Erotic Forever

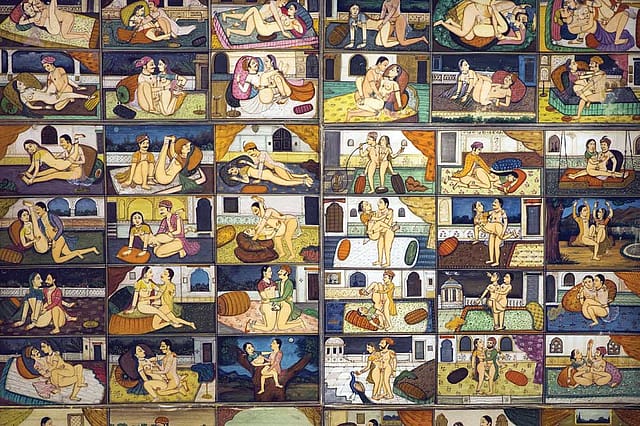

TO READ CENTURIES of voices writing on the erotic is to become keenly aware of a deep argument that exists in the geography of the subcontinent, an argument between literary romantics—who embrace the erotic for the gloss it adds to life—and religious traditionalists— who caution against the erotic, for its disorderly nature and potential to cause chaos. While romantic and traditionalist voices are unanimous in their belief that the erotic holds an extraordinary power and attraction for human beings, each does something very different with that belief. Romantics are erotically positive: they believe life is made worthwhile by its erotic aspects, that the best life is one in which our understanding and awareness of the erotic are maximally enhanced. Traditionalists, on the other hand, are erotically anxious: they believe that a worthwhile life is one in which the four goals of life are in balance; they do not favour the promotion of the erotic, worrying that if not tightly controlled, the erotic could undermine the other three goals of life. Aficionados of the romantic project used the arts as a vehicle of articulation; their literature, music, drama, even grammar, was thought to be imbued with the erotic and capable of enhancing our understanding of the erotic. Traditionalists used both religious writing and the social contract to articulate the dangers of the erotic, believing that the erotic must be kept on the sidelines, aside from its necessary use as a vehicle for reproduction. Romantics believe that coupling is a central life force, and they appreciate the energy that comes from all couplings, whether man-woman, woman-woman, men who identify as women (and are fantasizing about male gods), or (wo)men with God. Traditionalists believe in the notion of an 'ideal couple': heterosexually and monogamously married, with children and extended family in the foreground and a willingness and ability to keep the erotic in the background.

To further understand the argument between traditionalists and romantics, consider a brief history of the time that traditionalism and romanticism have held sway. If we are to start from about 1000 BCE in ancient India, for the first 800 years or so of this time period, that is, beginning with the Vedas, traditionalist sentiments prevail. During this time, the destabilizing dangers of the erotic are far better articulated in the literature than are its pleasures. From the Vedas onwards, traditionalist literature, which is largely in the form of religious texts, is squarely articulate on the need to manage the destablizing potential of the erotic. Beginning in 200 BCE, however, and continuing for several centuries, literary voices sang the glories of the erotic and their dedication to it—in Tamil, Sanskrit, and Maharashtrian Prakrit. From the second to the sixth century, an Indian literary-erotic-nature idiom was spelt out from Tamil Nadu to Maharashtra and up to Madhya Pradesh. Here the poets embraced the erotic along with its problems, accepting that though the erotic often brought anger, grief and shame, it was still worth embracing for its pleasures. During this medieval period emerged the Tamil Sangam poets and the Maharashtrian Prakrit Gatha Saptasati, the prose and poetry of Kalidasa and Bhartrihari, as well as the Kama Sutra itself. After this golden age of the Romantics, puritanism once again holds sway and the next major erotic work—at least the one that has survived—is the collection of romantic poems known as the Amarusataka, written in Sanskrit in the seventh or eighth century and attributed to King Amaru of Kashmir. From the eighth century onwards there is again a long period in which very few important works have survived, the next set being from the Bhakti poets who compose discontinuously from the ninth to the fifteenth centuries in praise of erotic love with God himself. The fact that Bhakti poets praise erotic love only in language that involves a deity suggests that this was considered the most elegant and refined expression of romanticism at that time. Alternatively, perhaps, the social climate—which by this time included both Hindu and Muslim puritans—did not support an articulation of a more explicit person-to-person erotic love. The taboos on self-expression of erotic love might have impinged particularly on women poets and the re-direction of this love to the divine might have spared them the censorship that might have otherwise been forthcoming. Another way of thinking about it is that, dispirited with the limitations of romantic love between humans, some of these poets were able to find a more elevated idiom with the gods.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Following the Bhakti period, the proliferation of the Urdu language and the culture of refinement associated with Islamic courtly love played an important pro-romantic influence; but as the Hindu and Muslim puritans were joined by the British puritans in the seventeenth century, one has the sense that romanticism was very much in the dark ages. Nevertheless, important works continued to emerge in a more scattered fashion. Amongst these individual works are those written by courtesans, such as the Telugu Radhika Santawanam (The Appeasement of Radhika) by Muddupalani, in the eighteenth century. Another is the erotic proponent of the Lucknow school of poetry, Qalandar Bakhsh Jur'at, known for his bawdy yet spiritual imaginings of women in sexual union. As the reader advances towards and past the twentieth century, individual writers offer an exploration of contemporary erotic problems alternating with the past. Contemporary Indian writers who match and build on the efforts of their ancestors write in, among other languages, English, Tamil and Malayalam, and continue to shed profound light on the erotic. …A few of the contemporary writers who have made a searing commentary on the relationship between kama and society include Perumal Murugan, Kamala Das; those whose reverential treatment of the erotic couple recalls the glorious medieval period: Pritish Nandy, K. Satchidanandan, Tarun Tejpal; writers like Manto and Ambai whose erotic-nostalgic writings make us feel lustful and tender at once; modern Bhakti poets like Arundhathi Subramaniam and Kala Krishnan Ramesh; and those who have treated in great depth the extraordinary conflicts that the erotic poses for an individual life: found in the works of Mridula Garg, Deepti Kapoor and Ginu Kamani….

