Family Ways

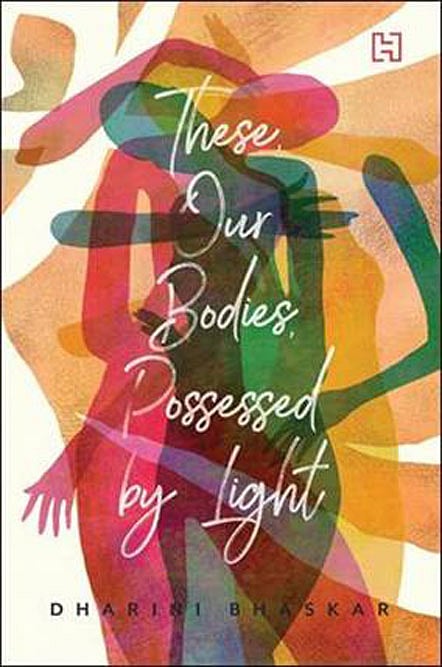

Dharini Bhaskar grapples with love, loss, family, and memory in her debut novel, These, Our Bodies, Possessed by Light. Bhaskar’s prose, rich in imagery and shot through with lyricism, borders on poetry. There is plenty of wordplay to delight in, plenty of well-crafted sentences and startling insights to savour. The novel’s title, a line from the Richard Silken poem, Scheherazade, is an apt fit.

These, Our Bodies, Possessed by Light is Deeya’s story as much as it is her mother’s and grandmother’s. When an affair is set to turn her life upside down, Deeya digs deep into the past in the hope of finding answers for her present dilemma because ‘maybe all of us are no more than Venn diagrams—our personal biographies and those of our relations colliding to create the teardrop of our selves.’ Suspended between her new love and her humdrum marital life, she parses her family’s history, retracing the ‘stories of those closest to her—Mamma, Amamma, Daddy, Ranga, Janaki. Both her Mamma and Amamma (grandmother) have had their trysts with love and neither of the two women have had it easy. Deeya is compelled to excavate their histories since she believes that reminisces and ‘a shared unconsciousness’ are part of her inheritance. The past, which can be both a curse and a comfort, haunts Deeya as much as her uncertain future.

The loves and life of Amamma (Sarojaa) are sensitively sketched. Her adolescent bond with Venu, the boy who waits for her by the school gate with a handful of wildflowers, is fleeting but moving. Venu is the only one who revels in the fact that Sarojaa is not like other girls. He understands she is ‘unabashedly spirited, unabashedly whole’. Sarojaa is married off to an older man, but Venu promises to keep in touch with her. Using her fertile imagination, Deeya conjures up the contents of the letters Venu wrote to Sarojaa after his move from Madras. Venu’s fraught attempts to convey his love for Sarojaa while maintaining the distance expected of him are a delight to read as is Sarojaa’s internal monologue in response to his letters.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

Deeya also spends time and energy on deconstructing her mother’s life story, which is intricately bound to hers in more ways than one. The family is shattered when her father leaves—a shocking decision he makes in Deeya’s childhood. His absence affects Deeya, her mother, and her siblings deeply. Deeya observes her mother’s reactions to his departure/disappearance, often struggling to understand her, while she herself grapples with the blow. As a child, she finds comfort in make-belief, pretending her father has moved to a foreign country and that his absence won’t last forever. When she grows up, she once goes on a ‘pilgrimage’ to Norway in search of her father on a whim. To no one’s surprise, he remains a distant, absent figure throughout.

As the story unravels, Deeya is able to paint a fully fleshed-out portrait of her grandmother, but her mother, a bunch of contradictions, is much harder for her to figure out. There is a delicious irony in this since similarities between the mother and daughter run deep. And so do their differences.

Since the novel is written in the first-person, the fictional world Bhaskar conjures up—and the characters who inhabit it—spring from Deeya’s voice and worldview. While the first-person narration sets readers free from the ‘tyranny of objectivity’, it also tends to get a bit tedious at times. As in life, so in fiction—it’s not easy to stay engaged with a single narrator for 300-odd pages. Some plot points tend to stick out. A few coincidences in the novel place too high a demand on the reader’s capacity for willing suspension of disbelief. But Bhaskar does manage to dexterously meld word with image, sentiment with philosophical insight, timeless myths with modern angst, and tell a deeply personal story with universal echoes.