Equally Ever After

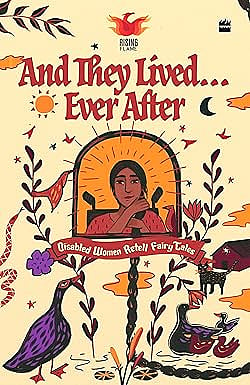

Disability or disfiguring as a trope—for instance, Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve’s prince transmogrified into a beast, or Hans Christen Andersen’s mermaid who becomes mute in exchange for being able to have legs and be on land—is a familiar one in European fairytales. To have a disability in these stories is usually—if not penance, punishment or symbolic of an evil nature—to be in a side role. But in And They Lived... Ever After, an anthology featuring 13 Indian and Sri Lankan women writers, disabled protagonists are creatively and beautifully centred.

The word “happily”, the descriptor on which all fairytales traditionally end, is prominently dropped from the anthology’s title, and this can be understood as an assertion of the right to exist despite life’s complexities or challenges. The characters in these retellings exist in contemporary as well as archaic timelines, are cherished or neglected, are princesses or schoolchildren. Some are born with their disabilities, others become disabled later—through accidents, ailments and even violence.

Andersen’s ugly duckling makes four appearances, and while the obvious parallel of being a misfit in a space that only acknowledges alikeness can be drawn, each writer who works with this story offers her own rendering. Priyangee Guha’s cygnet opens the collection and is on the autistic spectrum, as indicated through stims and echolalia—thus reducing the focus on appearance, on which the judgement and discrimination in this story are classically predicated on. There are a few Rapunzels too, including one who memorably uses her hair to cover her sentient earpiece narrator in Parita Dholakia’s ‘Beat Matching Beethoven’.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Villains—the witches and stepmothers who populate a vast number of fairytale versions—are treated with nuance in several of the stories. In Soumita Basu’s ‘Rapunzel and the People of Companara’, the captor Mama L. turns out to be someone shunned by society. Somrita Urni Ganguly’s ‘Cinderella’s Sister’ makes a series of interesting and compassionate subversions about those with oppressor status. Sharmila Rathee’s ‘The Witch’, the last story in the book, ends on a problematically trite note about maternal love, but the titular archetype is reclaimed as a woman who stands up to the abuse of political power.

Darker stories, true to all fairytale traditions and indeed to life beyond fiction, also have their place. Sarani’s ‘Red’ deals with sexual assault and doesn’t seek a redemptive narrative arc, and Sanchita Ain’s ‘Maryam and the Moon Angel’, which reveals its surprising fairytale link only midway through, is a quietly moving story about ordinary realities.

There is nothing contrived about this anthology: it doesn’t strive to be uplifting, it doesn’t place cause over quality, and it isn’t beleaguered by self-importance despite being what it is—a groundbreaking work at the intersection of disability, feminism and literature, with equal potential to engage directly with the disabled reader or listener, while also enlightening the abled one.

“We would have been on time if the gatekeeper had not delayed us,” says a character in ‘Agal’, P Karkuzhali’s Rumpelstiltskin reimagining set in medieval Tamilagam. The line rings true for the spirit of this unique book that expands South Asian perception and conversation about disabled people and their lives.

And They Lived... Ever After is the outcome of a programme by Rising Flame, an Indian non-profit that takes a feminist and equity-oriented approach to disability advocacy. The programme was a five-month online writing workshop by Aditi Rao, and the stories were edited by Richa Kaul Padte. The book is credited to an organisation because it is a team effort, as well as community-building one in its sensibility. It is made by people who not only live with disabilities and/or chronic illnesses, but who strive to change the way the world understands these—and to make that world more inclusive. Still, the book carries all its significance with a notable lightness, and there is ultimately a sense of felicity to this collection, even if its title suggests tenacity, not triumph.