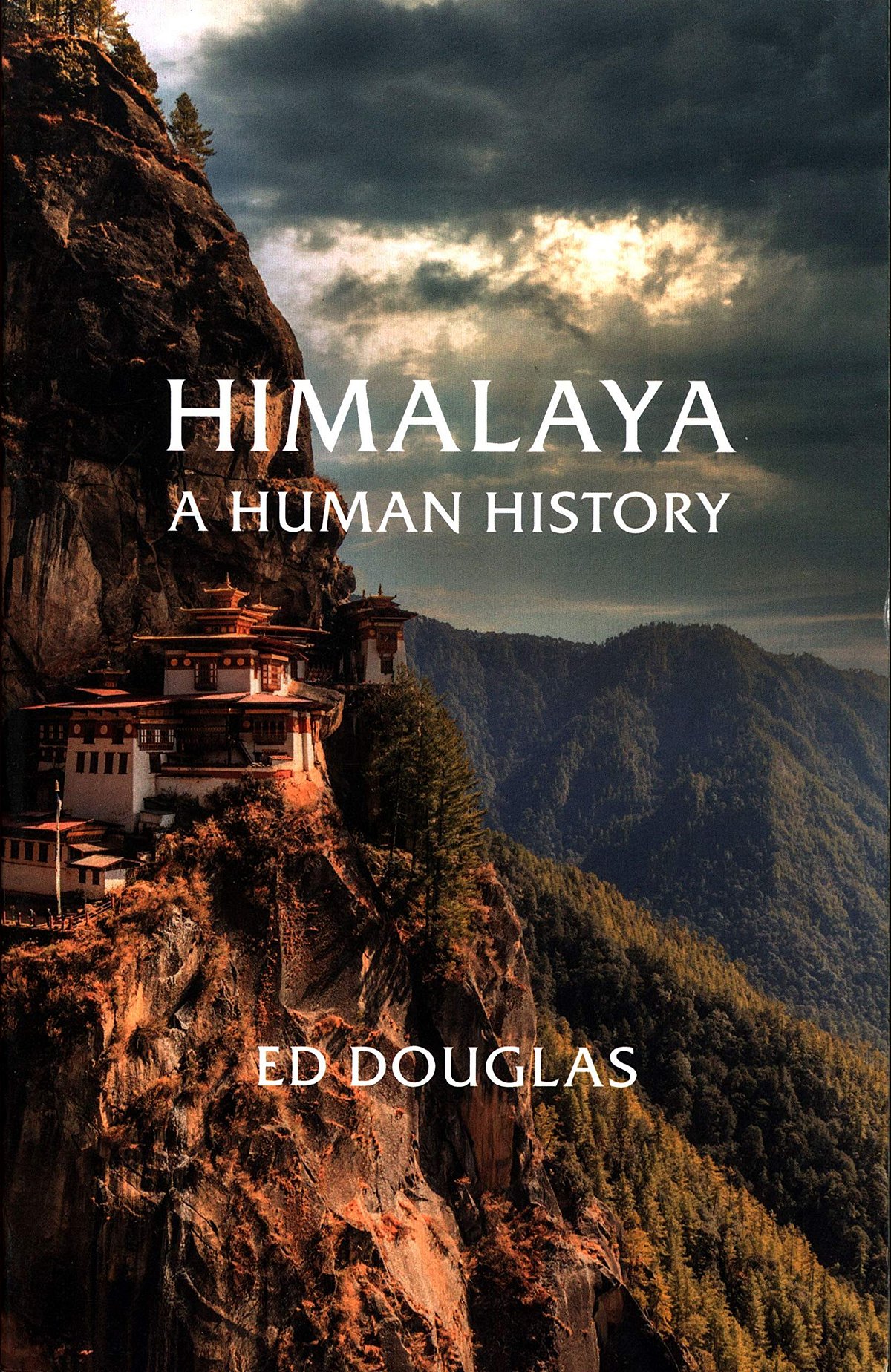

These are communities that have blossomed in the shadow of the Himalayas. And, in turn, have found a sense of belonging in some of the most stunning yet severe landscapes of the world. The rise and fall of these civilisations and how the mighty mountain range has shaped them over the years is what Ed Douglas chronicles in Himalaya: A Human History.

This kingdom of snow continues to intrigue all kinds of outsiders, just like it drew everyone from explorers and botanists to ascetics and pilgrims back in the day. A few itinerants fell for its charms and stayed back; others found a safe refuge in the remote valleys and at those lofty heights.

As civilisations emerged, straddled across the length of the Himalayan belt, the Jesuits arrived as the first visitors, surviving arduous journeys across desolate landscapes. Once the Britishers set base on the Indian subcontinent, they too took note of this blank on the map. While exploration was always at the back of their mind, the bigger picture was to stamp their authority on the region, primarily through trade and dialogue, before taking to more stringent measures.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

This led to the rise of a breed of diplomats who doubled up as explorers and thrived on the raw adventures that these unchartered territories had to offer. Kingdoms rose and fell as a result of the many partnerships that they forged, until one day, they walked away from it after the birth of independent India.

The change in dynamics has been evident ever since and the borders simmer with discontent to this day. Even as Nepal sought to define its democracy, China made its intentions clear when it came to Tibet—a gut-wrenching saga that has unfolded ever since. Douglas meticulously captures the early days of these mountain nations that have determined their present.

Mountaineering too has had an influence on these communities in terms of livelihoods and opportunities, besides exposing them to the developed world. The book traces the early accounts of climbing outside of the Himalayas, which eventually defined how the big mountains were approached by Europeans. However, Douglas skirts around the detailed exploratory accounts in favour of a more objective narrative that provides valuable insights into many landmark climbs. For instance, while the exploration and subsequent first ascent of the Everest have been elaborately documented, he instead explains the circumstances which led to the British staking claim to the mountain and how climbing transformed from an adventure to a nationalist agenda over time. Or how commercial expeditions have changed the way these mountains are climbed today, while also hurting these pristine environments.

Douglas sheds light on a host of fascinating characters from diplomats to rulers to monks to activists. He also shares nuggets on how opium, tea, pashmina and rubber were responsible for a change in fortunes, what it took for the stubborn potato to make itself at home in the hostile mountain environment and the fate of Sherpas and high-altitude climbing.

A mountaineer at heart, Douglas goes beyond the scope of adventure and documents the extensive history of mountain communities, which spans centuries, and diligently curates an account that is both erudite

and engaging.