‘Grief takes many shapes In the novel,’ says Jokha Alharthi

JOKHA ALHARTHI AND the translator Marilyn Booth blazed into the English literary world, in 2019, when they won the Man Booker International prize for Celestial Bodies. The win ticked many firsts, as it was the first time an Arabic-language writer had been awarded the prize, it was also the first novel by an Omani woman to appear in English translation. Celestial Bodies beat the toughest competitor that year, Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Nobel prize-winning Polish author Olga Tokarczuk. For Alharthi the win was a “great honour” that was not just personal, as for nearly 2,000 years, cities like Cairo and Beirut have been seen as the “centre of culture in the Arab world”. The prize was thus an honour for all of the Gulf countries too.

Celestial Bodies tells of fractured relationships and unhappy marriages in an Omani village, as its women protagonists strain against the restraints of patriarchy in an Islamic society. An intergenerational story, it captures the arcs of three sisters, Mayya, Asma, and Khawl. The novel speaks in different voices as each chapter is embodied by a single character. While chronicling the unhappy lives of the three women and their families, readers also witness the evolution of Oman from a slave-owning society to its oil-rich present. The novel was hailed for the “perfection of its form” (The New Yorker) and as “a richly imagined, engaging and poetic insight into a society in transition and into lives previously obscured” (The International Booker prize judges).

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

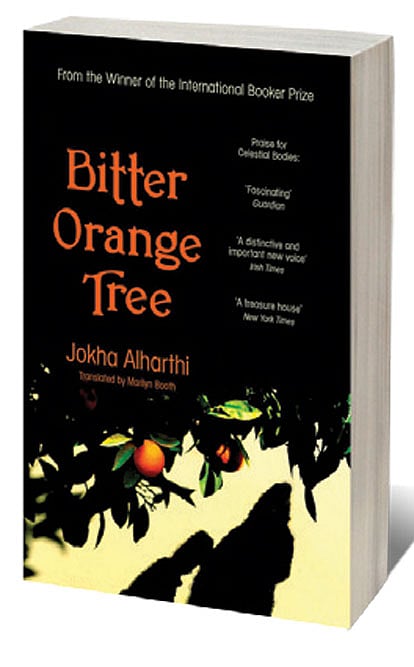

Oman has witnessed immense change in a compressed period of time, and Alharthi’s novels humanise these upheavals. Her second English translation (also by Booth) which released recently, also hints at these changes. Slipping between past and present, dream and reality, this is a novel that examines social status, change and status quo, female agency, and the lack of it. Titled Bitter Orange Tree (Simon & Schuster; 214 pages; ₹699) the novel’s narrator is Zuhour, an Omani student waking up in a snowy UK city. Far away from home she mourns the death of her adopted grandmother. Through Zuhour’s eyes we see her posh Pakistani friends, Suroor, with “jet-black hair rippling down her back and a dazzling smile,” and her sister Kuhl who has recently eloped and married a boy from a village in Pakistan’s boonies. Zuhour gets increasingly invested in this relationship over the course of the novel. Walking through foreign streets, Zuhour constantly sees Bint Aamir, the woman who raised her. Her grandmother never owned anything, but she is the one who planted the trees in the courtyard. The reader travels with Zuhour from the vegan parties at university to the shade of the lemon tree in Oman. It is a novel very much set in the world of gypsy women on one hand, fall colours on the other, and a world where tears turn into pearls. Alharthi’s skill as an author is that she allows all these three worlds to coexist. As she spends time with her friends, Zuhour comes to realise, “For a moment, I imagined myself a part of it. But in reality, I wasn’t part of anything at all.” Zuhour’s search for home makes her realise that her only refuge was, perhaps, her grandmother.

Bitter Orange Tree is a novel about loss (whether of innocence or loved ones), old age and frailties, old age and resilience and the loneliness of grief. The narrator observes, “My grandmother died. The people around me were sympathetic, but no one was prepared to understand me. Sympathy isn’t understanding.” It is also a novel about female relationships, whether it is friendships (Zuhour with Christine, Kuhl and Suroor) maternal bonds, or lack thereof (Zuhour’s mother and her children), nurturing bonds (Bint Aamir and a host of people), sisterhood (Zuhour and her sisters).

Alharthi has a PhD in classical Arabic literature from the University of Edinburgh, UK, and is currently a professor in classical Arabic literature. She speaks of the influences of poetry and the meaning of home and family.

