‘Every Gandhi-sceptic and Gandhi-adherent must bear in mind that he was human’

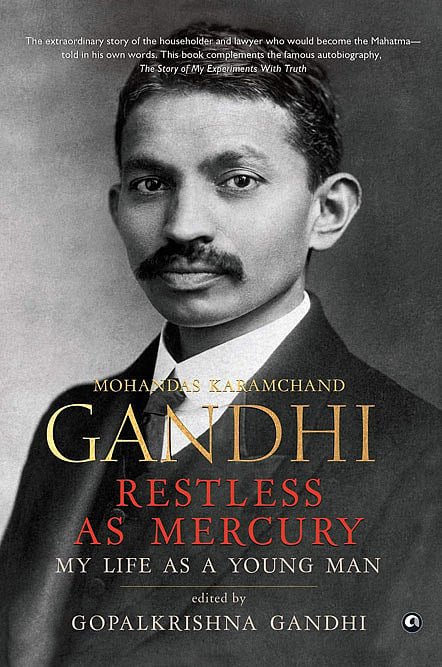

Restless as Mercury is an outcome of Gopalkrishna Gandhi’s extensive research into the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi and books and accounts of him written and recollected by those close to him under his guidance besides An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Which is why Gopalkrishna, an alumnus of St Stephen’s College, writes as if at the behest of Gandhi to fill the gaps of the late leader’s portrait as a young man, mostly from his own recollections. Although Gopalkrishna’s contribution to the making of this book is Herculean, he prefers to be called the editor of the book. The author, paternal grandson of the Mahatma and maternal grandson of C Rajagopalachari, has dedicated this work to Gandhi’s secretary and translator of his autobiography, Mahadev Desai, and offers tributes to six people whom he calls path-finders for most Gandhi biographers: Joseph J. Doke, Millie Graham Polak, Prabhudas Chhaganlal Gandhi, James Hunt, Pyarelal and Enuga S. Reddy.

Edited excerpts from an interview with Gopalkrishna, a former IAS officer who has also held several key administrative and diplomatic posts:

Why did you write this book?

To make the many self-descriptions lying hidden in The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi and elsewhere available to those who find his autobiography, which ends in 1920, to be in need of augmenting.

What Gandhi’s sister Raliyat said of him as a young boy is the title of your book, Restless as Mercury. My immediate thought on reading the title was about the very elevated blood pressure he had suffered in the last decades of his life, that for most others meant hospitalisation or death (220/110 on February 19, 1940; and 194/130 on October 26, 1937, according to an ICMR journal). But Gandhi carried on with his work and had to be killed by someone. What do you think kept him alive and even healthy enough to work, walk and travel tirelessly?

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

A sense of duty, ceaseless, tireless, selfless. And a freedom from two fears – fear of defeat and fear of death.

You interpret Gandhi as saying that he disapproved of his father marrying the fourth time (his mother Putlibai), which he believes was, out of carnal desire. You quote Gandhi as saying in your book, “I have not been able to forgive him for this.” But in Autobiography, Gandhi never speaks about his disapproval or inability to forgive him. Where does this come from? Why does Gandhi associate carnal pleasures for a 40-year-old man with sin that deserves no mercy?

It comes in a later reflection. I should have given the precise reference in a footnote. His ‘inability to forgive’ his father for four serial marriages comes from his absolutist views on what constitutes fidelity, chastity and morality.

How tormented do you think was Harilal who was at the receiving end of his father Gandhi’s excessive obsession with control of earthly pleasures? Do you think Gandhi's dominant character and puritanical views on sex and life had a role to play in Harilal's tragic life?

Only 19 years younger than his parents (Gandhi and Kasturba), Harilal saw his father as ‘work-in-progress’, even as his father saw him as part of his own ‘experiments in truth’. Harilal could not but be a judgmental and critical observer of his father, letting life, rather than his father, shape and mis-shape his days of strife and suffering.

But two things must be remembered by those studying them: First, Harilal was an exemplary satyagrahi in South Africa, leading his father to say he would like every Indian there to emulate his son. Second, when Harilal exited from his parent’s home in Johannesburg he took his father’s photograph with him and when, on January 30, 1948, he heard of his father’s assassination, said (according to a reliable but unauthenticated report) “I will kill the man who has murdered my father”.

