Flights of Fancy

The uphill hike hadn’t been as exhausting as the search for the elusive Himalayan Monal. Before setting off into the Great Himalayan National Park that lies in the Kullu district of Himachal Pradesh, I had heard enough tales of the naurangi or the nine-coloured pheasant.

The monal is considered royalty in these parts, and hence its difficult relationship with the locals. Though hunting has long been banned and is liable to punishment, its numbers have dwindled over the years. The shining crest of the male monal continues to adorn the Himachali caps worn during melas and wedding celebrations. Its meat is a delicacy in secret circles. As for me, all I wanted was a glimpse of this magnificent bird.

The climb had now taken us over 2,500 metres and well into the idyllic domain of the monal. Any distraction was easy to trace amid the silence. This included my grumbling stomach that grew louder with each passing moment, disgruntled with the piece of chocolate that I offered it time and again. With dusk approaching, we had little choice but to end our search and double march to our camp at Shilt Top in the fading light.

I’m at best an amateur birdwatcher, drawn to the sweet nothings of the twittering on serene mornings and the thrill of the chase, united in spirit with erudite ornithologists, naturalists and researchers, though half as invested in the effort that it demands. The entire delight of spotting birds is an exercise in patience and perseverance. It sets the heart racing and the feet shuffling, while all along trying to maintain stillness. The eyes are glued in anticipation of the prized catch, well aware that at times it could be down to a whole lot of luck. And unlike me, if you are fussy about what you’re out to spot, going home empty-handed is often the norm if your homework isn’t in place.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

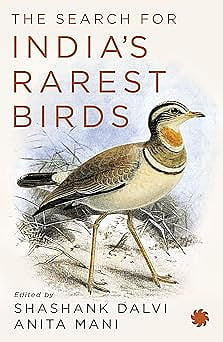

For anyone who has engaged in this compelling pursuit, the encounters from The Search for India’s Rarest Birds will be an enthralling armchair read for a cosy weekend. The book editors, Shashank Dalvi and Anita Mani, have handpicked these intriguing chases from across the country, well aware of what such an endeavour entails through their own experience.

As in all such searches, the rarer the sighting, the dearer the chase. Birds like the Jerdon’s Courser were regularly spotted in the latter half of the 19th century, until it went missing for 86 years. The Forest Owlet hadn’t been seen in over a century. So goes the question for every birder—in the vast landscape of India, could these birds have survived in a few remote pockets?

“We specifically went after the stories of rediscovery, because there’s a lot for anyone to learn through the entire process. It’s more ‘Sherlock-y’ in that sense,” Mani says.

It’s easiest to perceive it as a treasure hunt of sorts, the clues sitting pretty amid museum specimens, academic papers and historical records, the search also entailing the use of more modern tools such as Google Earth, night vision, DNA analysis or the field of bioacoustics today. This is a world of a difference from how similar exercises were conducted in the past, where just accessing far-flung areas was a taxing effort, before even committing long hours to the chase.

While roads today have been carved out in what was once considered treacherous terrain, the same infrastructure development has led to depleted forest cover and dried up wetlands. Alongside climate change, it has pushed a few species up the highest peaks and deep inside jungles.

“While access is easier today, habitats are declining across the country, as are bird numbers. For instance, the Jerdon’s Courser was once considered lost, rediscovered as you read in the book, and then lost again. The last sighting was back in 2009. So, it’s evident that finding certain species is getting really difficult, in spite of the tools we have today,” Dalvi says.

Besides the excitement of spotting and ticking off species on the wish list, there is now a sense of urgency as well. In a country obsessed with tigers and cheetahs, where the elephant and one-horned rhino are often treated as second-class citizens, birds tread a thin line between being rarely spotted and simply going extinct.

“There are birds like the white-bellied heron that I’m desperate to see. Just a handful have been recorded in the northeast, since it has a very specific habitat around fast-flowing rivers which makes it that much harder to spot. And I do hope that this urgency is the trigger for taking conservation issues more seriously in the future,” Mani says.

Local conservation efforts, such as those seen in the northeast, are the way forward according to Mani. Once hunted to cook up a feast, Mr Hume’s Pheasant is today protected by the locals of Jessami and Razai Khullen in Manipur, who in turn have benefitted through birders who regularly visit the area.

“People sitting in towns who intervene from time to time are not part of the landscape and cannot make it work. It can only become sustainable if locals are made a part of the entire process. That’s the most successful kind of conservation strategy which is needed today,” she says.

The book relives the notable work of British naturalists such as Edward Blyth, AO Hume and TC Jerdon, followed by their Indian successors, Salim Ali and Humayun Abdulali. Folks like Dalvi keep their spirit alive through their own exploration and exploits—a field biologist, he was part of a team that discovered the Himalayan Forest Thrush, one of only five new species discovered since India’s independence—while encouraging others to grab their hats, pack the binoculars and set off on a little adventure of their own.

It’s what got me going on the hunt for the monal, but so far, my efforts were futile. Early next morning, I climbed higher to reach the summit of a peak called Rakhundi Top that offered stunning views of the Tirthan Glacier in the distance. The descent down a steep slope was a tricker affair, requiring all my focus and slowing me down considerably. In the next moment, I was startled by a shrill call on my right. A monal set off from the mountain face behind us and drifted across the valley, its gleaming plumage lighting up the surroundings. And my day as well.

Top Birding Destinations Recommended by the Editors

Eagle’s Nest, Arunachal Pradesh

The elevation range is fantastic. If you are a child, it’s like eating a multi-tier cake that never seems to end and there are goodies at every stage. At every twist and turn you see new landscapes and new birds. In fact, one can experience an entire gamut of birds in a single day while driving from Kaziranga National Park (250m) to Sela Pass (4,200m).

Ladakh

The bird density is not great and the number of species is far less, but the landscape and the ability of these birds to survive in those harsh conditions is mind boggling to see.

Delhi

There’s a lot of wetland birding in and around Delhi and this is a great example of how different kinds of birds flock and thrive together. But these are also among the most endangered landscapes in India. Over the last 15 years, entire wetlands have vanished and the drive to access these areas has only increased over time.

Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Western Ghats

These are hotspots for a lot of endemic species such as the Nicobar Megapode and the Banasura Laughingthrush.