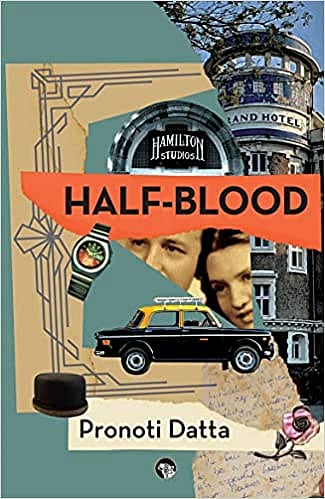

Fractured Lives

If there’s anything that can summarise the principal conflict of journalist Pronoti Datta’s searing debut novel Half-Blood, then it’s this: “Could you know yourself without knowing your past? Look where it got Oedipus.”

In everyday situations, more than we realise, our past beckons us to reconcile with it. It clutches on to us, not letting us be in the moment, making us creatures of in-between times and parallel universes.

Maya, the 34-year-old journalist, an adopted child of an unusual Bengali couple—Mini and Shivaji Deb—and the protagonist of Datta’s novel, is one such in-between existentialist. She is trying to process herself and her behaviour through the journey of knowing her biological father Burjor Elavia.

Burjor, who disappeared after leaving his new-born daughter with one of the many women he had had an affair with, Mini, was born to a Parsi man and a tribal woman. He was, as Parsis say, a “fifty fifty”—an “Adhkachru”. A Casanova, a taxi driver, and a noncommittal lover who wooed women of all ages, Burjor was also an enterprising gent, running shady businesses and taking a cut from people whom he helped. And Armaity, his wife, died shortly after giving birth to Maya.

Certainly, the ones who are absent from our lives make their presence felt in unimaginable ways. Somehow, in each situation, they tend to occupy the central position. Especially those who get left behind, mostly their children, find their lives becoming a mystery—a puzzle they’ve to keep on solving, fixing things, connecting dots, in anticipation of finding ‘meaning’. No matter how much you want to delay this quest as Maya did, eventually, it’s what you come back to.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Maya also did the same when she got tired of trying “plenty of hobbies looking for that one meaningful vocation. Old-fashioned ones like pottery, philately, gardening,” only to begin “looking for Burjor” to find her truth using a letter, along with a few contacts, that Burjor had left.

In telling Maya’s story, Datta’s prose champions Mumbai city, its idiosyncratic people, and their stories with skill. Maybe because of working as a journalist, the sections in which Datta describes a typical newspaper environment, its people looking for upward mobility, and the casual sexism at the workplace, alongside fart jokes, all seem uncannily real.

There are many tools in Datta’s literary arsenal that she uses adroitly, enriching the text by supplying in-between details or musings. Be it the philosophical arguments, invoking Camus, Nietzsche, and Kierkegaard, made by Maya’s teachers that loop through her mind as an adult, or be it the thought that she’s exactly like her father when it comes to meeting people of the opposite sex, “every piece of self-knowledge” in Maya’s life is “accompanied by a major event in Bombay”.

This novel does braid the personal and larger history of a city convincingly. It has a rootedness of its own. If the magical realism keeps one going in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, making it ‘believable’ because of the familiar political events at play, in Half-Blood it’s the day-to-day, the mundane that mesmerises a reader, leaving no room for disconnect.

As a reader, it’s a joy to follow Maya’s progression “from being a rootless individual” to someone who suddenly is privy to a history of her own. The inherited and the historical traits converge for her, forming “a solid kernel implacable in the face of life’s forces.”

Because of its sheer storytelling, not only does Datta’s debut easily occupy a space in the canon of those extraordinarily told ordinary stories, but it also triumphs a virtue that Camus admired—“a will to live without rejecting anything of life”.

Half-Blood doesn’t reject anything; it’s a story of fifty-fifty people, in full.