Gandhi makes some observations about Malta and Brindisi (that the former was infested with beggars and the latter pimps), two stopovers on those long trips back then to London. He did not write this in Autobiography. Where does this information come from?

From the ‘London Diary’ written by him to assist Indians aspiring to study in England (Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol. 1, p.13).

What do you think are the lessons in life that Gandhi had learnt from his years in South Africa?

In his own words: “The creeper of love O have planted and watered with tears ... And rich has been the harvest”. (p.356 of the book) The lesson he carried away from his years in South Africa was that between communities separated by creed, class and circumstance, there is to be found a commonality of human feelings which alone can enable them to live in peace.

Did the West and Christianity shape him more than India did?

Nothing shaped him as India shaped him, as his mother and father who respected other faith-traditions as much as his own, did. And as his political mentors, the patriots and liberals Naoroji and Gokhale did. It is the same eclectic India that led him to approach the world, including the West (and Christianity), as a learner.

You bring out succinctly how Gandhi in South Africa was a victim of the Europeans, the locals and the minority Asians. Ironically, the Europeans are now appreciative of his ideals and values. But he has now become a villain and a whipping boy for a section of Indians and Africans for his reported racism. Similar allegations are hurled at him for his views on caste and his respect for the varna system. Do you think Gandhi in his later years changed his views on race and caste (especially after debates with Ambedkar)? Or is it true that there was much to be desired in his understanding of caste discrimination and that he refused to think beyond racism suffered by Indians? Even in his conversations with Sree Narayana Guru, Gandhi was seen as supporting the varna system. Are these his handicaps?

Every Gandhi-sceptic and every Gandhi-adherent must bear in mind three irrefutable truths: 1. He was as human as anyone else and therefore as fallible. 2. He never claimed to be otherwise. 3. He was ever wanting to learn and self-correct if convinced of his error. His views on South Africa’s African population’s rights and on varna evolved with time and are there for anyone to ascertain. But there is no denying that as they stand in their original form, they jar. His statements like anybody else’s have to be read in the context of the times when they were made.

Gandhiji had many opponents in politics inside and outside of the freedom movement. Why is that a series of organised assassination attempts were made on his life by hardline Hindutva practitioners alone?

This question would be best answered by those who planned and executed those attempts.

Do you think Gandhi the intellectual was overshadowed by Gandhi the politician?

He was intellectual, he was political. He was a barrister of uncommon skill drafting legal documents both to confront and negotiate with authorities, a soldier donning combat uniform in South Africa, a journalist, an organiser of disciplined mass movements, a deft artisan, cobbler, tailor, farmer and weaver, nature-cure practitioner, dietician and an authority on prison-life. But over-arching all that he was a lover of humanity who was also aware of its suicidal weaknesses and determined to make his love scorch with truth those weaknesses.

What do you think is the biggest highlight of Gandhi's writings, in all the three languages he wrote?

Complete freedom from a desire to impress and clear, direct and un-embroidered communication of what in his eyes is true was the aim of his writing.

How much of his personality was shaped by his family background of being strict ministers for local kings?

His father’s and his grandfather’s integrity, truth-telling and courage were hugely determining influences on him.

Could you please elaborate on Gandhi's views on sister Nivedita which you mention in the book?

He admired ‘her flowing love of Hinduism’ (his phrase). But I wish he had given a more complete pen-picture of what he thought of her personality and its impact on Hindu society.

You always call him MK Gandhi, not the Mahatma. Is it a mere coincidence or is there something to it than what meets the eye?

I find the way he describes himself – ‘Mo Ka Gandhi’ in Gujarati and Hindi and ‘M K Gandhi’ in English (and ‘Bapu’) – nearer the truth of his life as an individual than ‘Mahatma’ which reflects the love and trust of those who addressed him as such.

(Gopalkrishna Gandhi’s latest book, Restless as Mercury: My Life as a Young Man, published by Aleph, hit the stands in early January)