Kama Lives (And we should consider resurrecting daily)

If pleasure is that which makes life liveable, then Kama, as a god of pleasure, might have been invented to allow people to worship the notion of erotic gloss. The most popular story of Kama, of course, involves his death—our classic Indian traditionalist nod to the dangers of erotic life. Kama is killed for being a nuisance, but nonetheless resurrected, as if to say: though a nuisance, the erotic should be allowed to flourish—an idea that the modern reader might find herself agreeing with…

Because the traditionalist and romantic positions are and always have been in argument, the modern-day reader may think of Kama as perhaps less a god than a symbol for the Indian romantic movement, a symbol who is alternately honoured, captured and burned, but eventually left alone as a delightful nuisance. In erotic literature, Kama is also a fictional companion for the romantic, a deity who provides reassurance—as with the invention of any god—that we are not alone in our erotic forays…

The presence, named or unnamed, of Kama as shorthand for the erotic-as-nuisance, as an inevitable companion, and as an essential way of making life beautiful, is one of the continuous threads in this anthology. Traditionalists in the pre-Common Era writings on the erotic may remember Kama for his dangers, for the story in which he is burned to death; however, from the Common Era onwards, we see the romantic movement focus on Kama's survival through representations of desire and its seasons in the natural world. From the argument between traditionalists and romantics comes a dialectic about Kama: 'though he is dangerous and unruly, let us spare Kama, for erotic gloss enhances life'.

In Defence of Nature

Perhaps as a way of circumventing the argument, or as an argument itself, the Indian romantic movement is characterized by nature as evocative of human sensuality. The natural world, the poets seem to say, is writ large with potential for humans in an erotic frame of mind. From 200 BCE onwards the first major wave of pro-erotic poetry, in what would be called the medieval period, appear in what is arguably the world's first group of romantic poets: the writings of the Tamil Sangam poets and the Maharashtrian Prakrit writers of the Gatha Saptasati who make a sweeping curtsey to nature as a part of desire.

Pre-dating the romantic movement in Europe by thousands of years, these poets imagine life—and a lifestyle—with nature and the erotic at its centre. We do not find here echoes of the didactic tone of the European Romantics ('Let Nature Be Your Teacher') nor the wistfulness of the American Romantics ('I Think That I Shall Never See a Poem Lovely as a Tree'). The voices of India's romantic nature poets are unique in a unified perspective of humans and nature. Desire is enhanced and celebrated as a shared geography of (wo)man and nature, a microcosmos to a macrocosmos. This is accomplished via the extensive and at times codified use of nature metaphors: in the Tamil Sangam poems, sprinkled throughout this anthology, each erotic mood is associated with a different landscape. For example, mountains are associated with lovers' quarrels and wives' irritability (ku- unji) and the ocean with long separations (neidal).

The nature metaphors, arising concurrently with the celebration of the erotic in the Indian subcontinent during the several centuries of the medieval period, present the modern reader with both an aesthetic and a problem. Aesthetically, we might look—as our romantic ancestors did—towards nature for giving meaning to the seasonal nature of erotic love: the nuanced and fluctuating nature of erotic love was defended in the ancient romantic literature by nature references. But in the current Indian urban landscape that rushes away from rather than bends towards nature, we might wonder about nature's impact on our relationship with our own and our lovers' bodies…

If we were to read the medieval romantics for a lesson, it would perhaps be: 'Stay erotic, stay close to nature'. In the Kama Sutra's 'Lifestyle of the Man-About-Town'—which would today apply equally to the woman-about-town—the person interested in a life of sexual pleasure must choose a home 'in a house near water, with an orchard' and keep around the bedroom 'oils and garlands…a pot of beeswax, a vial of perfume, some bark from lemon tree and betel'. Likewise, teaching parrots and mynah birds to talk, arranging flowers, cooking soup and preparing wines are some of the nature-oriented activities suggested to put men and women in the mood for sex. The chief protagonists of the Kama Sutra, the Courtesan-de-Luxe and the Man-About-Town are schooled for a life of sex and sensuality, engaging in the kind of lifestyle and activities that in today's urban landscape are available at best on vacation, to the wealthy, an India of heritage hotels that is enjoyed by the privileged and performed by hired help.

Yet desire continues even as the natural ecology disappears. Kama, after all, is infinitely resurrectable. As a counterpoint to Kalidasa, consider the searingly hot, dry, air-conditioned, hyper- urban, trafficked-up twenty-first- century Delhi that forms the backdrop to Deepti Kapoor's A Bad Character. Infused with a kind of emptiness that seems to characterize the modern urban Indian landscape, the city and the sex seem to share something in common, and what appears to have been lost in the natural world has been gained in good whisky.

(This is an edited excerpt from The Parrots of Desire, 3,000 years of Indian Erotica | Edited by Amrita Narayanan | Aleph | Rs 599 | 304 pages)