Bitter Orange Tree was first published in Arabic in 2016. As an author, how do you deal with the two births of your book? First in Arabic, and a good six years later in English? Does it feel like two different books coming into the world, and in what ways?

It does feel rather like that, though—of course—a translation is a great gift, and questions arise in the editing of the translation that are very interesting for the author (and hard to anticipate). There are also two different worlds for the novel’s two births: the Arabic-language world, with its particular perception of Oman, and Omani literature; the English-language world, with a very different sense of Arabic-language literature, and Oman as a subcategory of this literature. Time, too, changes any writer’s perception of their work.

Bint Aamir is a particularly interesting character as her lifetime maps many transitions in the country. Women like her—of great strength, resilience and compassion—seem to belong particularly to one generation. What makes them who they are?

Perhaps their own will to define themselves, rather than be defined. Bint Aamir commands respect and admiration, I think, and, ultimately, love, but she is a complex figure for younger generations, who have not lived through, precisely, her mix of experiences. She loves her family and remains an outsider within her family, and this paradox also explains her strength, I think. A woman in India who has lived for 80 years, seen Partition, and everything since, will have a mindset quite different in many ways from her daughters, granddaughters, and so on.

This novel is largely about women and the griefs they carry. Through the novel can you talk a bit about intergenerational grief?

You are right. We grieve differently at different stages in our lives, and we grieve for different things. Bint Aamir can grieve that she remains an outsider in a family within which she is nevertheless the lynchpin. Zuhour is mourning her grandmother but also other losses—perhaps a sense of her own self while she studies in a country that is not her own— and Kuhl and Suroor, two sisters from Pakistan, experience a potential restricted by the expectations of their wealthy parents; they are in some ways burdened by expectations that a far less privileged figure, Bint Aamir, never experienced. So, grief takes many shapes in the novel, and is not exclusively about the death of a person, but their absence in other ways. Zuhour’s sister is nicknamed “The Dynamo”. She is a force of nature, until something happens and she changes, and others are left to mourn the loss of the former person.

Zuhour moves from her home country to study in the UK. In what ways do you think the move away from ‘home’ to a new place, gives her a refreshed perspective?

Zuhour does experience a different perspective in the UK. University is, of course, a multicultural experience in a way that ‘home’ is not, but it is also a place in which identities are being shaped, and Zuhour is perhaps caught between two identities—the person she was before she left home, and the person she is in the process of becoming. These two identities are also the person she was when Bint Aamir was alive, and the person she became afterwards. This is why when Zuhour recalls that Bint Aamir says “Don’t go,” it may feel a little like a betrayal of the past. The refreshed perspective does not necessarily make ideas of home easier. This is true for many characters of the novel.

What are your memories of a bitter orange tree? When and how did you decide to set it as a motif in this novel?

I do not have memories of any specific tree—it simply became, as you say, a motif in this novel. In the novel, Bint Aamir longs to have her own plot of land on which to grow things, including the narinjah/bitter orange tree. Just as the novel is about forms of grief, it is also about fulfilled and unfulfilled potential, and Bint Aamir instead comes to care for the trees and plants and possessions of others. Which comes with its rewards and with its drawbacks.

You grew up immersed in Arabic literature and history. Your uncle and grandfather were poets. Could you describe that life surrounded and infused by books and verse?

It is true that it has influenced me enormously; my PhD is on Arabic love poetry, for example. So, the influence is long-lasting. As a child, I had access to literature easily, yes. But there is also a great interest in and support for poetry nationally, and this poetry is in conversation with broader themes within Arabic literature and history. Poetry unlocks the door in some ways. It is also true, today, that poetry can distil or capture what other literature cannot, and this is an education in itself.

What was it like to grow up in a family of eight sisters and four brothers? How has that made you the author you are today?

I think—as a writer who also teaches, and who also has a family of her own—I learned early to try to manage my time to focus on my own work as well as other things. My sisters became my best friends. I have benefited enormously from their input and advice over many years.

An Indian woman author recently won the Booker International prize. Her award has been one of many firsts, just as yours was three years ago. With the experience and knowledge of the last three years, what advice would you give Geetanjali Shree?

First of all, warm wishes and many congratulations to Geetanjali Shree! I do not think I should offer advice, every author takes their own path! However, my three thoughts are: to enjoy this great moment! To conserve energies, also, for new work—readers will soon ask about it. Finally, to keep in mind one’s role as a fiction author. Sometimes, the world at large has considered me a spokesperson for Oman, which is obviously a very different role!